table of contents

close

TRY BET+ FOR FREE

Stream exclusive originals

table of contents

Close

TRY BET+ FOR FREE

Stream exclusive originals

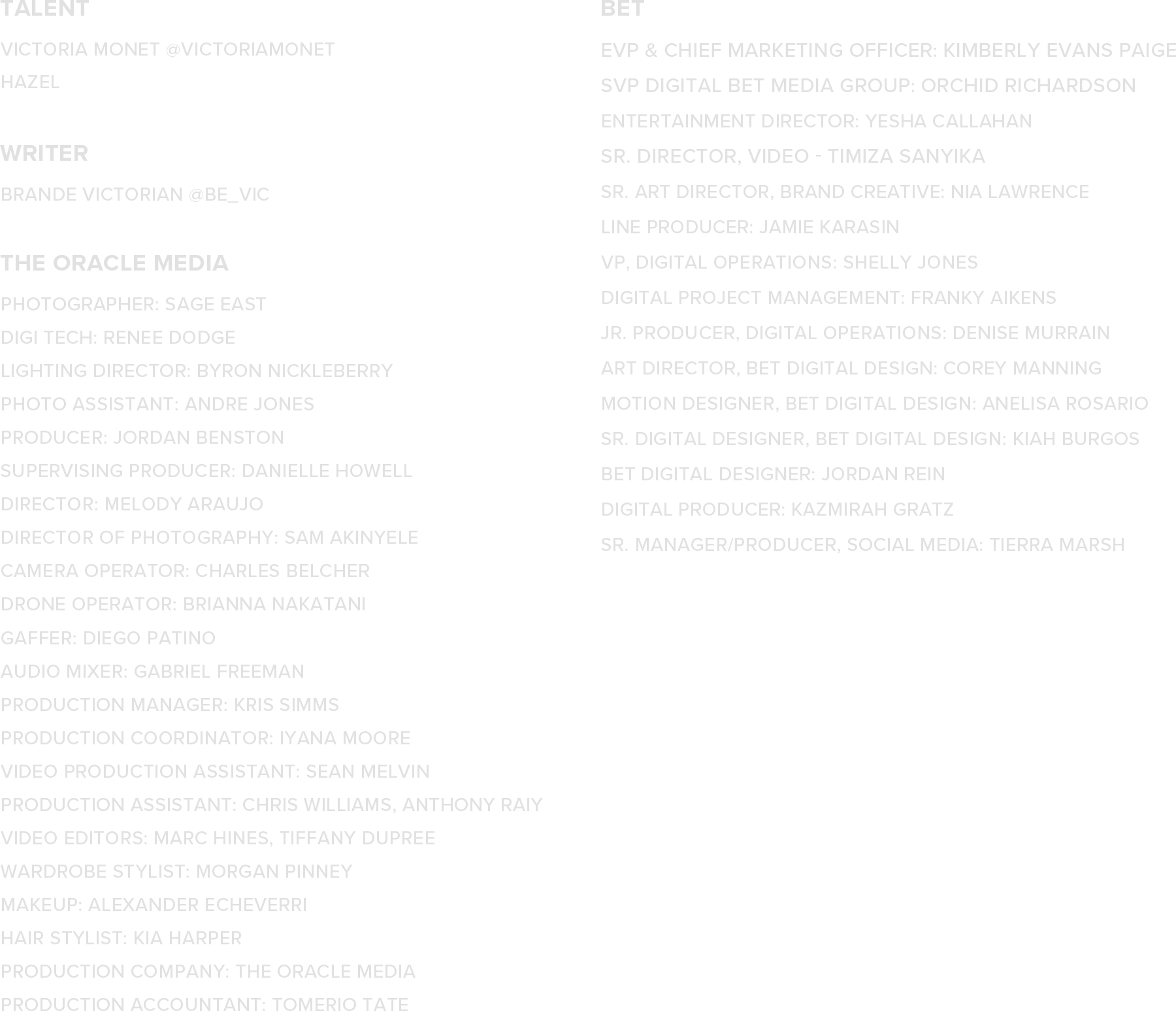

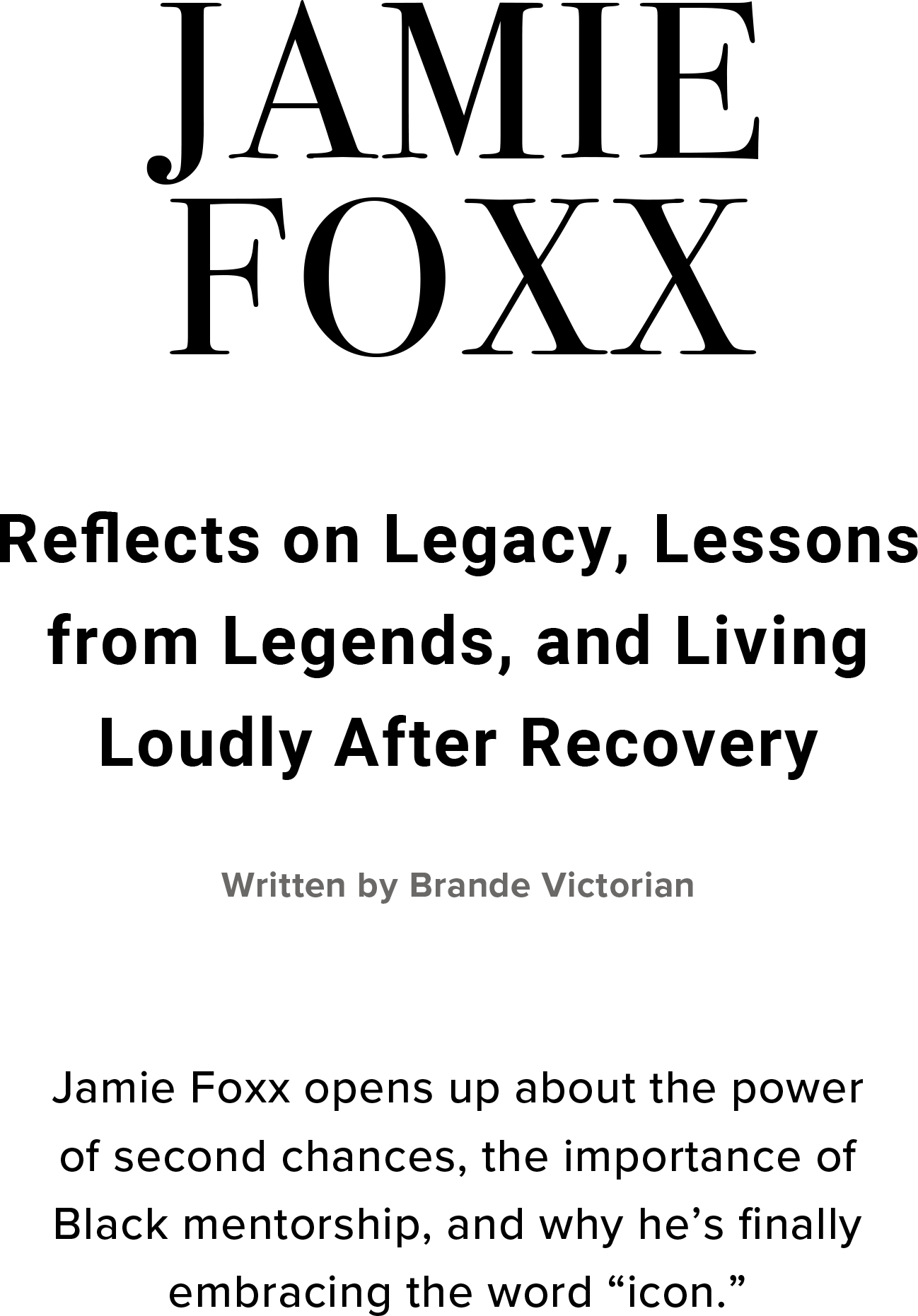

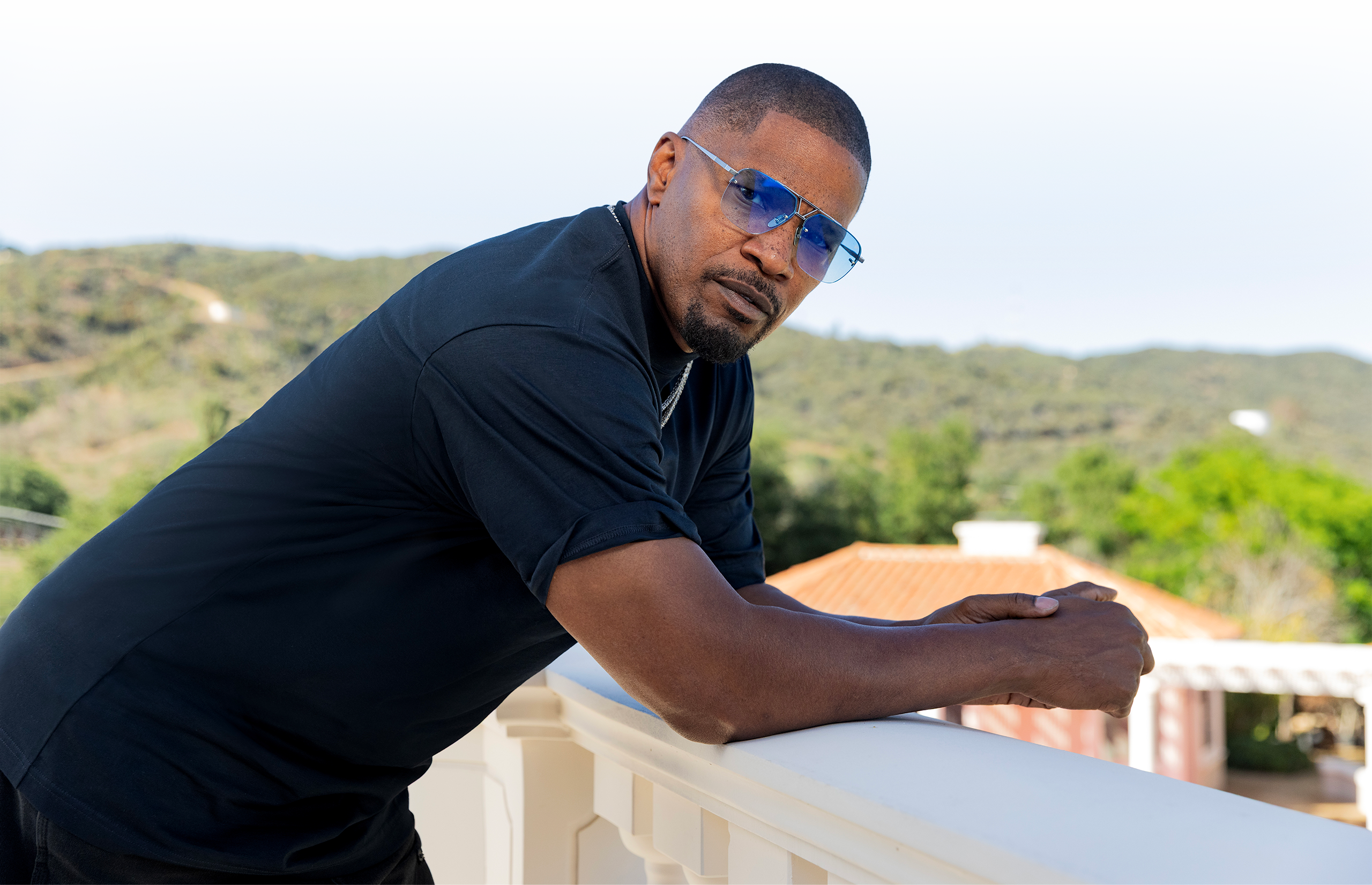

It’s been two years since Foxx suffered a brain bleed that led to a stroke in April 2023. The road to recovery was a long one for the entertainer and his family—particularly his sister and daughters, Corinne, 31, and Anelise, 16. Foxx made his first public appearance since his health crisis on December 3, 2023, when he accepted the Vanguard Award at the Critics Choice Association’s Celebration of Cinema and Television: Honoring Black, Latino, and AAPI Achievements.

One year later, on December 10, 2024, he premiered his Netflix stand-up special, Jamie Foxx: What Had Happened Was..., detailing the harrowing experience—just three months after walking his eldest daughter down the aisle at his home.

he first time I interviewed Jamie Foxx was backstage at the Urban One Honors ceremony in Washington, D.C., in December 2019. He was receiving an Icon��

he first time I interviewed Jamie Foxx was backstage at the Urban One Honors ceremony in Washington, D.C., in December 2019. He was receiving an Icon��

Award, though as he told me that day, he didn’t yet see himself as one. In June, the 57-year-old actor, comedian, and vocalist received an Icon Award at the BET Awards 2025 - now he sings a different tune.��

Never far behind is daughter Hazel, 4, who appeared on Monét’s seven-time Grammy nominated album Jaguar II which launched her into the mainstream zeitgeist after more than a decade of penning songs for artists like Ariana Grande, Nas, and Chloe x Halle, and building a personal fanbase with early projects such as Nightmares & Lullabies and Life After Love. Just in the past two years, Monét has won three Grammys, two Soul Train Music Awards, and two BET Awards, but there’s another, more subtle indicator Monét sees as a sign that her time has arrived.�

Never far behind is daughter Hazel, 4, who appeared on Monét’s seven-time Grammy nominated album Jaguar II which launched her into the mainstream zeitgeist after more than a decade of penning songs for artists like Ariana Grande, Nas, and Chloe x Halle, and building a personal fanbase with early projects such as Nightmares & Lullabies and Life After Love. Just in the past two years, Monét has won three Grammys, two Soul Train Music Awards, and two BET Awards, but there’s another, more subtle indicator Monét sees as a sign that her time has arrived.�

Monét’s ever-growing reach is undeniable; her Jaguar II tour sells out across North America in a matter of minutes and brings out stars such as Kelly Rowland, Issa Rae, Zendaya, and Justin Bieber to shows—names Hazel likely wouldn’t bat an eye at around the Monét household.�

Yet it kind of is for a toddler who’s already walked (or been carried across) major red carpets and made history as the youngest ever Grammy nominee for her feature on Jaguar II’s “Hollywood,” the song title perhaps a foreshadowing of her future following in her mother’s famous footsteps. There’s a bit of strategy behind Monét’s decision to bring her daughter into the public eye, though she admits overall, “I'm kind of winging it.”

“It’s always great to get it from your people, especially in today’s time where we’re being challenged on—not our merit—but our very existence, where we’re kind of scratching our head, and you go, ‘Well, I thought it was about the price of eggs.’ I guess t’s not,” he says. “It’s time for us to look within ourselves and acknowledge ourselves and prop ourselves up because it’s getting kind of weird out there.”

One of the residents of Foxx’s ranch property is Cheetah, the horse he rode in Django Unchained. His take on the titular character in Quentin Tarantino’s 2012 revisionist western sits alongside Willie Beamen in Any Given Sunday, Max in Collateral, Ray Charles in Ray, and Walter McMillian in Just Mercy, as one of Foxx’s greatest performances. It’s been 20 years since the Terrell, TX, native was up for an Academy Award for Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor, for Collateral, in the same night—ultimately winning the Oscar for Best Actor for the 2004 biopic of the blind soul music legend.

Two things stand out to Foxx about that time in his life. “We were partying too much,” he says, admitting the first. The second is Oprah Winfrey getting him together by taking him to see Sidney Poitier at the home of one of his mentors, Quincy Jones. “She reached out and said, ‘Hey, this is important. Because the Ray Charles performances a great performance’—decent,” he interjects, humbly correcting himself. “‘But it was a performance of redemption. It was a performance of a blind Black man becoming a world icon.’”

“To be able to win did a lot for us. I think it opened doors for ‘Whoop That Trick,’” he says, referencing Hustle & Flow, which won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for “It's Hard out Here for a Pimp” in 2006, “and Dreamgirls and things like that, so now they mention those movies in the Oscar category.”

Foxx, a producer of Apple TV+’s recent docuseries Number One on the Call Sheet, which celebrates the achievements of leading Black men and women in Hollywood, doesn’t play about the legends in his life—counting Winfrey among them. “The winds blow, and we get to thinking that our mentors aren’t what they are. They are. Knock it off. All you motherfuckers on social media talking that goofy shit, you have no idea what these people put down. We’ve got to hold the line.”

It’s the hypercritical nature of social media that’s made fame less fun than it used to be for Foxx. “I tell people all the time: Be careful what you wish for. Because I’m a gregarious dude and I just want to have fun. And sometimes people will take advantage of that—especially in today’s world. Now? You’ve got to be careful. Everything is looked at. Everything is scrutinized.”

Quincy Jones is one of the first mentors Foxx connected with when he moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in comedy. Just two years after telling jokes at an open mic night, Foxx joined the cast of Keenen Ivory Wayans’ hit sketch comedy show In Living Color in 1991. “Quincy Jones shared the camaraderie,” says Foxx. “I’ll get in trouble for saying that I don’t like battle rap, but I think sometimes it separates—just naturally. We love it, but Quincy would be like, ‘Sh-t, man. Me, Ray Charles, everybody —we were together, man,’” he says, imitating the producer and composer who passed away on November 3 at the age of 91. “Quincy would talk about moments of running into other talented people and being able to elevate because you ran into other talented people—which explains why, here at my house, I always have a get-together so other artists can come and run into other artists.”

Harry Belafonte was another key figure in Foxx’s journey. “Harry Belafonte taught me how to be a Black man,” he says. “I’m not a perfect Black man, but he taught me the significance of a Black entertainer versus anyone else. We carry a little bit more of a load. We not only are challenged with performing—we’re also challenged with holding the line when it comes to Black issues.”

Foxx isn’t self-righteous when it comes to the responsibility he says Belafonte—and also Poitier—passed on to him the night Winfrey introduced them at Jones’s home. “Everyone doesn’t have to do it. That doesn’t mean that every Black entertainer has to be the Blackest person in the world and do the Blackest things in the world. But if you’re able to, it means a lot. When you stand next to Sabrina and Trayvon [Martin]’s family, it means a lot. When you stand next to George Floyd’s family, it means a lot.”

t’s been two years since Foxx suffered a brain bleed that led to a stroke in April 2023. The road to recovery was a long one for the entertainer and his �

family—particularly his sister and daughters, Corinne, 31, and Anelise, 16. Foxx made his first public appearance since his health crisis on December 3, 2023, when he accepted the Vanguard Award at the Critics Choice Association’s Celebration of Cinema and Television: Honoring Black, Latino, and AAPI Achievements. One year later, on December 10, 2024, he premiered his Netflix stand-up special, amie Foxx: What Had Happened Was..., detailing the harrowing experience—just three months after walking his eldest daughter down the aisle at his home.

“I feel 85 sometimes. Sometimes I’m 75. Sometimes I’m 65. But I’m blessed, man,” Foxx says of his health six months after the special’s release. “We talk about algorithms and things like that when you’re doing a special, and I would always say in my head: I’m not an algorithm. I’m a miracle.”

A detail Foxx didn’t include in the special was that he didn’t remember any of the 67 nurses at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, GA, who helped keep him alive. When he went back to the medical center to meet them, one nurse told him that he was what she called a “three-percenter” —because fewer than three percent of people who come to the hospital in his condition survive.

“The reason I may go on with my jokes a little longer is because I didn’t think I was going to be able to tell a joke,” Foxx says, adding context to the quips he’s treated us to during the interview. “The reason I may sing or try to get my sister to laugh is because my sister was watching me fight—and that wasn’t in the handbook.”

“When you dream, you dream the best of everything. You dream this,” he says, holding out his hand as he looks around the room. You don’t dream that your sister is met with a decision that, if she doesn’t make it at that time, you’re no longer here. So I don’t take anything for granted. I don’t let anything get me down.”

now he sings a different tune.�

"I'm definitely iconic,” says Foxx. “Six years makes a difference, and I feel iconic.”�

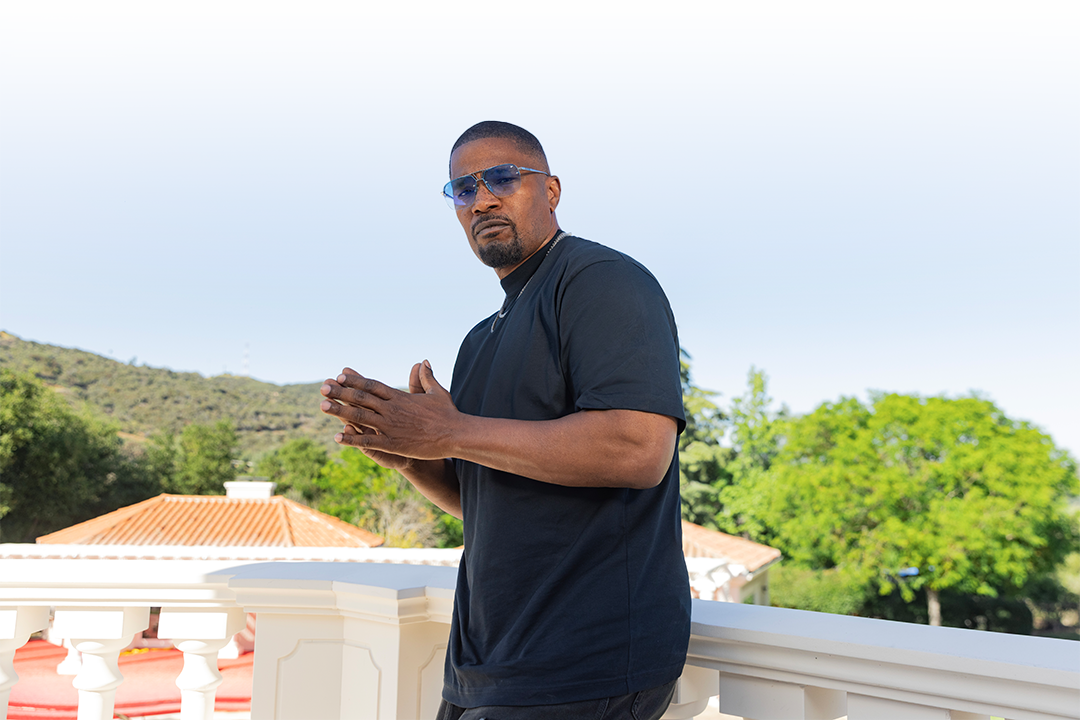

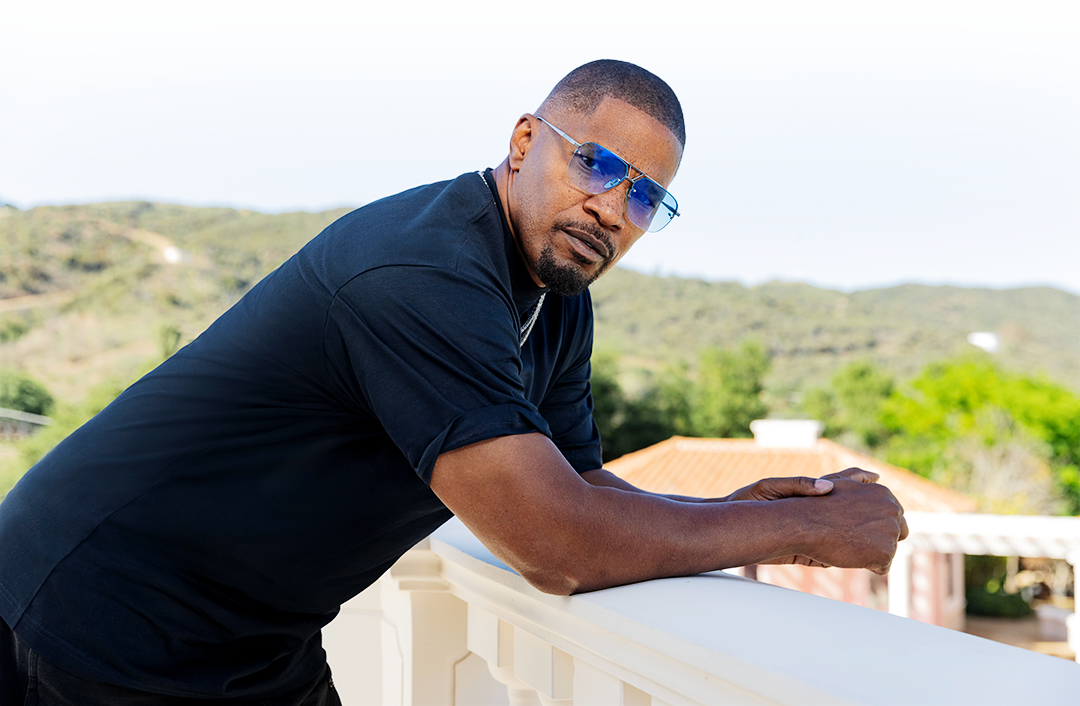

Foxx and I are talking in the living room of his 17,000-square-foot mansion in the Hidden Valley neighborhood of Thousand Oaks, CA. In front of us, digital images of Tupac and Biggie rotate on the wall. Behind us, lush green land—40 acres to be exact—provides a serene backdrop.�

“It’s commemorative of 40 acres and a mule, which I was blessed enough to have,” Foxx says of his property, referencing the failed land deal that freed slaves were promised after the Civil War. “Now, if we could just get everybody to get at least half an acre or something—or whatever they can give us—we’d love to get it rolling.”�

which I was blessed enough to have,” Foxx says of his property, referencing the failed land deal that freed slaves were promised after the Civil War. “Now, if we could just get everybody to get at least half an acre or something—or whatever they can give us—we’d love to get it rolling.”�

Foxx looks off to the side at his sister, Deidra Dixon, whom he suspects is giving him a look that says, “Don’t start.” Everyone in the room knows reparations are about as likely as the Trump administration admitting the DEI hire campaign they’ve been pushing since inauguration is anti-Black propaganda. But it’s the current sociopolitical climate that leaves Foxx feeling especially proud to be celebrated in this moment.�

�One of the residents of Foxx’s ranch property is Cheetah, the horse he rode in Django Unchained. His take on the titular character in Quentin Tarantino’s 2012 revisionist western sits alongside Willie Beamen in Any Given Sunday, Max in Collateral, Ray Charles in Ray, and Walter McMillian in Just Mercy, as one of Foxx’s greatest performances. It’s been 20 years since the Terrell, TX, native was up for an Academy Award for Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor, for Collateral, in the same night—ultimately winning the Oscar for Best Actor for the 2004 biopic of the blind soul music legend.�

“It’s always great to get it from your people, especially in today’s time where we’re being challenged on—not our merit—but our very existence, where we’re kind of scratching our head, and you go, ‘Well, I thought it was about the price of eggs.’ I guess it’s not,” he says. “It’s time for us to look within ourselves and acknowledge ourselves and prop ourselves up because it’s getting kind of weird out there.”�

�Two things stand out to Foxx about that time in his life. “We were partying too much,” he says, admitting the first. The second is Oprah Winfrey getting him together by taking him to see Sidney Poitier at the home of one of his mentors, Quincy Jones. “She reached out and said, ‘Hey, this is important. Because the Ray Charles performance is a great performance’—decent,” he interjects, humbly correcting himself. “‘But it was a performance of redemption. It was a performance of a blind Black man becoming a world icon.’”��

“I feel 85 sometimes. Sometimes I’m 75. Sometimes I’m 65. But I’m blessed, man,” Foxx says of his health six months after the special’s release. “We talk about algorithms and things like that when you’re doing a special, and I would always say in my head: I’m not an algorithm. I’m a miracle.”

A detail Foxx didn’t include in the special was that he didn’t remember any of the 67 nurses at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, GA, who helped keep him alive. When he went back to the medical center to meet them, one nurse told him that he was what she called a “three-percenter”—because fewer than three percent of people who come to the hospital in his condition survive.

“The reason I may go on with my jokes a little longer is because I didn’t think I was going to be able to tell a joke,” Foxx says, adding context to the quips he’s treated us to during the interview.

“The reason I may go on with my jokes a little longer is because I didn’t think I was going to be able to tell a joke,” Foxx says, adding context to the quips he’s treated us to during the interview.

“The reason I may sing or try to get my sister to laugh is because my sister was watching me fight—and that wasn’t in the handbook.”

“When you dream, you dream the best of everything. You dream this,” he says, holding out his hand as he looks around the room. “You don’t dream that your sister is met with a decision that, if she doesn’t make it at that time, you’re no longer here. So I don’t take anything for granted. I don’t let anything get me down.”

Requesting a response from his sister and team in the corner of the room, Foxx says, “My saying is what? No bad days.” So it’s no bad days,” Foxx continues. “If you see me jump for joy, get to shouting, or doing whatever—it’s because, as they would say, ‘You got a second chance.’ At first, I was like, ‘I don’t want no second chance—I want my first chance.’ But you get that second chance, and when I tell you? You better live that thing, man. You’ve got to live it.”

he first time I interviewed Jamie Foxx was backstage at the Urban One Honors ceremony in Washington, D.C., in December 2019. He was receiving an Icon Award, though as he told me that day, he didn’t yet see himself as one. In June, the 57-year-old actor, comedian, and vocalist received an Icon Award at the BET Awards 2025 - now he sings a different tune.

JAMIE FOXX

@IAMJAMIEFOXX

Back to Top

�

�“To be able to win did a lot for us. I think it opened doors for Whoop That Trick,’” he says, referencing Hustle & Flow, which won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for “It's Hard out Here for a Pimp” in 2006, “and Dreamgirls and things like that, so now they mention those movies in the Oscar category.”�

�Foxx, a producer of Apple TV+’s recent docuseries Number One on the Call Sheet, which celebrates the achievements of leading Black men and women in Hollywood, doesn’t play about the legends in his life—counting Winfrey among them. “The winds blow, and we get to thinking that our mentors aren’t what they are. They are. Knock it off. All you motherfuckers on social media talking that goofy shit, you have no idea what these people put down. We’ve got to hold the line.”�

�Quincy Jones is one of the first mentors Foxx connected with when he moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in comedy. Just two years after telling jokes at an open mic night, Foxx joined the cast of Keenen Ivory Wayans’ hit sketch comedy show In Living Color in 1991. “Quincy Jones shared the camaraderie,” says Foxx. “I’ll get in trouble for saying that I don’t like battle rap, but I think sometimes it separates—just naturally. We love it, but Quincy would be like, ‘Sh-t, man. Me, Ray Charles, everybody—we were together, man,’” he says, imitating the producer and composer who passed away on November 3 at the age of 91. “Quincy would talk about moments of running into other talented people and being able to elevate because you ran into other talented people—which explains why, here at my house, always have a get-together so other artists can come and run into other artists.”�

�Harry Belafonte was another key figure in Foxx’s journey. “Harry Belafonte taught me how to be a Black man,” he says. “I’m not a perfect Black man, but he taught me the significance of a Black entertainer versus anyone else. We carry a little bit more of a load. We not only are challenged with performing—we’re also challenged with holding the line when it comes to Black issues.”�

�It’s the hypercritical nature of social media that’s made fame less fun than it used to be for Foxx. “I tell people all the time: Be careful what you wish for. Because I’m a gregarious dude and I just want to have fun. And sometimes people will take advantage of that—especially in today’s world. Now? You’ve got to be careful. Everything is looked at. Everything is scrutinized.”��

�Foxx isn’t self-righteous when it comes to the responsibility he says Belafonte—and also Poitier—passed on to him the night Winfrey introduced them at Jones’s home. “Everyone doesn’t have to do it. That doesn’t mean that every Black entertainer has to be the Blackest person in the world and do the Blackest things in the world. But if you’re able to, it means a lot. When you stand next to Sabrina and Trayvon [Martin]’s family, it means a lot.�

table of contents

close

table of contents

Close