BUILDING COMMUNITIES OF HOPE | 2020 SPECIAL REPORT

Creating a better future for children and families in a time of crisis

EXPLORE

This special report reflects the dramatically transformed landscape for children and families as the country confronts a global pandemic, economic disruption and its history of systemic racism. Here you will find stories of adaptation and innovation across the United States that are helping lead the way to the development of a true child and family well-being system centered on the vision of Building Communities of Hope. We invite you to explore this report, utilize the shared resources and join us in creating a better future for children and families.

Now is the time when we must move boldly past the differences that we have allowed to separate us and see instead the many commonalities we all share that must become the force that unites us. This includes our shared desire to be safe and supported in our homes, our families and our communities. We must come together, motivated by our shared desire to create a better future for our children and our children’s children.

The passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018 was a bold and important recognition that communities can and must transform their approaches to serving children and families. It was a critical step forward in recognizing that families are our greatest asset in ensuring children are safe and cared for.

We have watched as communities across the country have begun to rise to that opportunity and begin to move from the child welfare system as we know it to a true child and family well-being system that provides the foundations all families need.

Today, change is no longer a choice.

COVID-19 has required many of our partners to adapt and transform overnight. It has laid bare the underlying inequitable investments and opportunities in the ZIP codes where many of the families who are struggling the most live every day. It has demanded strong leadership, courage and a vision for a better future.

Already we are seeing great leaps forward and unexpected rewards that come from thinking, planning and acting in new ways based on what we know works best for children and families.

In this report, we take a first look at how communities are innovating to reach families — creating positive changes to carry them through the crisis and beyond. These stories are evolving as community leaders assess the outcomes of their work. We will continue to update and add to the examples highlighted here as more information becomes available.

We hope this report inspires leaders from all five sectors of our society to support the kinds of transformation that these times require of all of us. We believe it will inspire hope for the future of all of our children and families for generations to come.

Sincerely,

William C. Bell, Ph.D.

President and CEO

The safety and well-being of children cannot be seen as separate from the safety and well-being of their families. And the safety and well-being of those families are intrinsically tied to the support and opportunities provided by the communities where they live. In the words of a birth mother with experience in the child welfare system, we must shift our thinking: “Please don’t save me from my parents. Save my parents for me.”

The outpouring of grief and anger in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd and many, many other people of color through the years has led to a focus on how we allocate resources for public safety in our communities. We must ask ourselves the same difficult questions when it comes to the allocation of resources to ensure the safety of our children and families.

Today, it is clearer than ever that we must reallocate our investments in children and families. Rather than spending the bulk of funding separating children from families, communities have an opportunity to reallocate resources in hope-inspiring services and family supports that will ensure children are safe and have the opportunities they need in life.

The passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018 was a bold and important recognition that communities can and must transform their approaches to serving children and families. It was a critical step forward in recognizing that families are our greatest asset in ensuring children are safe and cared for.

We have watched as communities across the country have begun to rise to that opportunity and begin to move from the child welfare system as we know it to a true child and family well-being system that provides the foundations all families need.

Today, change is no longer a choice.

COVID-19 has required many of our partners to adapt and transform overnight. It has laid bare the underlying inequitable investments and opportunities in the ZIP codes where many of the families who are struggling the most live every day. It has demanded strong leadership, courage and a vision for a better future.

Already we are seeing great leaps forward and unexpected rewards that come from thinking, planning and acting in new ways based on what we know works best for children and families.

In this report, we take a first look at how communities are innovating to reach families — creating positive changes to carry them through the crisis and beyond. These stories are evolving as community leaders assess the outcomes of their work. We will continue to update and add to the examples highlighted here as more information becomes available.

We hope this report inspires leaders from all five sectors of our society to support the kinds of transformation that these times require of all of us. We believe it will inspire hope for the future of all of our children and families for generations to come.

Sincerely,

William C. Bell, Ph.D.

President and CEO

More than ever, these times call for a true investment in hope.

At Casey Family Programs, we have long believed that the well-being of all children and families can best be achieved by building Communities of Hope. These are places where every child and family has access to the supports and opportunities they need to thrive. They are places where all five sectors of society — government, business, nonprofit and faith-based, philanthropy and the community members themselves — recognize a shared responsibility and a shared commitment to ensure the health and well-being of every child and family.

For far too many families, Communities of Hope have remained only a vision. Over many decades, we as a nation have created child welfare systems with the intention of keeping children safe from abuse and neglect. But these systems rely primarily on waiting for children to be harmed and then separating them from their families and communities to keep them safe. And it is the children and families in that “Other America” that are disproportionately affected by this system.

Data, research and our own experience show us time and time again that the children we “rescue” likely face a lifetime of challenges and poor outcomes in education, employment, and mental and physical health. Children of color, children in tribal nations, and children in poor and marginalized communities are hurt the most by this system.

The safety and well-being of children cannot be seen as separate from the safety and well-being of their families. And the safety and well-being of those families are intrinsically tied to the support and opportunities provided by the communities where they live. In the words of a birth mother with experience in the child welfare system, we must shift our thinking: “Please don’t save me from my parents. Save my parents for me.”

The outpouring of grief and anger in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd and many, many other people of color through the years has led to a focus on how we allocate resources for public safety in our communities. We must ask ourselves the same difficult questions when it comes to the allocation of resources to ensure the safety of our children and families.

Today, it is clearer than ever that we must reallocate our investments in children and families. Rather than spending the bulk of funding separating children from families, communities have an opportunity to reallocate resources in hope-inspiring services and family supports that will ensure children are safe and have the opportunities they need in life.

The passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018 was a bold and important recognition that communities can and must transform their approaches to serving children and families. It was a critical step forward in recognizing that families are our greatest asset in ensuring children are safe and cared for.

We have watched as communities across the country have begun to rise to that opportunity and begin to move from the child welfare system as we know it to a true child and family well-being system that provides the foundations all families need.

Today, change is no longer a choice.

COVID-19 has required many of our partners to adapt and transform overnight. It has laid bare the underlying inequitable investments and opportunities in the ZIP codes where many of the families who are struggling the most live every day. It has demanded strong leadership, courage and a vision for a better future.

Already we are seeing great leaps forward and unexpected rewards that come from thinking, planning and acting in new ways based on what we know works best for children and families.

In this report, we take a first look at how communities are innovating to reach families — creating positive changes to carry them through the crisis and beyond. These stories are evolving as community leaders assess the outcomes of their work. We will continue to update and add to the examples highlighted here as more information becomes available.

We hope this report inspires leaders from all five sectors of our society to support the kinds of transformation that these times require of all of us. We believe it will inspire hope for the future of all of our children and families for generations to come.

Sincerely,

William C. Bell, Ph.D.

President and CEO

Hope and the responsibility to change lives

COVID-19 has required many of our partners to adapt and transform overnight. It has laid bare the underlying inequitable investments and opportunities in the ZIP codes where many of the families who are struggling the most live every day. It has demanded strong leadership, courage and a vision for a better future.

Already we are seeing great leaps forward and unexpected rewards that come from thinking, planning and acting in new ways based on what we know works best for children and families.

In this report, we take a first look at how communities are innovating to reach families — creating positive changes to carry them through the crisis and beyond. These stories are evolving as community leaders assess the outcomes of their work. We will continue to update and add to the examples highlighted here as more information becomes available.

We hope this report inspires leaders from all five sectors of our society to support the kinds of transformation that these times require of all of us. We believe it will inspire hope for the future of all of our children and families for generations to come.

Sincerely,

William C. Bell, Ph.D.

President and CEO

Today, change is no longer a choice.

The outpouring of grief and anger in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd and many, many other people of color through the years has led to a focus on how we allocate resources for public safety in our communities. We must ask ourselves the same difficult questions when it comes to the allocation of resources to ensure the safety and well-being of our children and families.

Today, it is clearer than ever that we must reallocate our investments in children and families. Rather than spending the bulk of funding separating children from their families and communities, we have an opportunity to reallocate resources in hope-inspiring services and family supports that will ensure children are safe and have the opportunities they need in life.

The passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018 was a bold and important recognition that we as a nation can and must transform our approaches to meeting the well-being needs of children, families and communities. It was a critical step forward in recognizing that families and communities are our greatest assets in ensuring that children are safe and well cared for.

We have watched as communities across the country have begun to rise to that opportunity and begun the path forward to move from the child welfare system of our past to a true child and family well-being system that provides the foundations that all families need to ensure that their children grow up surrounded by Communities of Hope.

Today, change is no longer just about a choice that we should make, it is the mandate that will determine our future as a nation.

The safety and well-being of children cannot be seen as separate from the safety and well-being of their families.

It is the children and families in that “Other America” who are most disproportionately affected by this system — a system that in the name of offering help, inflicts further harm, sometimes with tragic life-altering results. The death of a 16-year-old young man, after being restrained at a residential youth facility in Michigan this year, requires us to confront the actions we need to take to move away from what has become a harmful, intrusive child welfare system to a more holistic prevention-oriented child well-being system.

Data, research and our own experience show us time and time again that the children whose lives we touch through our historical “child rescue/child protection” framework likely face a lifetime of challenges, including poor outcomes in education, employment, mental health and physical health. Children of color, children in tribal nations, children in income insufficient communities and marginalized communities are hurt the most by this system.

The safety and well-being of children cannot be seen as separate from the safety and well-being of their families. We must also embrace the equally important fact that the safety and well-being of those families are intrinsically tied to the support and opportunities provided by the communities where they live.

At Casey Family Programs, we have long believed that the well-being of all children and families can best be achieved by building Communities of Hope. These are places where every child and family has access to the supports and opportunities they need to thrive. Communities of Hope are places where all five sectors of society — government, business, nonprofit (including faith-based and civic organizations), philanthropy and the community members themselves — recognize a shared responsibility and a shared commitment to ensure the health, well-being and right to thrive of every child and family.

For far too many families, Communities of Hope have remained only a vision. Over many decades, we as a nation have created child welfare systems with the intention of keeping children safe from abuse and neglect. But these systems rely primarily on waiting for children to be harmed and then separating them from their families and communities to keep them safe.

More than ever, these times call for a true investment in hope.

The COVID-19 pandemic is threatening children, families and communities across the nation and around the world. The resulting economic devastation has created uncertainty for millions of people. The tragic deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others have touched off a long overdue reckoning of the role that institutional racism and discrimination have played throughout our history as a nation and in the systems we have built. Most recently this has been exacerbated by the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

It is sadly no surprise that Black, Latinx and Native American children and families, along with families who live in poor and marginalized ZIP codes, have been hardest hit during this dual pandemic. They live in what Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called “The Other America,” a place where children and families are denied the life-sustaining investments in the kinds of educational, economic, nutritional and health care supports and opportunities that so many other communities take for granted in this nation.

Now is the time when we must move boldly past the differences that we have allowed to separate us and see instead the many commonalities we all share that must become the force that unites us. This includes our shared desire to be safe and supported in our homes, our families and our communities. We must come together, motivated by our shared desire to create a better future for our children and our children’s children.

These are daunting times.

President and CEO

Dr. William C. Bell

Hope and the responsibility to change lives

Building Communities of Hope | Creating a better future for children and families in a time of crisis

“We have been able to keep a constant check on every single elder in our community,” Mayer says. “We also made sure every elder has a laser thermometer, a blood pressure cuff, a pulse oximeter, sweetgrass, sage, a medicine wheel and a copy of our latest newsletter.”

Caring first for elders — those who are 60 and older — is the natural order for the tribes. “Elders are the second line of defense for the safety of our children,” Fox says. “Whatever services our elders need, the tribe is going to provide them those services.”

As a result of high incidences of substance use in MHA Nation among adults, many children have been separated from their parents and are living with their grandparents. Mayer says she hopes the tribes can apply the lessons of their effective community response to COVID-19 to the epidemic of drug use. “We have two states of emergency we are dealing with here,” Mayer says. “But the one affecting our family structure most right now isn’t COVID, it’s the drug activity.” That activity not only is dividing children and parents, it is isolating those parents from their strongest system of support — their tribe, which is their family.

Learn More

Zero COVID-19 Fatalities

AS OF JULY 1, 2020

MHA NATION

As of July 1, no resident of the Fort Berthold Reservation has died of coronavirus. Of the 1,398 people tested for COVID-19, 42 have tested positive. For about five weeks in the spring, there were no new cases, with Mayer attributing recent diagnoses to people becoming complacent and traveling off the reservation.

“When it comes to keeping children safe, it’s all about family structure — however that looks,” says Monte Fox, a senior director for Casey Family Programs who was raised on MHA Nation land. “In Native American families, when parents are struggling, grandparents most often will step in to care for the kids. A family dynamic that may not seem familiar to the outside world feels entirely normal inside the reservation.”

On Native lands, family is defined broadly, stretching across multiple generations where elders hold the highest honor and culture provides the glue to who we are as Native people. Family also extends into the entire community, powered by a spirit of clanship where every member of a tribe is accountable to keep everyone else healthy and well protected.

To protect people from COVID-19, MHA Nation revived a cultural tradition that dates back at least to the days of the smallpox epidemic — a camp crier. A tribe member, who inherited the honor of being camp crier from his father, drove around the reservation in the back of a pickup truck, carrying a microphone attached to a loudspeaker. His amplified instructions reminded everyone to stay home, maintain social distance, wear a mask, wash their hands and keep their home clean.

“We are all products of our experience and our ancestors,” says Dr. Monica Mayer, a physician and member of MHA Nation’s Tribal Business Council. “Health, safety and survivability have been at the forefront of our people for hundreds of years.”

The tribal council also restricted travel to within the reservation, established a dusk-to-dawn curfew, and limited gatherings to no more than five people. “In a lot of communities, I think it’s been hard to get people to listen to and follow what the authorities are saying about COVID,” Mayer says. “In our communities, when the elders said, ‘Stay home,’ people listened.”

– MONTE FOX, Senior Director, Casey Family Programs

When it comes to keeping children safe, it’s all about family structure — however that looks.

The self-governing nation mobilized quickly to keep the 5,000 members living on the reservation safe, borrowing hard lessons learned from the tribes’ resilient past and relying on cultural traditions that have sustained them over centuries. MHA Nation’s organized response to COVID-19 revolved around what the tribes recognize as their greatest strength — family.

No matter the challenge being faced, family is every community’s most valuable asset.

Could history dare repeat itself?

In a remote expanse of Indian country in North Dakota, where life tends to move at a leisurely clip, word of a deadly new coronavirus traveled quickly. Most everyone in MHA Nation had heard the story of the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic that nearly destroyed the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara, the nation’s three affiliated tribes.

a tribal nation’s pandemic response

Family strength

Building Communities of Hope | Creating a better future for children and families in a time of crisis

“If we can help [families] get to these resources, navigate these resources, that’s what we’re here to help do,” says Quality Assurance Analyst Nicole Harper. “It was so wonderful and refreshing, even my director made a few calls!”

All families have challenges to overcome. Michigan used data to identify the families at greatest risk of entering the child welfare system and offered those families resources to help them overcome some of their challenges. This work is bringing new light to the strength and resilience of so many families who are operating on the margins and might need a little extra help.

Michigan hopes to continue this effort, even as they see budget cuts looming, because through more work like this — work that honors the positive traits of families most at risk — we manifest the truth that we are all experiencing in the midst of this pandemic: families are our greatest asset.

– Michigan father

I'm so excited. I feel like I can parent my

son again.

By late May 2020, staff had reached 60% of the families. Reactions have been transformative, for both family and field worker. One father, at the start of a phone call, admitted he felt at wit’s end. After 45 minutes of sharing, honest discussion and connections to real supports, he said, “I’m so excited. I feel like I can parent my son again.” Another parent shared the grief of losing two family members to COVID-19 and, through a stream of tears, expressed both gratitude and amusement that the first outreach she’d received was from child protective services.

Staff charged with outreach were initially nervous about this new role and shedding their typical duties of investigation, but they quickly found joy and pride in their proactive and supportive role.

“I was initially a nay-sayer, I’ll admit. I figured that people don’t want to be bothered by DHHS,” says Stephanie Young, a quality assurance analyst who personally reached out to about 45 families. “But my fears didn’t happen at all. We were able to help them outside of our case related resources.... Everyone that we reached out to was pleasant. Appreciative.”

“We’re giving them a warm, real person on the other end of that phone line who can help connect them to necessary services and supports,” Chang shared. The reason: “We hope that will prevent children from having to come into the foster care system.”

Chang emphasizes that the system is likely already familiar with the families at greatest risk. “We know where these kids are,” she says. “We want to offer those families much more intensive services and support in hope that we can really prevent calls and actual incidents of abuse and neglect.”

Using existing data analysis, Children’s Services identified roughly 14,000 families at highest risk to begin this outreach. Some 350 staff volunteered as outreach field workers and were quickly trained and deployed to call each of the 14,000 families with the goal of offering support services.

Domestic violence, safety and substance abuse support

Childcare and child development resources

Clarity on housing orders (Executive Order 2020-54 froze most evictions and foreclosures) and connections to housing assistance

Clarity on expansion of unemployment offerings and community-based financial assistance

Connections to school meal pickup sites and to Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits

An outreach call to warmly and genuinely

inquire about household and family needs

CLICK ICON TO SEE MORE

Michigan Children’s Services called together many agencies and departments that serve children and families to ensure its families received services. While these resources cannot eliminate the challenges faced by families, Michigan is working to activate community supports and allow families and communities to weather challenges better together.

– JooYeun Chang, senior deputy director,

Michigan’s Children's Services

What we need to do is continue to move upstream and provide services to families who are at risk.

In Michigan, like in many states, calls to the child welfare hotline dropped by half when the coronavirus forced schools and other public spaces to close and limited contact with mandatory reporters, such as teachers.

Rather than waiting until schools reopen, JooYeun Chang saw the opportunity to work with families to better ensure that children are safe at home by providing supportive services during the crisis. “What we need to do is continue to move upstream and provide services to families who are at risk,” says Chang, senior deputy director of Michigan’s Children’s Services.

A concern shared by many — though not all — across the country is that systems will be overwhelmed by abuse and neglect reports when children return to classrooms. Michigan Children’s Services is working to do what it can to prevent that from happening. And in the process, the agency isn’t ever planning to return to “normal” operations.

Children’s Services sits within Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services and manages protective and adoption services throughout the state, along with the foster care system and juvenile justice programs. In the wake of COVID-19, it has developed a shared vision and is working alongside the state’s private providers and many other agencies and systems, including the Department of Public Health, Department of Education and the courts.

Aggregating resources from all of the above, Children’s Services took a proactive stance in delivering support and reached out directly to families — especially those families most at risk — with an important question: What do you need? We’re here to help.

Michigan reaches out to families

Each one of us is experiencing the health and economic crisis in different ways, and the renewed Black Lives Matter movement is shining light on something the child welfare system has long known: our experiences are disproportionately different depending on the color of our skin, with people of color most negatively affected. One thing that COVID-19 has made exceptionally clear is that all families have challenges to overcome and we all need extra support at times. In good times, many families have the resources they need — physical, emotional and financial — to deal with those challenges.

With all that we are experiencing today, more families need extra support. Many are seeking help, yet many more are struggling without an extended safety net. We find inspiration and examples of innovation across the nation from organizations that are breaking away from their typical roles in order to offer support and help families connect to community-based resources to keep them stable and their children safe and healthy.

More than ever, families are our greatest asset in assuring that children are safe and have what they need to thrive. Years of research, data and front-line experience have helped us to realize that the best way to keep children safe is to help the adults in their lives. We must put that knowledge into action now.

a tribal nation’s pandemic response

System pivots to support families – our greatest asset

Building Communities of Hope | Creating a better future for children and families in a time of crisis

At the same time, the centers are cost effective. In Alabama, an analysis of short- and long-term impacts shows that for every $1 invested in the Alabama Network of Family Resource Centers, the state receives $4.70 of immediate and long-term financial benefits.

Their value is clear to the head of the federal Children’s Bureau.

“When we talk about family resource centers, in my view, it really is the embodiment of the vision we have in the Children’s Bureau for strengthening families through primary prevention of child abuse and neglect, and through supporting communities to actually support families,” said Jerry Milner, Children’s Bureau associate commissioner, during the May briefing hosted by NFSN. “Both family and community are absolutely essential in our society, and in our view, it’s time in child welfare we started acting like it and started funding those programs and supporting them and promoting them as our best hope of protecting children, strengthening children by strengthening their families.”

“We’re much better about responding to reports of child abuse and neglect as a system than we are at supporting families before those reports ever become necessary,” the commissioner said. “If we had throughout our country an integrated system of community-based supports for all families, such as family resource center networks and family strengthening networks, it could alleviate much of the stress that our families are experiencing now.”

– Jerry Milner, Associate Commissioner, Children’s Bureau

Both family and community are absolutely essential in our society...our best hope of protecting children, strengthening children by strengthening their families.

in parents’ self-reports on their ability to keep the children in their care safe from abuse in Massachusetts

20 percent increase

Statistically significant gains in family self-sufficiency in Colorado

Increased Family

Self-Sufficiency

Significantly lower rates of child maltreatment investigations in communities with FRCs in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

Lower Rates of Investigations

in cases of child abuse and neglect in Alachua County, Florida

45 PERCENT

REDUCTION

Research on family resource centers shows:

9:09 | In San Francisco, families who face multiple challenges have places where they can find help, right in their own neighborhoods.

11:35 | Gainesville, Florida, is building Communities of Hope through three community resource centers serving at-risk communities.

In California, the approach is so effective that Gov. Gavin Newsom earmarked $3 million in emergency funding in 2020, knowing that the nearly 1,000 family resource centers across the state are filling critical roles during the pandemic.

California isn’t alone in recognizing their importance. Family resource centers elsewhere are receiving increased state funding. In May, during a National Family Support Network national briefing, Alabama announced it was adding family resource centers as a line item into its state budget for the first time. The state’s 16 existing and five emerging family resource centers will receive $1.5 million total for the next fiscal year — $75,000 each.

Family resource centers provide families supports, services and opportunities, including community dinners, parent-child play groups, food and diapers, financial education and parenting classes, support groups and family counseling, leadership development and navigating housing or utility bills. By lending a hand with the essentials, FRCs keep the most essential thing intact; the family unit stays stable and resilient, and the likelihood of child neglect or abuse goes down.

– Andrew Russo, co-founder and director,

national Family Support Network

FRCs are on the front lines...supporting families to be healthy and strong, and decreasing their isolation and ensuring they connect with resources when they are struggling and challenged more than ever.

We trust our family members, our closest friends and our neighbors to help us out when we need a hand or a listening ear. It’s natural to ask for support from someone who understands us. Across the country, more than 3,000 nonprofit organizations called family resource centers (FRCs) also work to fill that role, welcoming 2 million people each year in community- or school-based hubs of support, services and opportunities for families. The core of this support is historically focused on strengthening families as a unit, within communities. The approach is strengths-based and family-centered.

During the economic and health crises created by COVID-19, these centers are lifelines. “Family resource centers across the country have continued to operate even when almost everything else shut down,” says Andrew Russo, co-founder and director of the National Family Support Network (NFSN).

“FRCs are on the front lines of supporting families through the pandemic,” Russo said. “And all of them across the country are still operational, supporting families to be healthy and strong, decreasing their isolation and ensuring they connect with resources when they are struggling and challenged more than ever.” Ultimately, these family resource centers are working to keep families stable and children safe and protected from abuse and neglect.

Family resource centers

provide help and hope

CONNECT

• • •

Early in 2020, but before the coronavirus pandemic changed the lives of most families, San Diego County’s Child Welfare Services (CWS) agency began rolling out an innovative partnership with their local United Way helpline.

United Way has been supporting 211 call centers since 1997, and they’re now available to nearly all of the U.S. population. Critical in times of disaster, the call centers have a large toolkit of referral resources for essential needs.

While some child welfare agencies refer families to seek assistance from 211, San Diego’s program is more hands-on. Under a new partnership, called 211 CONNECT, Child Welfare Services assesses hotline reports that were evaluated out, meaning no further investigation was warranted. CWS then refers some of these families to specially trained navigation specialists at 211 CONNECT. The specialists contact the families to offer support and connection to community resources. If the family agrees to participate in the program, 211 CONNECT navigation specialists talk with them, make referrals and check in regularly to see if they are getting the help they need.

The timing of this partnership was fortuitous, since the families that are referred are exactly the ones who are likely to need extra support during a pandemic. From January 2020, when the program began, to mid-June, CWS referred 140 families to 211 CONNECT, about 17% of whom enrolled. One father, for example, was part of 211 CONNECT before the pandemic. When he lost his job, he called back to get additional help finding resources for food and housing.

San Diego is also partnering with schools and school-based community providers to reach families where students are struggling. If a child does not log onto a device and is marked absent, for example, it may trigger an educational neglect report in some jurisdictions, but it could just as easily mean the child does not have a tablet or computer, does not have access to the internet, or that the caregiver doesn’t speak English or know how to instruct the child or reach the teacher. Finding a way to help these families without involving CWS benefits both the family and the agency.

To facilitate this process, San Diego schools bypass CWS, giving information directly to community providers, many of which already know the students. The schools identify the children they are concerned about and who have not checked in online. The providers then do wellness checks with those families, assessing needs and connecting the families to resources.

Making the connection with families

SAN DIEGO COUNTY

By design, the promotional materials for the helplines in Connecticut and New Hampshire do not highlight the role of the child welfare agency. And agency staff do not take the calls. Leaders believe parents or caregivers are more likely to seek help from a community provider or a state support line than from child protective services, which can be seen as a threat.

Using call lines aimed at families under stress, Connecticut, New Hampshire and San Diego [see below] are finding new ways to reach vulnerable families in challenging times. The free helplines offer a sympathetic ear, in multiple languages, and much more.

As this approach grows, leaders see potential for the future. What if more families could access warmlines to get the services they need, when they need them? What if mandatory reporters, school personnel, medical providers and law enforcement officials connected families to helplines before calling a formal child abuse hotline? This shift could make a critical difference to families and children, giving them the support they need to stay together safely. And it would save scarce government resources for families that really need them.

In crisis comes opportunity. Connecticut, New Hampshire and San Diego are accepting the challenge.

– JooYeun Chang, senior deputy director, Michigan’s Children’s Services

Leaders believe parents or caregivers are more likely to seek help from a community provider or a state support line.

In New Hampshire, the state Division for Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) is collaborating with Waypoint, a community provider, on what they call the Family Support Warm Line. “Callers may need advice or just a trusted, nonjudgmental ear,” says the website. Each call can last up to an hour and family support professionals provide guidance and support “on issues big or small,” as well as referrals. After the initial call, professionals follow up to see how families are doing and if they have engaged with the suggested referrals.

New Hampshire’s DCYF had already been working on front-end reform before COVID-19 struck, trying to reduce the number of families at low risk for entering the child welfare system who were being screened in for child welfare investigations, and deepening the agency’s community engagement efforts to help families and keep children safe without entering the system. Officials saw the health crisis as an opportunity to accelerate this effort, and the Waypoint helpline partnership is one part of their strategy. In April and June, the warm line received 86 calls, with more than 65% seeking support, including housing assistance. Waypoint hopes to continue the warm line after the pandemic, because it serves as a good source of referrals for its home visiting and parent skills programs.

PSA :30 | TalkItOutCT provides families a connection for support and resources. Courtesy of Connecticut Department of Children and Families.

Connecticut is among states working to reach families who, by getting help now during the pandemic, might avoid crisis referrals to the child welfare system later.

“All communities need help right now and we must recognize the additional stress and impact these times present to communities of color,” said Commissioner Vannessa Dorantes, of Connecticut’s Department of Children and Families, on the launch of the TalkItOutCT helpline. “This support line will further increase a family’s inherent strengths while offering timely support during these periods of uncertainty.”

“When it builds up, talk it out.”

That’s the simple message of a public service ad in Connecticut aimed at parents and caregivers. The ad launched the state’s “Talk It Out” line in April 2020, as Americans were deeply feeling the impact of COVID-19. It promotes an old-fashioned way for families to get help: the telephone. “If it ever gets to be too much to take, take a step back and take out your phone,” says the ad. “We’re here to listen, to understand and to talk your feelings out.” And while they’re listening, the trained professionals who answer the phone offer concrete support, advice and referrals to help parents, caregivers and children cope in these uncertain economic and emotional times.

Talking it out:

More than a shoulder to lean on

Child welfare leaders have been examining how hotline calls, investigative outcomes and child removals changed as the epidemic stretched into the summer — were they still reaching the right children and families, despite the decreased calls?

In San Diego County, hotline calls dropped to about half their typical volume, says Kim Giardina, Child Welfare Services director for the county’s Health and Human Services agency. But the number of petitions filed to take custody of children and possibly remove them from their parents remained steady.

“So we’ve been having this conversation: Do we need all these hotline calls to come back?” she says. “If we are still filing on the same number of kids, does that mean we are still getting the right families with the right level of intervention?”

With many schools planning to continue remote learning when the new school year starts, Giardina says she isn’t sure a much-talked-about surge of hotline calls will emerge. In the meantime, the department is continuing pre-COVID efforts to proactively connect with families to provide support, making use of federal coronavirus relief funding.

Community service providers that already partner with schools — and that families see as less threatening than child protective services — are checking in with families to see what they need. If a child hasn’t connected through distance learning, it could be they need WiFi or a laptop, or the family can’t pay its utility bills. Providers work to fill that gap.

“So, does that change how our community thinks about who they need to call, and could it be a way to permanently shift the way our system thinks about families in need?” she says.

Joseph Ribsam, director of New Hampshire’s Division of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF), shares similar thoughts.

Our success responding to, and emerging from, the threat of COVID-19 requires us to build on what we know works best to support the safety and well-being of children and families. Our foremost priority is to ensure families have the services and supports they need to keep children safe. That is why we must work intentionally to connect with families when the typical places that we see children — schools, doctors’ offices, houses of worship — are closed.

Building on what

we know works best

Building Communities of Hope | Creating a better future for children and families in a time of crisis

Family Resource CenterS

San Diego County

Talking it out

JUMP DIRECTLY TO LEARN MORE ABOUT:

13:18 | Innovation in Texas: Watch a demonstration of simultaneous translation in virtual court proceedings. Courtesy of Supreme Court of Texas Children’s Commission.

One concern, though, has been the rawness that a virtual venue can pose. An 18-year-old mother, for example, was sitting all alone in her car when her judge, via Zoom, ordered termination of parental rights. One of the most devastating outcomes in child welfare, the action separates a child from their parents and, potentially, their relatives, history and culture. The young mother in this case began crying uncontrollably. In a courtroom, that mother would have been surrounded by people who could offer her support and keep her safe, said Paula Bibbs-Samuels, a commissioner who serves as a parent representative on the Children’s Commission.

“If you did a poll of parents, I bet they would rather a judge tell them that kind of thing face-to-face vs. over Zoom,” Bibbs-Samuels said. “I know I would.”

At the same time, the virtual platform is increasing access for parents and other parties who otherwise would not have been able to attend in-person hearings — for example, birth parents who are incarcerated or youth living in restrictive settings. A father who had a warrant out for his arrest — and never would have shown up at the courthouse — participated in a recent hearing via Zoom to offer meaningful information in his child’s case. Another father who had been absent from all previous hearings regarding his child showed up for the first time to testify via Zoom. For families not fluent in English, the switch to virtual hearings has meant easier access to interpreters, who quickly can be called into service no matter where they live.

– Judge Melissa DeGerolami, Child Protection CourT,

South Central Texas

A lot of times, I don’t physically lay eyes on a young child whose case I am deciding because the child isn’t brought to court. Now, I might see a toddler running around, coming in and out of the screen. I can witness their level of comfort with their surroundings and with their caregiver.

When Texas went under COVID-19 lockdown, the Supreme Court of Texas Children’s Commission clicked into action by supplying information to judges and attorneys on how to prepare for the move to virtual hearings and how to use a virtual video platform, said Texas District Court Judge Rob Hofmann, a Children’s Commission jurist in residence. Initial concerns were raised about whether virtual hearings would limit participation of people who are low-income or from marginalized communities, and who might not have access to the video platform or strong Wi-Fi connections. But Judge Hofmann said he has “yet to hear of a person say they couldn’t appear via Zoom, at least through the app on their phone. The benefits of people being able to participate under their own conditions, usually from their own home, are outweighing the concerns we had about people not having access. Yes, we’ve had a few technical glitches. But people have been very gracious and very patient — especially parents.”

– Judge Darlene Byrne, Travis County District Court

Childhoods fly by. We can’t put a child, whose life is languishing, on hold.

That’s not right.

“We couldn’t stand by and say, ‘Well, since we can’t have in-person hearings, we’re just going to wait,’” said Travis County District Court Judge Darlene Byrne, who began setting up virtual processes for her family court in Austin even before the stay-at-home order became official. “Childhoods fly by. We can’t put a child, whose life is languishing, on hold. That’s not right.”

Although data is not yet available to show the effect of virtual hearings on permanency rates, anecdotal evidence is as vast as the state of Texas itself. Several judges and attorneys say that birth parents, youth, kinship caregivers and foster parents are more engaged with virtual court hearings. It’s no surprise that older youth, so comfortable with video chatting and other virtual communication, are more involved. Judges also are upping youth engagement by using Zoom breakout rooms for private side conferences, providing a safe space for them to share critical details they otherwise might never be comfortable disclosing.

Judges say the visual cues they get from Zoom are helping them make more informed decisions. One parent, for example, convinced Judge Byrne that her home was safe for reunification with her child by giving the judge a real-time video tour of the baby nursery she had just set up, complete with safety covers over the electrical outlets. Out-of-area placements also are giving judges virtual tours of their homes as evidence to help with decisions.

Two brothers and a sister, living with their grandmother over the past four months, expressed reluctance about starting formal visits with their mother. The children had been removed from her and their stepfather due to violence and drug use in the family home. So Texas Associate Judge Melissa DeGerolami, who had issued that removal order, scheduled her own visit with the two older children — a virtual one that looked much different than before COVID-19 upended family courts across the country.

“We needed to get working toward healing this family,” said Judge DeGerolami, who presides over the Child Protection Court of South Central Texas. Speaking via Zoom from the comfort of their grandmother’s home instead of within the intimidating walls of a courthouse, the older brother and the sister began opening up to the idea of visitation.

“We talked about their comfort level in starting visits with their mother,” Judge DeGerolami said. “Over the course of our extended conversation, they told me Mom had sent them Easter baskets and how they really appreciated that. Eventually they said, ‘I think we could,’ and I was able to order that the visits get started. I’m not sure we would have reached that same place had our conversation occurred in a courtroom, even in judge’s chambers.”

Dictated by the pandemic to rapidly shift course, Texas family courts have led the way in using real-time video conferencing in lieu of in-person hearings, avoiding case backlogs and keeping children and families on a timely path toward permanency and reunification. The result, several judges say, is a more flexible, accessible and responsive system, offering lessons that can be followed after courthouses reopen.

Virtual court proceedings make

real connections for Texas families

COVID-19 has made it clear that we must act with urgency to ensure every child in foster care has a safe, strong and permanent family, and to provide families with the support they need to succeed. To make sure that no child lingers in a temporary home or institution, and that no youth ages out of the system without caring adults in their lives to provide support and guidance, Casey Family Programs, child welfare systems, national partner organizations and communities are working relentlessly — often with the help of technology — to bring families together.

Virtual Adoption Video

ONLINE TRANSLATION VIDEO

Virtual Court

JUMP DIRECTLY TO LEARN MORE About:

Every child deserves a

safe, strong and permanent family

Building Communities of Hope | Creating a better future for children and families in a time of crisis

Constituent voices

Victoria is a member of Generations United's GRAND Voices Network, a select group of grandparents and other relative caregivers serving as strategic partners to inform policies and practices affecting kinship families, also known as grandfamilies. She has also earned awards and recognition for her role as a voice for kinship caregivers. In 2017 she received the Brookdale Foundation Grandfamilies Award from Generations United, in 2019 she received a special commendation from the first lady of Arizona for her work advocating on behalf of kinship families and in 2020 she received a Casey Excellence for Children Award from Casey Family Programs.

Victoria emphasizes: “Kinship care is worth it because it provides the care and love only a family can provide. But it requires time and attention and resources for the families taking that on.”

Additionally, these grandparents are

Of these grandparents

grandparents are householders responsible for their grandchildren who live with them.

2.7 million

children live in households headed by grandparents or other relatives

7.8 million

Kinship families, also known as grandfamilies, are families in which children live with and are being raised by grandparents, other extended family members and adults with whom they have a close family-like relationship, such as godparents and close family friends.

Kinship care in the united States

Like the families she works with, Victoria finds herself spending more time running her household, which includes seven grandchildren and great-grandchildren, ages 1 to 17. To feed a family of nine and reduce exposure to COVID-19, Victoria and her husband, Gentry, have had to get creative by shopping separately at multiple stores during special hours set aside for people over 65, checking in with each other via cell phone to find out which store has toilet paper and cleaning supplies.

She hears from other grandparents who share the challenge of caring for small children all day since schools are closed. “Some admit to going without their medication and enduring more pain because the medication makes them sleepy,” she explains. Accessing or navigating technology for remote learning poses a learning curve (her grandchildren help her set up online video calls). Then there’s the added concern of health risks when schools eventually do reopen.

“Lots of other grandparents are worried,” she says. “I’m not the only one that’s expressing the worry about how soon is too soon to reopen?”

Layered on top is the tension of continuous news coverage as the country confronts its history of racism. “Television is hard to watch these days,” says Victoria, who is African American, adding that some families have called her to say their grandchildren are affected by it, reminded of violence they experienced with their parents.

While Victoria worries that the isolation and added stress from social distancing is taking a toll on families, she is hopeful things will improve soon. If nothing else, the pandemic has underscored the importance of personal interactions and relationships. She believes her work can still make a difference, and the key to keeping families together moving forward is to provide them with the support they need and a caring ear to listen.

00:46 | In light of national protests over the death of George Floyd, Victoria Gray reflects on how the child welfare system treats Black families.

Like the families she works with, Victoria finds herself spending more time running her household, which includes seven grandchildren and great-grandchildren, ages 1 to 17. To feed a family of nine and reduce exposure to COVID-19, Victoria and her husband, Gentry, have had to get creative by shopping separately at multiple stores during special hours set aside for people over 65 checking in with each other via cell phone to find out which store has toilet paper and cleaning supplies.

She hears from other grandparents who share the challenge of caring for small children all day since schools are closed. “Some admit to going without their medication and enduring more pain because the medication makes them sleepy,” she explains. Accessing or navigating technology for remote learning poses a learning curve (her grandchildren help her set up online video calls). Then there’s the added concern of health risks when schools eventually do reopen.

“Lots of other grandparents are worried,” she says. “I’m not the only one that’s expressing the worry about how soon is too soon to reopen?”

Victoria typically meets one-on-one with grandparents and other kinship caregivers to help them find resources and provide support during the first uncertain days and weeks of taking a child into their care. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, those face-to-face meetings have been replaced by phone and online video calls.

"These families feel like I'm on their side because I've been in their shoes and I've felt the emotions, stress and fear they are experiencing,” she explains. “I listen to them and help them understand how things work and how to get the things they need.”

5:32 | Victoria Gray, founder of the nonprofit GreyNickel, Inc., aids kinship families during the critical first days of a new placement. She is the winner of a 2020 Casey Excellence for Children Award.

Victoria Gray has decades of experience raising her seven grandchildren and 41 foster children as a licensed foster parent in Arizona. These days, she applies her experience in her work as a peer-to-peer mentor at GreyNickel, Inc., the nonprofit she founded, providing much needed support and guidance to kinship caregivers who are raising some of the 7.8 million children in America living in households headed by grandparents or other relatives.

Grandparents navigate unique challenges amid COVID-19

Listening to those closest to the system

"These playbooks are driving our response in Nebraska and provide an accurate read of day-to-day needs in the community," says Stephanie Beasley, director of Children and Family Services at the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services. "We are all working together and ensuring the right tools and resources are put in the hands of child welfare workers, educators, members of the community and the collaboratives."

Bring Up Nebraska, launched in 2017, is about community leaders and neighbors coming together to solve the challenges where they live. It is an example of investing existing resources more effectively to address the needs of families. Investment from private philanthropists combined with state treasury relief funds helped Community Response Collaboratives meet community needs such as helping families pay rent and utility bills, securing hotel and motel vouchers for homeless families and providing stipends and grocery gift cards to families not eligible for SNAP benefits. That this partnership could pivot quickly in a pandemic shows the power of relationships.

Skala says, “The collaborative infrastructure created in communities has proven to be an effective means of supporting families through disasters, as well as providing resources to keep families safe and healthy in the long term."

– Stephanie Beasley, Director of children and family services,

Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services

These playbooks are driving our response in Nebraska and provide an accurate read of day-to-day needs in the community.

• To help ensure children were able to continue their schoolwork remotely, the state's education department and Bring Up Nebraska community collaboratives worked with technology companies to bring internet and devices to families without access.

• New partnerships were formed with the United Way 211 and other housing providers to meet rental assistance needs.

• Bilingual central navigators and outreach workers were hired and a statewide community response phone number was established for Spanish translation.

Using information from the playbooks, state and local partners quickly coordinated to help families. Their efforts include:

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bring Up Nebraska worked with community response agencies to find out what was needed as schools closed and businesses shut down across the state. They compiled the information into “playbooks,” summarizing not only immediate needs in each community — food and childcare, for instance — but also uncovering issues and identifying gaps in services, such as adequate technology and devices to access the internet.

"We knew the best way to truly help communities during this pandemic was to understand their needs and then in partnership with state partners fully address them. We created this playbook process to initiate those conversations,” says Jennifer Skala, senior vice president of Nebraska Children and Families Foundation. “Every community across the state has its own unique challenges and we must listen and act to address them.”

Learn More

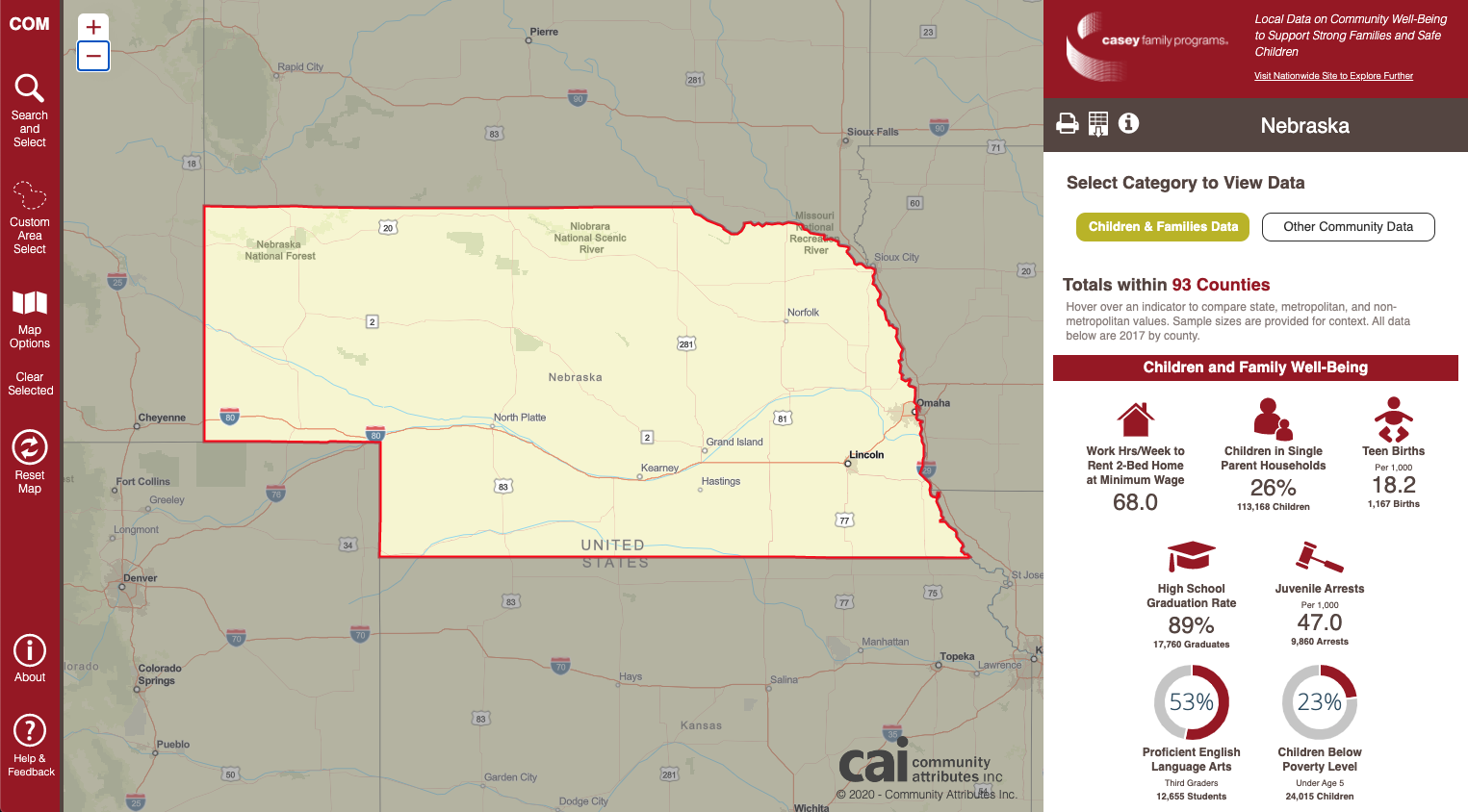

The Nebraska Children and Families Foundation and the strong network of organizations it partners with have long understood the value of using data to evaluate community conditions.

In 2019, Nebraska Children sought to further enhance the use and availability of data by developing its own Community Opportunity Map. Learn more about this effort:

Nebraska Community Opportunity Map

9:29 | Bring Up Nebraska coordinates existing resources within a community, enabling young adults and families to determine their own paths toward well-being goals.

Learn more about Bring Up Nebraska in this video story

When crisis hits, precious time is often lost mobilizing teams and developing response plans before relief can reach those who desperately need it. The state of Nebraska, however, was ready to move to support children and families when the COVID-19 outbreak emerged — already equipped with critical resource networks and people in place to quickly respond.

This response — battle-tested during 2019’s historic flooding that caused more than $1 billion in damage — was led by Bring Up Nebraska, a community-based partnership of organizations whose primary focus is identifying the needs of young adults and families in local communities and then pulling together resources to provide critical supports, services and collaborative solutions. All sectors of the community are at the table in this partnership — including young adults and parents, government agencies, philanthropic and community-based organizations, faith institutions and the business community — collaboratively taking ownership for meeting community needs. Casey Family Programs recognized this life-changing work with a 2020 Jim Casey Building Communities of Hope Award.

Bring Up Nebraska:

A game plan for resilience

The current health and economic crises, layered on top of centuries of systemic and institutionalized racism and inequity, display ever more clearly that it is past time to move from a child welfare system and instead invest our resources into a child and family well-being system that truly supports children, families and communities. These times call for bold steps forward and a much broader coalition of people and organizations in our neighborhoods to build up supports so our children are safe and families are strong. Systems across the country are looking at what they have had to “turn off” during the pandemic, and what they can keep turned off as states reopen. They’re also considering what innovative practices they should keep. In some cases, strong systems were already primed to support families, and that work has only grown stronger.

Listening to Constituents

BRING UP NEBRASKA

JUMP DIRECTLY TO THESE STORIES:

From child welfare to

child and family well-being

Building Communities of Hope | Creating a better future for children and families in a time of crisis

2,172,876,720

$

ALASKA

10,102,422,624

$

ALABAMA

SUBSTANTIATED CASES, 2018

Lifetime Economic Burden

830,928

$

INFANT

ADULTHOOD

Estimated cost of non-fatal child maltreatment

Over the course of a child’s lifetime

Tangible costs such as

Intangible costs such as

This includes

MEDICAL CARE

SPECIAL EDUCATION

CRIMINAL JUSTICE

PAIN AND SUFFERING EXPERIENCED BY THE CHILD AND THE BROADER COMUNITY

220

$

MILLION

PER DAY

That's more money per year than it would take to end hunger in the united states.

Cost per state

Cost per child

Cost Per day

Although cost savings offer compelling evidence of the effectiveness of prevention programs, monetary benefits alone should not be the primary driver of decisions to implement them. Involvement with the child protection system (CPS) is traumatic for children and families, and society has a moral and ethical obligation to protect families from the unnecessary intervention of CPS and ensure the availability of services and supports that strengthen all families.

CLICK ON THE BUTTONS TO LEARN MORE

Child maltreatment is costly

Budgets — from federal to family — have been decimated this year. In prioritizing spending for the future as communities and systems reopen and rebuild, leaders at all levels must incorporate the lessons learned during this crisis. Support for youth and families is a sound investment.

We face a stark choice. In cities, counties, tribes and statehouses, policymakers will be debating how to balance budgets and address the vast challenges facing our communities. This is an opportunity to reallocate those resources in hope-inspiring supports for families that prevent abuse and neglect, reduce the need for foster care and build the supports that children and families need to achieve well-being.

Learn More ABOUT INVESTING UPSTREAM

Research estimates that for every $1 spent on Family Assessment Response, agencies can save $6.80.

FOR EVERY DOLLAR SPENT ON FAMILY ASSESSMENT RESPONSE

AGENCIES CAN SAVE OVER $6

Family assessment Response

Family Assessment Response

Family Assessment

In Vermont, resources that keep children from entering foster care save the state an estimated $210,000 per family that would otherwise experience adverse childhood experiences.

PER FAMILY

210,000

$

ESTIMATED SAVINGS

Vermont

Vermont

Alabama has seen a benefit-cost ratio of $4.70 for every $1 spent on its Family Resource Centers, with a particularly strong impact for its parenting centers.

Benefit-cost ratio of $4.70 for every $1

1

:

4

MORE THAN

Alabama

Alabama

Family Resource Centers

For Functional Family Therapy, overall savings for court-involved youth were estimated to be $7,098 per youth, with $2.76 saved for every $1 spent.

OVERALL SAVINGS OF OVER

PER CHILD

THOUSAND

7,000

$

FUNCTIONAL FAMILY

FUNCTIONAL FAMILY

A review of studies on Parent-Child Interaction Therapy found savings

of $22,994 per family in the child welfare system, and a benefit-cost ratio of $15 for every $1 spent.

22,000

$

THOUSAND

PER FAMILY

SAVINGS OF OVER

Parent-child Interaction

Parent-child interaction

Therapy

Statewide implementation of the Nurturing Parenting Program for child welfare-involved families in Louisiana resulted in a conservatively calculated benefit-cost ratio of .87 (approaching cost neutrality) due to reductions in both repeat maltreatment reports and incidents of substantiated maltreatment. Study authors expect that the benefit-cost ratio would increase if the program were delivered to a more targeted population and if outcomes were tracked over a longer period of time.

87

BENEFIT-COST RATIO

.

Nurturing Parenting Program

Nurturing Parenting Program

The Washington State Institute for Public Policy found a benefit-cost ratio of $9.71 for every $1.00 invested in the Triple P Positive Parenting Program, a universal prevention program.

1

:

9

APPROXIMATELY

BENEFIT

COST RATIO

Triple P

TRIPLE P

The Washington State Institute for Public Policy found a

benefit-cost ratio of $5.65 for every $1.00 invested in

Incredible Years parent training.

$5.65

$1.00

Incredible Years

Incredible YEars

Parent training

The Perry Preschool Project resulted in a $12.90 return on investment per $1 invested, due to savings in education spending, welfare spending, criminal justice spending, and increased taxes on income.

RETURN FOR EVERY $1 INVESTED

ALMOST A

13.00

$

PERRY PRESCHOOL PROJECT

PERRY PRESCHOOL PROJECT

Cost-benefit analyses from the Centers for Disease Control estimated that nationwide implementation of Child-Parent Centers (preschool + school age) could save $16.9 billion and nationwide implementation of Child-Parent Centers (preschool only) could save $10.4 billion in societal costs over the lifetime for each annual cohort of children.

27

BILLION DOLLARS

Savings over

CHILD-PARENT CENTERS

CHILD-PARENT CENTERS

A nationally representative sample of children ages 0 to 5 found that children placed in Early Head Start (prenatal to age 2) or Head Start

(age 3 to 5) were 93% less likely to enter foster care, compared to children who received no early childhood education.

Less likely to enter care

%

93

Head Start

Head Start

Early care and education programs have numerous demonstrated cost savings.

Early care and education

SafeCare, a home visiting program for at-risk children and families, provides $20.80 in benefits for every $1.00 spent.

$1

$20

Every dollar spent

Provides $20.80 in benefits

SafeCare

SafeCare

Nationwide implementation of Nurse-Family Partnership

child home visiting could save $16.0 billion over the lifetime of each annual cohort of participating children.

IN SAVINGS

BILLION

16

$

NURSE-FAMILY PARTNERSHIP

NURSE-FAMILY PARTNERSHIP

A randomized control trial of Family Connects home visiting showed

that families receiving the intervention had 44% fewer child maltreatment investigations.

44

%

FAMILY CONNECTS

FAMILY CONNECTS

HOME VISITING

CLICK ON THE ICONS TO LEARN MORE

But there is something we can do: direct investments in social programs for children demonstrate high returns in both the short and longer term. Tangible benefits show up in their health and well-being, as well as in money saved by avoiding the costly results of child maltreatment.

Prevention programs that result in real returns

The health and economic disasters of COVID-19 and the visceral pain of systemic racism require us to examine how we treat each other. The Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018 creates new opportunities for us to implement innovative approaches that keep our children safe and our families strong. Many communities have already stepped up, showing what can be done. Direct investments in social programs for children demonstrate high returns in both the short and longer term.

Investing in hope

A CAll to action:

Building Communities of Hope | Creating a better future for children and families in a time of crisis

No longer are attorneys meeting and conferring with their clients for the first time in the hallway outside of a courtroom. Attorneys also have lost the luxury of whispering instructions into the ear of a client while a hearing is in progress, meaning they have to get their parent clients more prepared, as well. Attorneys advise them that even though it’s a virtual hearing, the formality and rules of a courtroom still apply. Proper dress. Don’t chew gum. No downward glances to check your phone. Turn off the TV. Send the dog to the other room.

Judge Byrne works hard to put parents and youth at ease in the virtual setting. She once went as far as to change her virtual background to a big field of balloons at the exact moment she informed parents that their two years of hard work had paid off and she was — at long last — dismissing their case. They celebrated together, as if they were in the same room.

10:35 | In the wake of current social distancing measures, connecting digitally has become a priority for many. In April 2020, technology helped complete a forever family when the Smiths met with attorneys, Buckner International and a Lubbock County judge on a Zoom conference call to complete their adoption of 15-month-old Khailynn.

“The Zoom platform has allowed many more people to participate in hearings,” Judge Byrne said. “There are fewer boundaries.”

Parents from California, Mexico, and as far away as Liberia are calling in to participate, sometimes resulting in emotional moments as a parent sees a child — albeit on screen — for the first time in a long time. Foster parents who might have struggled to participate at a courthouse now log onto Zoom at the designated hearing time, knowing that virtual dockets tend to play out on time, free of the delays common to in-person proceedings.

Judge DeGerolami said being able to set exact times for hearings has been a real benefit in her jurisdiction, which is spread out among five rural counties south of San Antonio. Commute times and the limited availability of courtroom space have always made her docket a logistical challenge, now made easier through Zoom.

“By setting specific time frames for hearings, people know exactly when their case is going to be called and they are ready to go, as am I,” she said. “It’s so refreshing to not have to sit and wait for an attorney from another county who is running behind, or for a child to show up who is two hours away. I'm now able to hear cases quicker, and that really amounts to better permanency for children and families in my court.”

To comply with the open courts doctrine in Texas, the Zoom hearings are streamed live on YouTube and available for anyone to view. The transparency is putting both judges and attorneys on the spot as their performances are put on display for all to critique. Several attorneys said in a recent Children’s Commission webcast that going virtual has required them to spend more time preparing for hearings — as much as 50% more.

Supporting Families Through:

• Working with the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the state expanded access to federal school lunch programs, allowing schools to deliver thousands of meals to students even though they were not attending classes.

• The state partnered with the USDA to help Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients reduce their risk of exposure to COVID-19 by letting them order groceries online from Amazon and pay with their electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards.

• To further address food insecurity, the Department of Health and Human Services worked with the community collaboratives and schools to enroll families in a new Pandemic EBT program.

• Bring Up Nebraska recently launched the Nebraska Child Care Referral Network, an online database matching essential workers to openings in licensed child care centers. The state is also offering grants to child care providers who offer low-income families discounted child care services.

EVERY CHILD COUNTS

Across the United States, about 424,000 youth under age 18 live in foster care. A disproportionate number of them are from families of color.

Learn More

In 2018, approximately 3.5 million children were involved in an investigation or alternative response for maltreatment. Rather than waiting for harm to occur, we can create a child and family well-being system that prevents abuse and neglect and helps every child grow up safely in his or her own family whenever possible. We believe that by working together, we can create a nation where Communities of Hope provide the support and opportunities that children and families need to thrive. Learn more about children in care in your state.

Why should we bring a racial equity lens to our work with children and families?

SCROLL

Download Well-Being Guide

Learn more About Helplines

LEARN MORE ABOUT FRCs

Learn More

Any court hearing that progresses the case toward permanency is essential to that child and family.

VIRTUAL HEARINGS

“A lot of times, I don’t physically lay eyes on a young child whose case I am deciding because the child isn’t brought to court,” Judge DeGerolami said. “Now, I might see a toddler running around, coming in and out of the screen. I can witness their level of comfort with their surroundings and with their caregiver. Even with very young children, they may not be able to tell me things, but they are showing me things. It’s revelatory.”

We believe forward-thinking, innovative leaders must work in partnership across a variety of sectors to create a 21st century child welfare system that invests in population-based prevention strategies for families most at risk of becoming involved with child welfare.

Learn More

We hope the stories in this report have inspired you as we work together to create a better future for children and families. Explore these resources to support your efforts.

RESOURCES

Building Communities of Hope | Creating a better future for children and families in a time of crisis

Investing

In Hope

7

7

Child and family

well-being

6

6

Permanent Families

5

5

What is

working

4

4

SUPPORTING FAMILIES

3

3

Tribal Family Strength

2

2

LETTER FROM PRESIDENT AND CEO

1

1

21st Century Transformation

Learn More

In today’s public health crisis, it is important to provide community-based services to all families and instill a collective sense of responsibility for the well-being of all children.

Supporting Families

Learn More

We continue to work with others in our commitment to anti-racism, anti-discrimination and equity, fiercely motivated by our belief in the intrinsic dignity and value of every person.

Racial Equity

Learn More

We know that separation from parents can be traumatic for a child. During COVID-19, virtual hearings have surfaced as a viable strategy to minimize delays and ensure that due process rights of children and families are protected.

Courts

Learn More

Voices of children, youth and families are both essential and critical to all aspects of child-welfare planning and decision making.

Constituent Engagement

Learn More

Kinship navigator programs provide much needed support for grandparents and other relative caregivers to learn about, locate and use support services to meet the needs of the children they are raising.

Kinship Caregivers

Learn More

Understanding the effects of foster care on children is key to building effective solutions that will have long-term, positive impacts in helping foster youth build successful adult lives.

Foster Care Outcomes

How is a 21st century child well-being system better for families and communities?