The

2023

PLAY

BOOK

What’s in store

What steps to take

By Russell Pearlman | Illustrated by Tim Ames

The Problem

Every year creates new challenges, but 2023 will throw a combination of issues (inflation, ESG, labor shortages) at firm leaders.

WHY IT MATTERS

Stakeholders were patient with firms struggling during the pandemic, but are punishing them in the markets now.

THE SOLUTION

Experts say leaders need to develop and stick to a strong strategic playbook for the year.

If there was one wish that most leaders had over the last three years it was for a return to normal conditions. After all, leaders have decades of history, experience, and playbooks to help them handle “normal” conditions, whether good or bad. Sure, the economy is gloomy. But recessions have come along often enough that leaders know how to restructure organizations to manage through them. Yes, there have been labor shortages before, and leaders have overcome those as well. And finally, they have dealt with inflation before.

Read the full magazine

But what if all these “normal” challenges happened—and intensified—at once? Experts worry that’s precisely what will happen in 2023. There won’t be a worldwide shutdown and safety threats like 2020. No more supply-chain snarls, snapbacks in demand, or the Great Resignation either. But for the coming year, leaders have to handle a mountain of issues at once: a rapidly slowing economy, high inflation, investors demanding bigger commitments to environmental and social efforts, and employees still demanding high salaries and working at home. “It’s a post-pandemic unwind,” says Morgan Stanley analyst Ravi Shanker.

What’s more, many of these challenges have turned into the most extreme versions of problems leaders have encountered in the past. Take the macroenvironment. The last time the United States had an annual inflation rate above 8 percent was 1982, a time when most of today’s leaders were early in their careers, still in school, or not even born. That was also the last time the Federal Reserve was willing to push the economy into a recession in order to quash one. But back then, unemployment was around 10 percent, not under 4% as it is now. Corporate profit margins weren’t sky-high the way they are now, either. And there weren’t many stockholders threatening to withhold investing unless companies cut their carbon footprints. “I’ve never seen anything like this, and I’ve been working with leaders for over three decades,” says Jane Edison Stevenson, global leader of Korn Ferry’s CEO Succession practice.

Experts say leaders will need to clearly define their strategy and strictly follow it to get through all of this successfully. In doing so, some will try to go back to how things were pre-pandemic. Others will want to continue pushing in the new directions that have opened up over the last three years. Whatever others may decide, the best leaders will begin designing answers to the massive questions of the day—how many people to hire (or fire), how much to pay employees, how to prioritize commitments to ESG and diversity efforts, and perhaps most critically, how to lead in 2023.

PAY

For all the talk of how much the price of energy and other commodities stings, what really impacts corporate bottom lines is the size of paychecks employees get. An organization spends as much as 60 to 80 percent of its gross revenue on employee compensation, depending on the industry.

And every industry has been spending more on people recently. After not growing by more than 4 percent a year for the entire 21st century, wages in the US rose by 5.4 percent in 2021 and likely grew about the same amount in 2022 as well. Those recent numbers mask the fact that some firms had to boost salaries by 50 percent or more to attract or retain talent. Hamburger flippers, data scientists, and seemingly anyone else who asked their boss for a raise got one, and if they didn’t, they could easily find another employer eager to give them one.

That is likely to change in 2023. The softening economy likely means leaders won’t have to dole out such high raises in the coming year, and some places might not hand out across-the-board increases at all. Indeed, in a Korn Ferry survey this fall of more than 100 retail firms, 51 percent had no plans to offer additional compensation in light of inflation, while another 53 percent had not had any discussions about merit raises next year.

This year, experts say, leaders rely on targeted one-off bonuses, equity grants, or incentives to keep their key talent. Even in a recession, companies probably will find themselves short of people in critical roles. “Faced with continuing record inflation, there will be pressure to accelerate base salaries. But the possibility of economic recession will likely cause leaders to take a more conservative approach that emphasizes variable pay elements,” says Don Lowman, a Korn Ferry senior client partner and leader of its Global Total Rewards business. Another reason to give out incentives for staying: no one knows how long this economic rough patch could last. If, for instance, the war in Eastern Europe ends and inflation recedes, companies could once again find themselves inundated with demand for their products and services—but lacking enough workers to take advantage of it.

The other big issue in 2023 might just be pay equity. During the last 18 months, many companies stretched their salary guidelines. But over time, some employees discovered they were making far less than new hires. This has created some headaches for managers, especially if it looks like firms handed out raises to one group of people but not another. The best way forward, experts say, is to create more robust principles around compensation management, such as hiring guidelines, promotions, hiring and retention bonuses, and counteroffers.

Return to office

Begrudgingly or not, employees are going back to their old stomping grounds—the office. According to Kastle Systems, which monitors card swipes in office buildings, office occupancy has edged over the 50 percent level in many of the biggest markets in the country, the highest since the 2020 lockdowns, with some cities seeing rates of 60-plus percent. Still, those averages might understate the vast number of empty cubicles and conference rooms. Nearly half of companies are currently utilizing only half (or less) of their available office space, according to a recent survey from office-management software firm Robin.

Clearly, employees and their leaders just don’t see eye to eye on the subject, says Jared Spataro, corporate vice president for modern work at Microsoft. In its 2022 Work Trend Index report, the giant software firm found that 81 percent of workers said they are as productive, or more, compared with 2021, but 54 percent of business leaders surveyed feared productivity had been negatively impacted since the shift to remote and hybrid work. And that’s not the only dividing point. After seeing how much money their firms have been saving on real estate and travel expenses, many chief financial officers are advocating for more hybrid scheduling. They see how many office-space leases are expiring (more than 200 million feet worth in 2023, a massive jump from pre-pandemic) and want to make those savings permanent. At the same time, many human resources executives are advocating for more wholesale return-to-office plans as a way to create a more cohesive corporate culture and, the executives hope, increase employee engagement.

Experts say it’s high time that leaders make some final decisions. Leaders certainly

have heard the merits and drawbacks of a full return to the office, and have had

their ears talked off about the pros and cons of flexible scheduling, too.

But by constantly revising policies or putting off decisions, return-to-

office has become a massive distraction, says Dan Kaplan,

a Korn Ferry senior client partner.

One way to help make the decision: ask employees. “Employees all around the world are redefining what we’re calling their ‘worth it’ equation—that is, what they want from work and what they’re willing to give up in return,” Spataro says. Indeed, in one 2021 survey, nearly 50 percent of US workers say they would take up to a 5 percent pay cut to continue to work remotely at least part-time post-pandemic. That figure will vary widely from organization to organization, which is why leaders should figure out what their own employees really want when it comes to hybrid work, as well as what, if anything, they’re willing to trade for it. “Particularly for Generation Z and younger millennials, there are things intrinsically important to them, like how a company lives its values, but may not show up in how they are getting paid,” Lowman says.

Hiring

For most of the last two years, the majority of organizations couldn’t hire people fast enough. But starting over the summer, some began tapping the brakes on hiring. In a survey of its biggest clients, Korn Ferry found that 20 percent put in place hiring freezes of some form in 2022. Many organizations have become reluctant to spend on mid- and senior-level positions unless absolutely necessary. Other organizations, having found that they overhired in 2021 and early 2022, started laying a few people off.

Depending on who you listen to, a recession is either already here or arriving very soon. Unemployment, now at under 4 percent, could peak above 5 percent over the next year and a half, says Leslie Preston, senior economist at TD Economics, part of TD Bank. At a minimum, an economic downturn might restore some of the leverage employers lost during the Great Resignation. What this means, experts say, is that employers can make adjustments to their hiring offers without worrying unduly that potential employees will walk away. The era of 50 percent raises to get people to jump ship may be over, and things like flexible scheduling and full-time remote work are moving from automatic yeses to benefits that are negotiated, or even earned.

However, companies may not want to be too hasty in laying people off. For one thing, employees might do the work for them. The number of people quitting jobs has been sky-high over the last two years and would have to fall drastically to get back to historic norms, an unlikely scenario unless there is a full-blown depression. If a company loses 10 percent of its business in 2023 because of an economic downturn, 10 percent of the workforce might still quit. “Companies should model their workforce needs at different levels, and remain attuned to the demand side of their business,” says Doug Charles, president of Korn Ferry’s Americas region.

At the same time, a recession might not last particularly long or be particularly painful. Leaders do not want to repeat what happened in the fall of 2020, when the economy snapped back after COVID-19 lockdowns and a lack of employees forced them to leave revenue on the table. In the interim, corporate profit margins are at or near all-time highs. “Most companies are enjoying exceptional profitability. Hunkering down is a mistake for them,” says Nathan Blain, global lead of Korn Ferry’s Optimizing People Costs practice.

“I’ve never seen anything like this, and I’ve been working with leaders

for over three decades.”

esg

It’s the acronym that may come to define organizations in the 2020s. The last three years have seen an overwhelming amount of money—an estimated $2.5 trillion globally—earmarked by firms to make production facilities more energy efficient, offsetting carbon emissions, attracting more leaders from underrepresented groups, or embarking on other projects that improve the environment or general society.

An economic decline, however, will likely force some leaders to make tough choices. Without prioritizing projects, both leaders and employees could become frustrated. Leaders should be encouraging their employees to make business cases for their ESG projects. In a recession, a project marketed as “the right thing to do” will lose out to projects that can enhance long-term revenue or reduce long-term costs. And if they haven’t already, leaders should be developing an overarching sustainability strategy, one that commits the firm to making operations more efficient, reduces waste, and creates more resilient supply chains.

An economic decline, however, will likely force some leaders to make tough choices. Without prioritizing projects, both leaders and employees could become frustrated. Leaders should be encouraging their employees to make business cases for their ESG projects.

In a recession, a project marketed as “the right thing to do” will lose out to projects that can enhance long-term revenue or reduce long-term costs. And if they haven’t already, leaders should be developing an overarching sustainability strategy, one that commits the firm to making operations more efficient, reduces waste, and creates more resilient supply chains.

If leaders think an economic downturn will lessen the pressure to continue those projects, they are mistaken, experts say. For one thing, a recession probably won’t depress long-term demand for more energy-efficient products and services. On the social front, numerous studies have shown how adding diversity throughout an organization often leads to better decision-making, more innovative products, and higher profits. “Addressing ESG is about future-proofing your business, even more so in tougher economies,” says Victoria Baxter, senior client partner in Korn Ferry’s ESG & Sustainability Solutions practice. If clients and investors don’t demand more action, governments likely will. In Europe, for instance, governments are going to start taxing certain industries and products that don’t reduce their carbon footprints. In India, new environmental rules will require companies to submit detailed emissions data starting in 2023. And in the United States, experts believe it’s only a matter of time before securities regulators create mandatory climate-reporting standards.

Leadership

Despite the combined challenges of inflation, a recession, a war, and a lingering pandemic, some leaders will be tempted to try to pick up all the initiatives and strategies they dropped off when the pandemic struck. That could be a sound strategy, experts say, depending on the situation; but leaders need to consider whether it’s viable. Korn Ferry’s Jane Edison Stevenson likens it to making detailed plans to renovate a house, then not living in it for three years. “What you planned was brand-new, but now it might either be out of date or might not work,” she says.

Deciding on the company’s direction will require some reflection, Stevenson says. The best leaders will carve out time for themselves and their top executives to create opportunities in their days to think. It’s not about taking a month off, Stevenson says; it’s about devoting mental energy to strategic thinking. “Schedule time to think and plan, or you will just thrash,” she says. Once they decide which way to go, leaders need to focus—both themselves and their employees—on top business priorities. Leaders also need to protect their employees from the “noise,” from stock-market swings, news of problems at other firms, and other world events. “With so much happening, it’s too easy to become spread thin and lose sight of what is essential to keep your business moving forward,” says Elizabeth Freedman, a leadership coach and author of Work 101: Learning The Ropes of the Workplace Without Hanging Yourself.

“Most companies

are enjoying exceptional profitability. Hunkering down is a mistake

for them.”

That focus is necessary because 2023 could wind up being a make-or-break year for many top leaders. During the worst parts of the pandemic, companies lost billions and many stock prices sank, but investor groups felt they couldn’t

blame the corner office for a once-in-a-generation occurrence. Such empathy, experts say, runs out

during economic downturns. Leaders can no longer

use COVID-19 and its corresponding knock-on

effects to excuse poor performance. CEO turnover

went up 8 percent over 2021, and experts believe

it will rise even further this year. “You definitely

won’t get a pass in 2023,” Blain says.

The Tide

Is Turning

In 2023, the biggest challenges leaders could face are managing a

slower growing economy with fewer employees...and keeping their jobs.

3.6% rate was lowest since Dec. 1969

US fully regains the 25 million jobs

lost during pandemic

COVID-related

lockdowns begin in

US

Unemployment rate

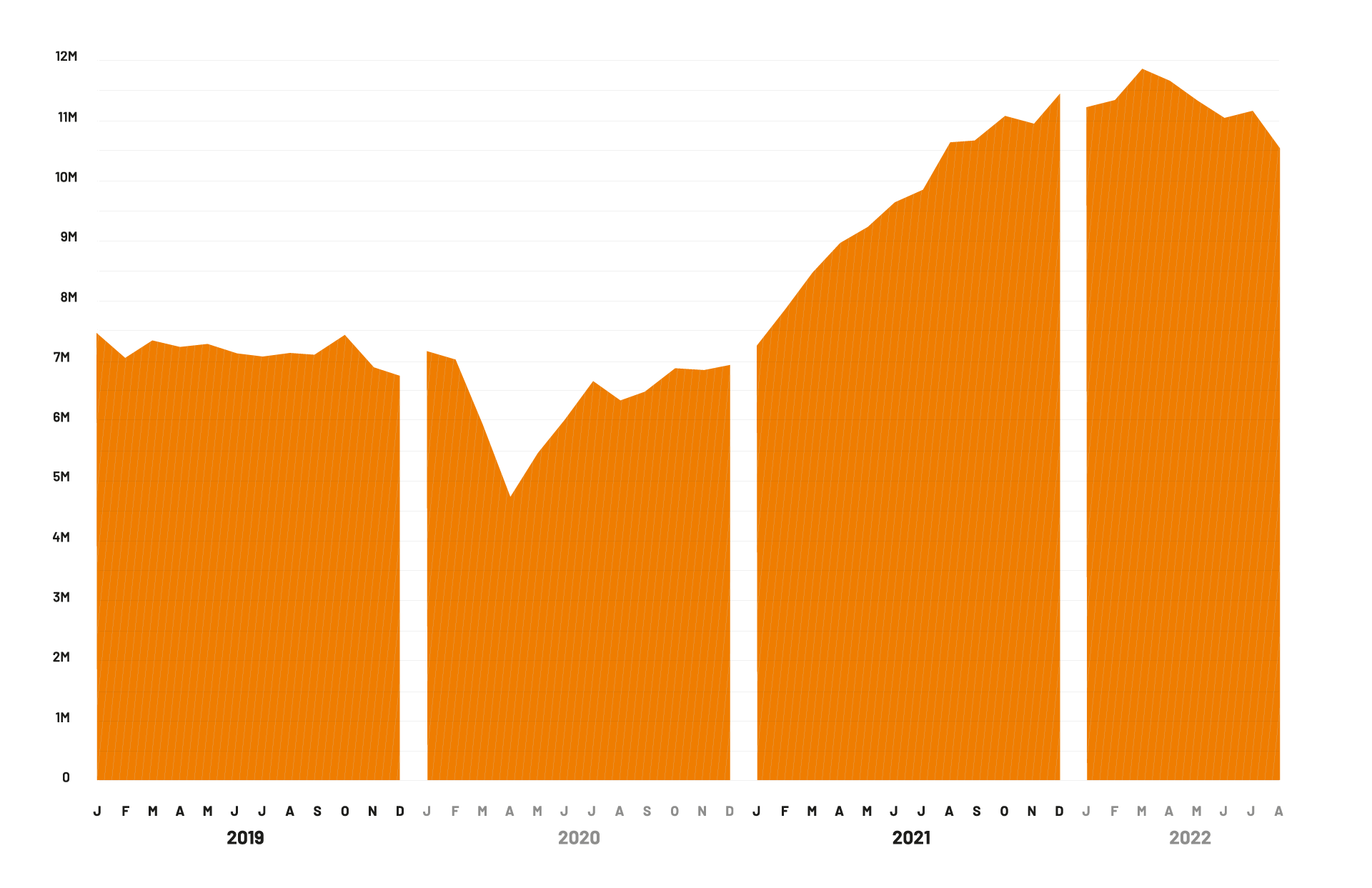

Job openings

7.6 million open jobs posted, highest since first tracked

in 2000

4.7 million, the lowest number of open jobs during the pandemic

More than

47 million people quit their jobs in 2021, a record

There were nearly 2 open jobs for every unemployed American, a record high

Return to work

Many leaders had hoped to reopen offices around this

time

Vaccines

are readily available for US adults

In some cities

in the South, return-to-office rates were already at 50% or higher

A new COVID surge sent many people who had returned to the office back home

CEO Turnover

Many firms

were leery of making CEO switches during the worst of the pandemic, but less so as the global economy weakened.

READ THE

FULL MAGAZINE

READ THE

FULL MAGAZINE

An economic decline, however, will likely force some leaders to make tough choices. Without prioritizing projects, both leaders and employees could become frustrated. Leaders should be encouraging their employees to make business cases for their ESG projects. In a recession, a project marketed as “the right thing to do” will lose out to projects that can enhance long-term revenue or reduce long-term costs. And if they haven’t already, leaders should be developing an overarching sustainability strategy, one that commits the firm to making operations more efficient, reduces waste, and creates more resilient supply chains.

If leaders think an economic downturn will lessen the pressure to continue those projects, they are mistaken, experts say. For one thing, a recession probably won’t depress long-term demand for more energy-efficient products and services. On the social front, numerous studies have shown how adding diversity throughout an organization often leads to better decision-making, more innovative products, and higher profits. “Addressing ESG is about future-proofing your business, even more so in tougher economies,” says Victoria Baxter, senior client partner in Korn Ferry’s ESG & Sustainability Solutions practice. If clients and investors don’t demand more action, governments likely will. In Europe, for instance, governments are going to start taxing certain industries and products that don’t reduce their carbon footprints. In India, new environmental rules will require companies to submit detailed emissions data starting in 2023. And in the United States, experts believe it’s only a matter of time before securities regulators create mandatory climate-reporting standards.