For years, critics have accused index funds of mechanically buying stocks no matter how much they go up. Now the naysayers have a new critique: Index funds can also mechanically buy stocks no matter how much they go down.

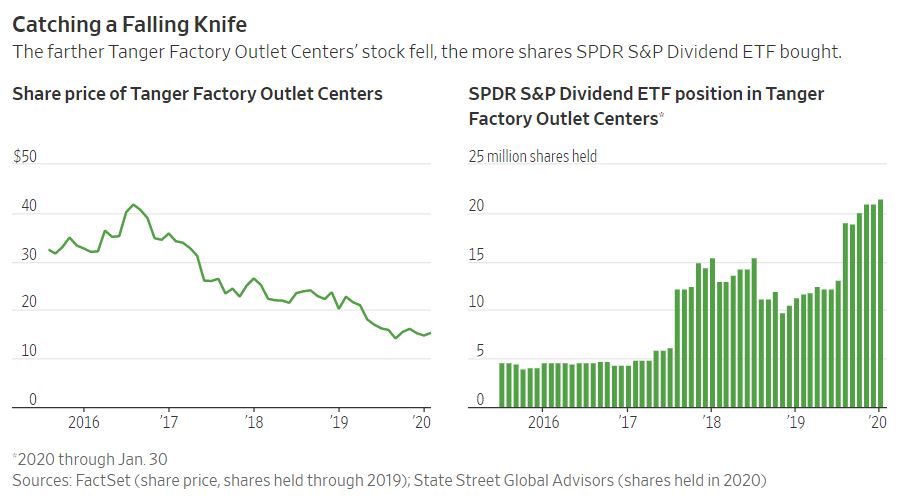

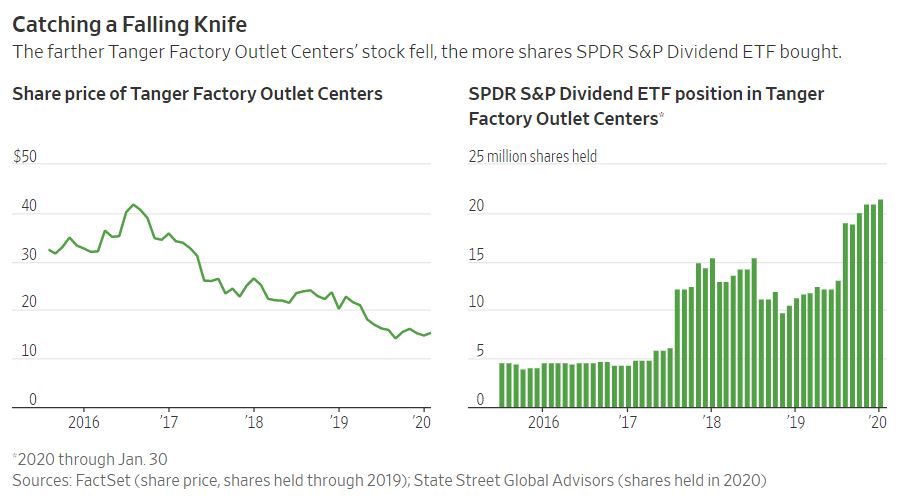

Consider the strange situation at the SPDR S&P Dividend exchange-traded fund (SDY), with $20.6 billion in assets. Over the past three years, the ETF nearly quintupled its holdings in Tanger Factory Outlet Centers Inc. (SKT) —even as shares in the shopping-property owner fell nearly 60%. By the end of 2019 the fund owned an immense 22.6% of Tanger’s stock. (Other ETFs held another 20%.)

Now that Tanger’s stock has halved, the fund has to sell. Short sellers, who bet on falling prices, smell blood and have been swarming Tanger. The shares slumped 10% in two days in late January on record volume, then bounced back.

The story behind these events is far from an indictment of indexing. It’s a reminder, first, of how diversification protects against unexpected market moves. It also offers a warning of how important it is for index-fund investors to understand what they own.

Consider first that indexes and the funds that track them aren’t one and the same. The S&P High Yield Dividend Aristocrats index is a basket of more than 100 large and mid-sized companies that have raised their dividends at least 20 years in a row. The SPDR S&P Dividend ETF seeks to replicate the return of that basket.

The next wrinkle is how an index is constituted. Typically, the greater a stock’s market value, the bigger its representation in an index—and in any funds tracking that benchmark. The High Yield Dividend Aristocrats index, however, holds stocks in proportion to their dividend yield.

So the higher a company’s dividend relative to its stock price, the bigger its position in the index. That can happen in two basic ways: The dividend can go up (yay), or the stock can go down (uh-oh).

Imagine a company with a share price of $10 that pays $1 in dividends per year. Its dividend yield is 10% ($1 divided by $10). Let’s say the stock price falls by half while the dividend holds steady. Now its yield has doubled to 20% (the dividend of $1 divided by the $5 share price). So the index and any funds tracking it will double their holdings.

The diversification rules of the

aristocrats index limit such changes.

No stock can make up more than 4%

of the index (or the ETF), for example.

But the companies in the index must

also maintain at least $1.5 billion in

market value at year end.

Because Tanger and Meredith Corp.

(MDP), the media company, have sunk below that, S&P Dow Jones Indices will boot them from the aristocrats list after the market close on Jan. 31.

When index funds buy a falling stock en masse as dividend yields rise, “that’s an unintended byproduct” of the focus on high-yielding companies, says Aye Soe, global head of product management at S&P Dow Jones Indices. “But it would be a very ad-hoc decision for us to change the rules of the index as a result.”

The power of diversification limited the damage from the collapse in Tanger and Meredith’s share prices. Although the ETF bought boatloads of both companies’ stock last year, that reduced its total return by only about 0.8 percentage points, according to State Street Global Advisors, which runs the fund.

That’s because neither of the two companies even hit the 4% limit set by S&P Dow Jones Indices. The ETF’s combined holdings in Tanger and Meredith are less than 3% of its assets, so the fund still returned 23.3% in 2019. Thus far this year, the net contribution to yield and total return from the two stocks has been flat.

Matthew Bartolini, head of ETF research at State Street Global Advisors, points out that the dividend fund has “delivered really consistent, superior returns,” outperforming 94% of all large-company value funds since it launched in 2005.

Although the fund does have to sell all its Tanger and Meredith shares, Mr. Bartolini says, the ETF can take its time and won’t tip its hand on how and when it will sell.

“How we get there is something we will keep inside our walls,” he says. According to the fund’s daily disclosures, it bought—not sold—more than 720,000 Tanger shares between Jan. 27 and Jan. 30 as investors added more money to the ETF. So far this year, Tanger’s stock is up 6.2%, after falling 21.3% in 2019.

Big technology stocks such as Facebook Inc. (FB), Amazon.com Inc. (AMZN), Apple Inc. (AAPL) and Google’s parent Alphabet Inc. (GOOG) aren’t owned disproportionately by index funds, says Will Geisdorf, ETF strategist at Ned Davis Research, a Venice, Fla.-based investment firm. Instead, he says, ETFs are often the dominant holders in “small, boring stocks for yield-hunting investors” in sectors such as natural resources, real estate and utilities. ETFs own at least 20% of 77 such companies, according to Ned Davis.

That means that if investors keep piling into the narrower, more-specialized ETFs that traffic in these stocks, it may be only a matter of time before such a fund ends up owning a third, a half or even more of some company’s total shares. What happens with Tanger is a test case for what that kind of market might look like.

Wall Street Journal

5 big ETF trends to watch