Far away from

human rights

n October 2022, a British-American couple, Kyle and Maryanne Webb, were sailing their yacht through a remote area of the Indian Ocean just south of the Saya de Malha Bank. The Webbs are sailing enthusiasts, and they had covered tens of thousands of miles on their vessel, the Begonia, over the previous years. As they passed the bank, they spotted a small fishing vessel, about 55 feet in length, painted bright yellow and turquoise, with about a dozen red and orange flags billowing from the roof of its cabin. It was a Sri Lankan gill net boat, the Hasaranga Putha.

Looking gaunt and desperate, the crew, having sailed roughly 2,000 miles from their home port in Beruwala, Sri Lanka, told the Webbs they had been at sea for two weeks and had only caught four fish. They begged the Webbs for food, soda, and cigarettes. The Webbs gave them what they could, including fresh water, and then headed on their way. “They were clearly in a struggling financial position,” Maryanne Webb says. “It broke my heart to see the efforts they feel they must go to to provide for their families.”

A month later, again near the Saya de Malha Bank, the Hasaranga Putha hailed another vessel, the South African ocean research and supply ship S.A. Agulhas II, which was on an expedition in the Saya de Malha for Monaco Explorations. By this time, the Sri Lankan crew was almost out of fuel, so they begged for diesel from the new passerby. The scientists did not have the right type of fuel to offer, but they still boarded a dinghy and brought the fishers water and cigarettes. The Sri Lankans gave the scientists fish in appreciation. The Sri Lankan fishers would remain at sea for another six months, not returning to Colombo until April 2023.�

Directed by Ben Blankenship; Executive Producer: Ian Urbina�

By Ian Urbina, Maya Martin, Susan Ryan, Joe Galvin, and Austin Brush

Part 1

Robbing a bank when no one's looking

Jesica Reyes

Hundreds of miles from the nearest port, the Saya de Malha Bank is one of the most remote areas on the planet, which means it can be a harrowing workplace for the thousands of fishers from a half-dozen countries who make this perilous journey. The farther from shore vessels travel and the more time they spend at sea, the more the risks pile up: Dangerous storms, deadly accidents, malnutrition, and physical violence are common threats faced by distant-water crews. The longest trips made annually, often in the least-equipped boats, are undertaken by a fleet of several dozen Sri Lankan gillnetters.

Some of the vessels that fish the Saya de Malha Bank engage in a practice called transshipment, where they offload their catch to refrigerated carriers without returning to shore, so that they can remain fishing on the high seas for longer periods of time. Fishing is the most dangerous occupation in the world, and more than 100,000 fishers die on the job each year. When they do, particularly on longer journeys far from shore, it is not uncommon for their bodies to be buried at sea.

But Sri Lankan gillnetters are not the only vessels making a perilous journey to fish this biodiverse seascape. Thai fishmeal trawlers also target these waters, traveling more than 2,500 nautical miles from the port of Kantang, Thailand. At its height, this fleet numbered above 70 vessels, which were decimating the sea grass and were notorious for their working conditions.

In January 2016, for example, three of these ships left the Saya de Malha Bank and returned to Thailand. During the journey, 38 Cambodian crew members fell ill, and by the time they returned to port, six had died. The remaining sick crew were hospitalized and treated for beriberi, a disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin B1, or thiamine. Symptoms include tingling, burning, numbness, difficulty breathing, lethargy, chest pain, dizziness, confusion, and severe swelling.�

Monaco Explorations

Easily preventable yet fatal if left untreated, beriberi has historically appeared in prisons, asylums, and migrant camps, but it has largely been stamped out. Experts say that when it occurs at sea, beriberi often indicates criminal neglect (one medical examiner described it as “slow-motion murder”), because it is so easily treatable and avoidable.

The disease has become more prevalent on distant-water fishing vessels in part because ships stay so long at sea, a trend facilitated by transshipment. Working practices involving hard labor and long working hours cause the body to deplete vitamin B1 at a faster metabolic rate to produce energy, the Thai government concluded in a report on the deaths. Further research done by Greenpeace found that some of the workers were victims of forced labor.

Today, fewer vessels from the Thai fleet are traveling to the Saya de Malha Bank, but some still make the trip, and questions about their working conditions linger.

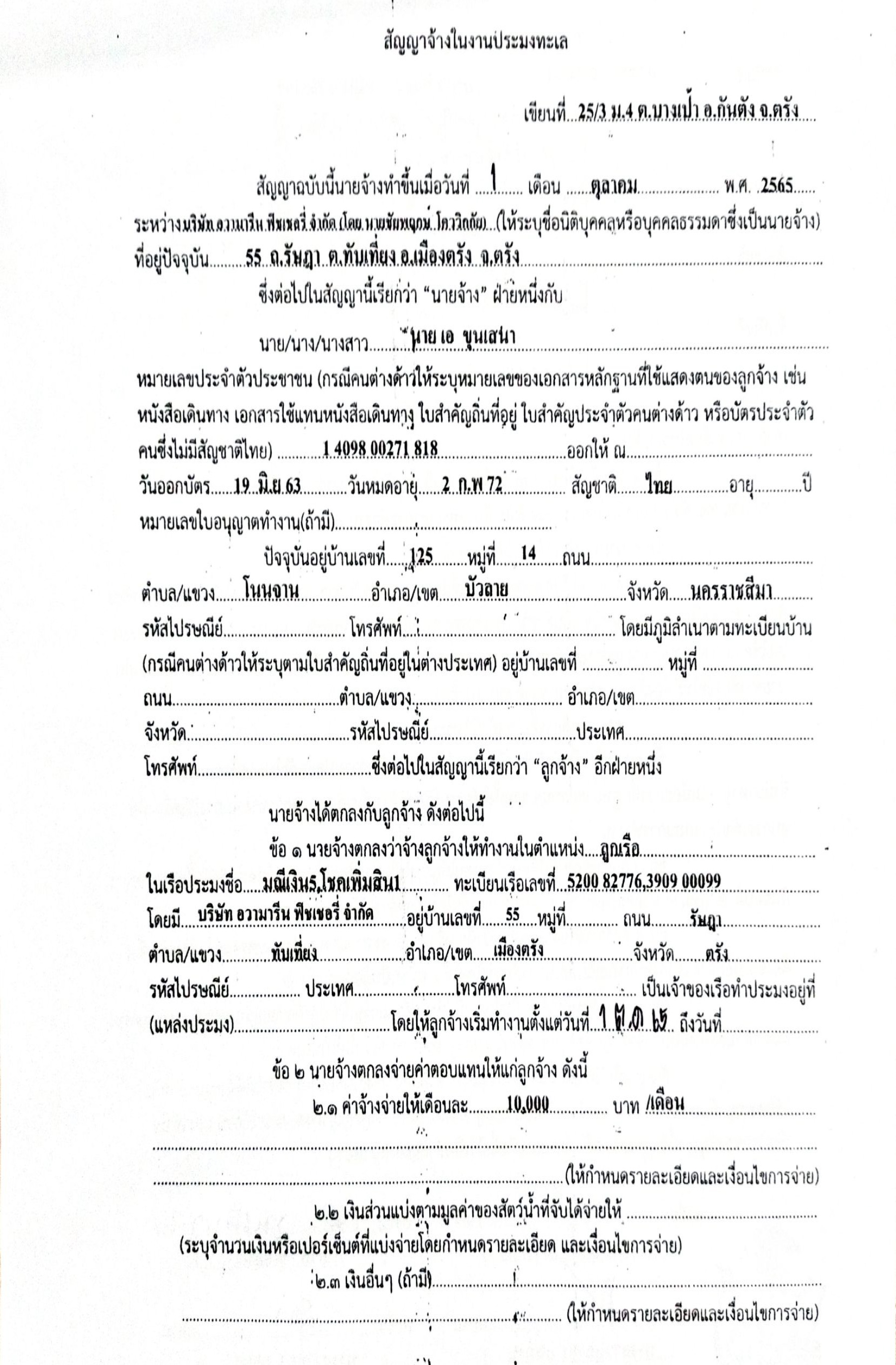

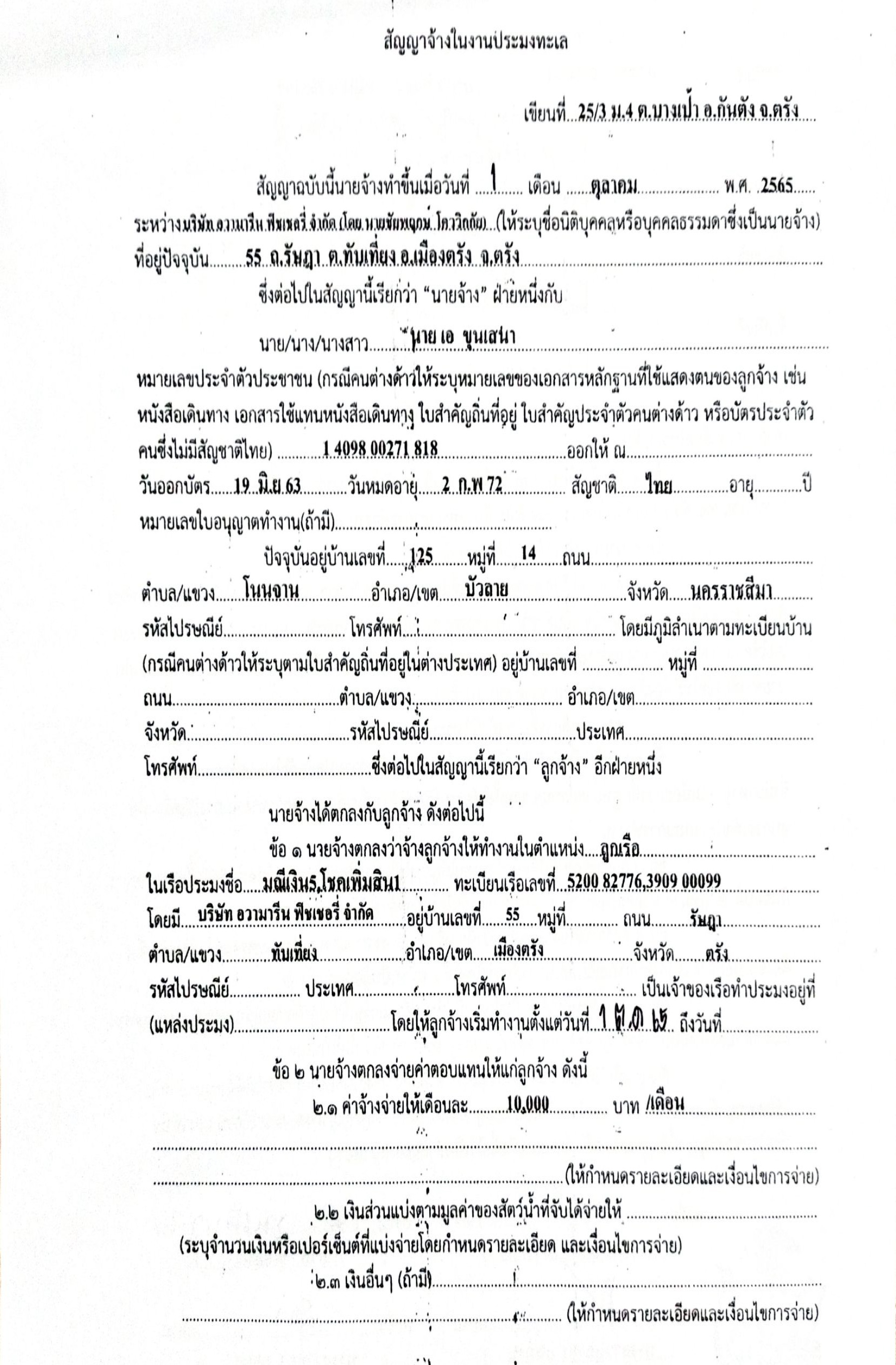

In April 2023, one of those vessels, the Chokephoemsin 1, a bright blue 90-foot trawler, set out for the Saya de Malha Bank. A crew member named Ae Khunsena boarded the ship in Samut Prakan, Thailand, for a five-month tour, according to a report compiled by Stella Maris, a nonprofit organization that helps fishers. As is typical on high-seas vessels, the hours were long and punishing. Khunsena earned 10,000 baht, or about $288, per month, according to his contract.

Robbing a bank �when no one's looking

Part 1

In 2022, it took nearly six months for a small Sri Lankan fishing vessel, the Hasaranga Putha, to travel the nearly 2,000 miles to the Saya de Malha bank. By the time it arrived, it was desperately short on fuel, water, and supplies.

Swollen feet are a telltale sign of beriberi caused by nutrition deficiency.

I

Ian Urbina, Maya Martin, Susan Ryan, Joe Galvin, and Austin Brush are editors at The Outlaw Ocean Project, a non-profit journalism organization focused on investigative stories about issues on the high seas.

GLOBE OPINION Editors: Jim Dao, Brian Bergstein, and Kelly Horan; Design: Heather Hopp-Bruce;

Audience engagement editor: Karissa Korman; Developer: Andrew Nguyen; Copy editor: Karen Schlosberg

Ae Khunsena’s family provided Stella Maris with his employment contract, which revealed that he was due to receive a wage of 10,000 baht, or $288, per month.

Stella Maris / The Outlaw Ocean Project

In one of his last calls to his family through Facebook, Khunsena said he had witnessed a fight that resulted in more than one death. He said the body of a crew member who was killed was brought back to the ship and kept in the freezer. When Khunsena’s family pressed for details, he said he would tell them more later. He added that another Thai crew member who also witnessed the killing had been threatened with death and had fled the ship while it was still near the Thai coast. (A company official contested this claim and said no such fight happened, adding that there was an observer from the Department of Fisheries aboard the vessel, who would have reported such an incident had it happened.) Khunsena’s family spoke to him for the last time on July 22, 2023.

On July 29, while working in waters near Sri Lanka, Khunsena went overboard, off the stern of the ship. The incident was captured on a ship security camera. A man named Chaiyapruk Kowikai, listed as Khunsena’s employer on his contract, told Khunsena’s family that he had jumped. The ship’s captain had spent a day unsuccessfully searching the area to rescue him before returning to fishing, Kowikai said.

The vessel returned to port in Thailand roughly two months later. Police and company and insurance officials eventually concluded that Khunsena’s death was likely a suicide. This claim seemed to be backed up by the onboard footage, which does not show anyone near him when he went over the side of the boat. �

In the 13 seconds of footage recorded on July 29, 2023, a shirtless man appears to climb over the railing of the JDP and jump into the water behind the ship.

Stella Maris / The Outlaw Ocean Project

In September 2024, a reporting team from The Outlaw Ocean Project visited Khunsena’s village. Settled by rice farmers about a century ago, Non Siao is located in Bua Lai District, Nakhon Ratchasima, roughly 200 miles northeast of Bangkok. The reporting team interviewed Khusena’s mother and cousin as well as the local labor inspector, police chief, aid worker, and an official from the company that owned the ship. While the police and company officials said the death was likely a suicide, Khusena’s family strongly disagreed. “Why would he jump?” said Palita, Khunsena’s cousin. She explained why she highly doubted that Khusena took his own life: “He didn't have any problems with anyone.” Sitting on the ground under an overcast sky as she spoke with the reporter in a follow-up conversation by video chat, Palita went silent and looked down at her phone. “He wanted to see me,” added Khusena’s mother, Boonpeng Khunsena, who also doubted his suicide, since he kept saying in calls that he intended to be home by Mother’s Day.

As is often the case with crimes at sea, where evidence is limited and witnesses are few and frequently unreliable, it is difficult to know whether Khusena died by foul play. Perhaps, as his family speculated in interviews with The Outlaw Ocean Project, he witnessed a violent crime and was then silenced by being ordered to jump overboard. Perhaps, instead, he jumped willingly from the ship, a suicidal gesture likely driven by depression or mental health issues. In either scenario, the point remains the same: These distant-water ships travel so far from shore that the working and living conditions are brutal and sometimes violent. And these very conditions are likely playing a role in sinister outcomes.

And yet the human tragedy that crisscrosses this remote patch of high seas is not just tied to fishers. The Saya de Malha Bank has also become a transit route for migrants fleeing Sri Lanka. Since 2016, hundreds of Sri Lankans have attempted to make the perilous journey on fishing boats to the French-administered island of Réunion, in the Indian Ocean, some making the journey directly from the Saya de Malha. Those who do succeed in making landfall on Réunion are often repatriated. In one case, on Dec. 7, 2023, the Imul-A-0813 KLT, a Sri Lankan vessel that had spent the previous three months fishing in the Saya de Malha, illegally entered the waters around Réunion. Its seven crew members were apprehended by local authorities and repatriated to Sri Lanka two weeks later. Joining them on the repatriation flight were crew members of two other Sri Lankan fishing vessels that had previously been detained by Réunion authorities.

With near-shore stocks overfished in Thailand and Sri Lanka, vessel owners send their crews farther and farther from shore in search of a profitable catch. That is what makes the Saya de Malha — far from land, poorly monitored, and with a bountiful ecosystem — such an attractive target. But the fishers forced to work there live a precarious existence, and for some, the long journey to the Saya de Malha is the last they will ever take.�

Series

Vanishing protectors and predators

Part 2

Kyle Webb / The Outlaw Ocean Project

In October 2022, the Hasaranga Putha encountered a catamaran called the Begonia on the southern edge of Saya de Malha and the crew asked the Americans on board for help.

In November 2022, the Hasaranga Putha approached a Monaco Explorations research vessel, its crew begging for fuel, water, and cigarettes. The scientists aboard the research vessel provided assistance to the Sri Lankans by delivering water and cigarettes, but they did not have the type of fuel the smaller vessel required.

Monaco Explorations

On Oct. 8, 2021, six months after he boarded the Chokephoemsin 1, Ae Khunsena posted a few photos of himself on the ship on Tiktok.

Ae Khunsena

WARNING: This video contains graphic imagery

Ae Khunsena

Vanishing protectors and predators

Part 2

Part 3

WARNING:

This video contains graphic imagery

Vanishing protectors and predators

Part 2

Vanishing protectors and predators

Part 2

WARNING: This video contains graphic imagery

Video will be here at publication��For now, watch video here

MORE FROM THE OUTLAW OCEAN PROJECT��The return of an old scourge reveals a deep sickness in the global fishing industry

Chinese fishing vessels stay at sea for years at a time, forcing their crews to confront severe malnutrition. Americans who eat seafood are implicated too.

�Taking over from the inside: How China became the superpower of seafood

By buying access to other countries’ territorial waters, China has extended questionable fishing and labor practices around the world.

MORE FROM THE OUTLAW OCEAN PROJECT��The return of an old scourge reveals a deep sickness in the global fishing industry

Chinese fishing vessels stay at sea for years at a time, forcing their crews to confront severe malnutrition. Americans who eat seafood are implicated too.

�Taking over from the inside: How China became the superpower of seafood

By buying access to other countries’ territorial waters, China has extended questionable fishing and labor practices around the world.