Related Insights

Workforce 2025:

Power Shifts

Attracting Top

Talent: A Workplace Flexibility Checklist

World’s Most Admired Companies 2025: Rebels with a Plan

READ THE

FULL MAGAZINE

VIEW THE

PODCAST

n the surface, you might think a leadership expert like Ralph Gigliotti would have it pretty

easy with clients these days. After all, profits have been up for four quarters at big firms,

inflation is no longer the economic boogeyman, and more and more employees are

returning to the office.

But Gigliotti, who directs the Office of Organizational Leadership at Rutgers University, says that nearly every business leader he talks to these days shares a similar the “sky is falling” feeling. He started teaching a global leadership course in Singapore in May, and says his students, all mid- and senior level executives, complained about major disruptions piling up, and had one question: What do we do? “It does seem like crisis has become a near constant condition,” he says.

It’s no surprise to anyone in the C-suite that the world around them, along with all aspects of the business climate, keeps accelerating. And there isn’t a leader among them who isn’t used to dealing with each of the disruptions this fast pace brings. But experts say there is something decidedly different going on these days—namely, how so many setbacks keep happening at the same time. It’s easy to create a list of them: tariff announcements, closely followed by a massive plunge in the stock market. Firms pouring millions into AI, only to discover that a much cheaper version from China may become viable. Economists putting the chances of a US recession at 40 percent one week, then 80 percent the next. The war in Ukraine seemingly nearing an end, just as a conflict in Iran was making headlines.

From the standpoint of a corporate leader, how tough does this get? Mike Lawford, president and CEO �of the billion-dollar Canadian energy-production firm NuVista, says he is used to the tension that wild swings in energy prices can produce, but even he was thrown for a loop this spring when the trade war escalated and once rock-solid Canada-US relations took a turn. “It all hit the world all at the same time, and everyone was saying it’s all bad,” he says.

In such cases, experts say, leaders can wind up feeling disoriented and exhausted. That, in turn, leads �to bad decision-making. We decided to look at four key areas that leaders need to keep an eye on and adjust for during these times, from how to make critical supply-chain decisions, to managing people, to handling today’s political divide, even to adjusting their own temperament. For his part, Gigliotti says he and other leaders have little choice but to focus energy on areas they have the greatest control over. “Even when the broader context feels chaotic, that keeps us moving forward,” he says.

Leaders are trained to deal �with disruptions, but handling �them simultaneously creates �new challenges.

The problem

Wrong decisions can cripple �a company’s future.

why it matters

Leaders need to develop a �new temperament and redesign �strategies both for operations �and people management.

The solution

With so many crises now happening at once, �is a new breed of leadership needed?

Dazed and Confused

By Russell Pearlman / Illustrations by Tim Ames

Be ready to pivot.

Conditions turned quickly, but the best firms—and leaders—adapted to the circumstances. It wasn’t just getting people to work remotely, either. Leaders embraced new ways to manage, innovate, and inspire.

This spring, during a routine check-in with his manufacturing CEO client, the vendor noticed that the boss was distracted. The leader’s strategy had been upended by the new US tariff policies, impacting both the company’s day-to-day business and also a longer-term reorganization. Plus, he was getting pushback from investors over the firm’s quickly sinking stock price. The normally affable, open CEO was curt, irritable, even rude. “I felt really badly for him,” says the vendor, who asked not to be named to preserve his business relationship.�

Right now, CEO temperament is the topic of conversation in client calls, team meetings, and professional gatherings. Leadership coach Saara Haapanen was at a conference in April where the topic was ostensibly how HR departments could shape corporate culture, but the issue of how bosses are leading right now kept coming up. Managers, particularly senior-level ones, she says, are struggling because �they feel like they’re under assault. “Not everything is an emergency,” she says, “but when you’re being inundated it can be tough to figure what really is dangerous.” Indeed, Kevin Cashman, Korn Ferry’s vice chairman of CEO and enterprise leadership, agrees. “The general energy and hopefulness among leaders is low, and depressive feelings are so high,” he says.

When everything seems uncertain, it can be tempting for leaders to default to a more traditional so-called “directive,” or authoritative, approach to management. Do this. Do that. No dissent. It is a style that experts say can be valuable in the short term if everything is really on the brink. But today, many of the same experts say some perspective is in order. Even though it seems like everything is apocalyptic for the firm, it’s most likely not the case. Instead, most of today’s mounting disruptions boil down to difficult but manageable challenges around growth, expenses, technology, and people. Top bosses likely will find a combination of leadership styles—the ability to articulate a shared mission or the knack to generate consensus, for example—that will be more effective than just relying on the directive approach. “People don’t need more control; they need more clarity, care, and coaching,” Haapanen says.�

If leaders are finding themselves angry, afraid, or irritable, it can be valuable to turn to other leaders in their firm who may be feeling the same way. Pausing and identifying the emotion can help mitigate its impact and reduce stress, Haapanen says. “When a leader is grounded it helps the whole team feel steady,” she says. Most importantly, experts say, leaders should fall back on their sense of purpose and the purpose of the organization. By reminding teams, and themselves, why the work matters, leaders can not only reduce the fears of the uncertain environment, but also increase the motivation of employees.

STEER THEM DIRECTLY

BACK TO WHAT’S

IMPORTANT TO THEM

AND THEIR ORGANIZATION—

OTHERWISE, IT’S

LAND MINES.

“

Almost every product can be improved, �forcing companies to decide whether to �fund the efforts.

The problem

The devotion to perfection can energize—�or bankrupt—firms.

why it matters

Take some risks and evaluate designers �based on customer-success metrics.

The solution

Workforce 2025:

Power Shifts

Attracting Top

Talent: A Workplace Flexibility Checklist

The COVID-19 Pandemic

Hubris is a business liability.

In 2005 and 2006, there were alarm

bells about a potential financial crisis,

but many leaders chose not to listen.

Their intransigence ultimately caused

a huge amount of harm to their stakeholders and their reputations.

The Great Financial Crisis

We’ve had dizzying times before, and they’ve provided lessons that modern leaders can use.

Lessons from Other Turbulent Times

Don’t neglect the balance sheet.

Many leaders were caught off guard �when interest rates skyrocketed, peaking �at 14 percent, and the debt loads of their organizations went from manageable to unsustainable. Leaders needed to keep �a better eye out for early signs of �troubling trends.

The Great Inflation Crisis

Temperament matters.

In a time of true crisis, employees want

to know that their leaders have their

backs. President Franklin D. Roosevelt inspired many in the United States

as he led with a combination of

intelligence, confidence, and optimism.

The Great Depression

2020–2022

2008–2009

1972–1974

1929–1939

Hover over years to�learn more

Leaders aren’t the only ones dazed and confused, of course. Indeed, based on many surveys, ordinary workers are far more wary of what AI, trade wars, and the other 2025 disruptions will do to their lives. It’s not hard to see why, when C-suite executives estimate that nearly 60 percent of entry-level roles will be eliminated by AI, according to one survey from upskilling-software provider edX. The onus is on leaders for getting workers to buy into changes such as new work assignments, additional training, or just doing more with less.

One of the biggest mistakes leaders make is trying to shield their teams from disruption instead of guiding them through it. It’s a natural response, particularly in the corporate world. But HR and communications experts say leaders do better if they communicate early, set clear expectations, and do not change course without explanation. That can help employee sentiment hold steady—even in volatile environments. “People can handle disruption when they have something solid to hold on to,” says Eric McNulty, associate director of the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative at Harvard University.

That buy-in is critical, because organizations are increasingly finding that they can’t just foist something on employees and expect success. Perhaps the biggest evidence for this relates to employee training, something that is becoming critical as firms seek to upskill workers trying to engage with AI. In all, firms spend nearly $100 billion a year on corporate-training programs, but most employees feel it is more of a check-the-box exercise. Indeed, one study found that less than a quarter of employees say they are using their company’s AI-skills training programs. It’s not for lack of interest; almost two in five said they would leave their job for a place with better AI training.

Some leaders are taking a collaborative approach when it comes to big challenges, hoping that keeping teams abreast of what’s going on will give them more of a chance to positively impact the company’s situation before things turn dire. Lawford, the NuVista CEO, used to have department leaders give status reports individually to senior executives. Now, he says, they all meet at the same time, which gives everyone a better sense of where the company is going and how best to craft solutions together. “We, as the executive team, don’t want to show up to say, ‘By the way, this is how we are reacting,’” he says.

“

These help a

company’s ability

to take a punch.

Managing People

Once an afterthought for most CEOs, supply chains became a top priority during the pandemic—and that was before the word tariff was so commonly used. Between the pandemic and now, many organizations began massive supply-chain overhauls. Some of their changes were done to lessen the reliance on one country supplying critical parts or products. Other firms spent millions on digital transformation, hoping the ability to more precisely analyze inventory, production, and demand data would allow their factories and logistics operations to become far more productive. And firms worldwide spent an estimated $11 billion to add robots to warehouses and factories, hoping automation could speed up production times and cut overall costs.

Then came the April tariff surprise from the US, which upended many of those commitments. And that upending has continued as more large tariffs keep coming—seemingly on a weekly basis. That of course has thrown a wrench in the plans of nearly any company that produces goods in one country and sells them in another. Most companies set up their supply chains assuming it would be relatively inexpensive to move parts, products, and people around the world, says John Jullens, founder of Arbalète, a supply-chain consultancy. “Companies have to be rethinking that because we’re moving away from that relatively frictionless world,” he says.

A tariff-inspired cost crunch could force a CEO’s hand and put a halt to any long-term supply-chain plans. “Everyone has a fiduciary responsibility,” says Erik Olson, a Korn Ferry senior client partner. However, experts caution that CEOs shouldn’t just cancel whatever long-term supply-chain remodeling their firms were undertaking before the trade war started. Companies can’t just stop in the middle of a digital transformation, for instance. Without fully following through on implementing AI or robotics, a company could wind up spending money and not seeing any gains.

Most experts say there are no easy answers here, but that in general, CEOs should be looking to build more toughness and adaptability into their supply chains. In the short term, companies can build up inventories in case of shortages or build better relationships with their suppliers, helping them with financing, for example. “These help a company’s ability to take a punch,” Jullens says. At the same time, companies can build resiliency by broadening their supplier base and testing alternative ways to build products. Finally, the long-term goal should be to help supply-chain executives make faster decisions when it comes to product design, logistics, and production.

These are big organizational changes, Jullens says, and all this will take human brainpower. CEOs should be looking for executives who are not only on top of how current events are impacting the company’s operations, but also able to design and present a compelling future supply chain. After the US announced its first major round of global tariffs, an aerospace CEO confided to Olson that she was livid that her supply-chain executives didn’t have an incisive next step. “She wanted to immediately ask for new talent,” Olson says.

“

It all hit the world

all at the same time and everyone was saying it’s all bad.

Supply Chains

Million terabytes

328.77

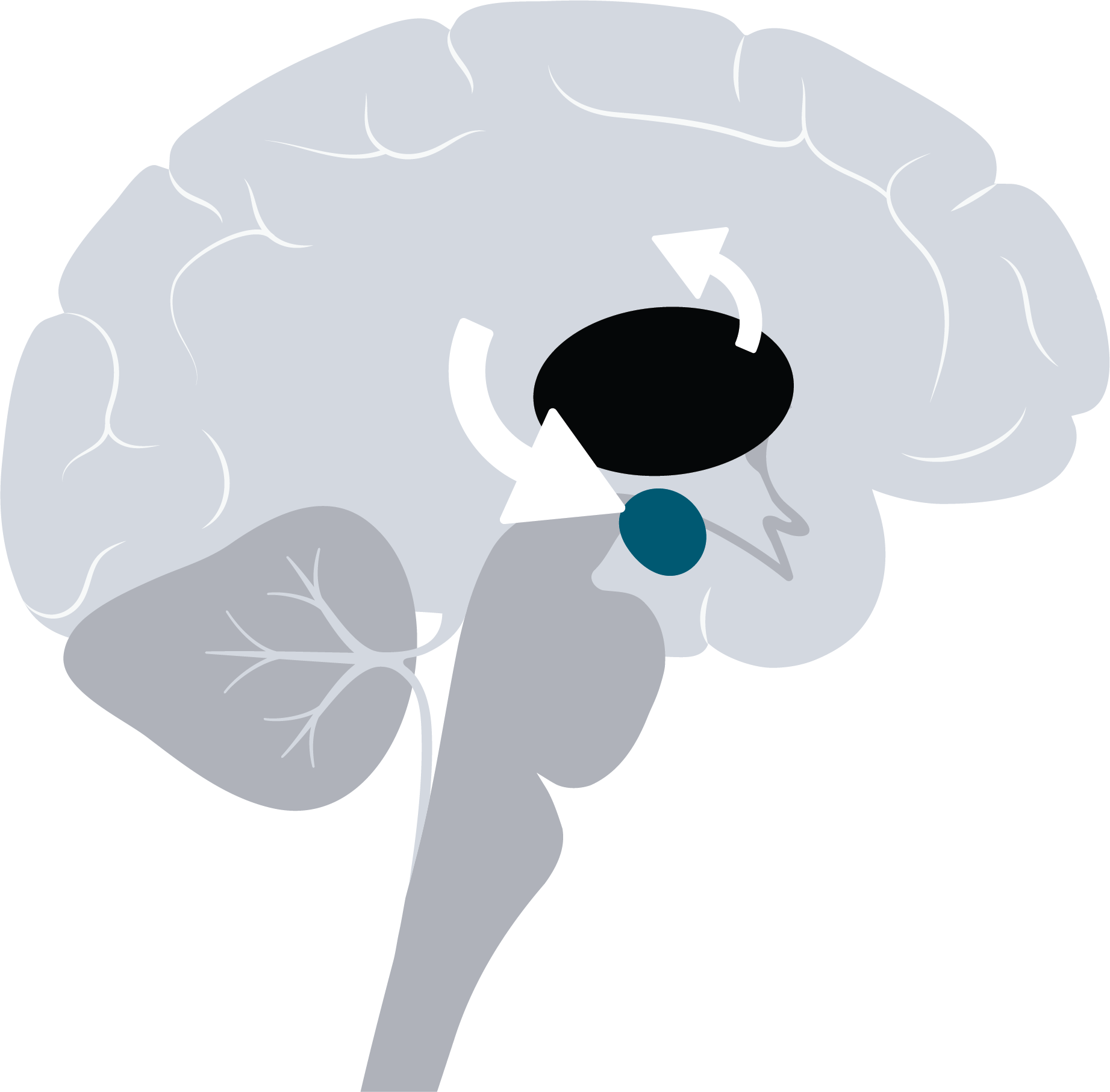

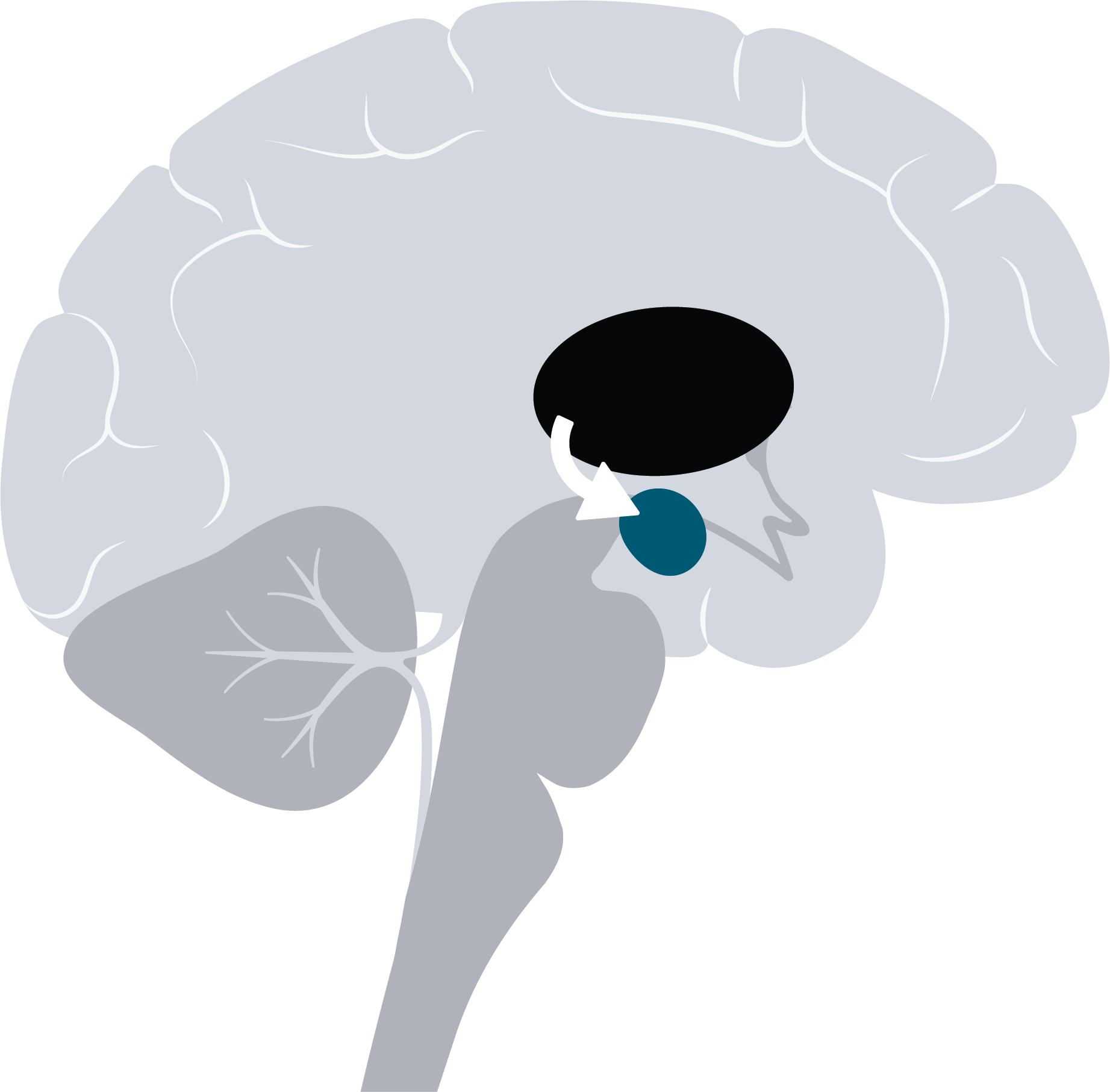

Leaders immersed in crises may not realize it, but being bombarded by information actually makes one part of the brain work against the other. Uncertainty, fear, and anxiety can trigger the amygdala, the part of the brain that governs �a human’s flight-or-fight instinct. If the amygdala’s response is powerful, it can send an immediate reaction to the brain’s central relay station, the thalamus, overwhelming any information from the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that handles critical thinking and complex decision-making.

Battles in the Brain

Amount of information created�each day, equivalent to more than 164 trillion copies of War and Peace.

Words

Number of words Americans�process each day, which is like�reading two books daily.

100,000

Gigabytes

Amount of information an�average person consumes each�day, equivalent to 16 movies.

74

Cortex

Cortex

Thalamus

Amygdala

Thalamus

Amygdala

Normal circumstances

Amygdala hijack

Keep your head down. Just ignore the topic. That’s been the conventional wisdom for leaders when it comes to politics. It’s certainly something many leaders prefer. More than half—52 percent—of company executives said their CEOs would be less vocal in 2025 than previous years, according to a survey from software provider Benevity. But what happens when politics becomes the most talked-about issue? Worse, what do bosses do when customers say they’ll take their business elsewhere based on the firm’s relationships with the federal government, or if employees believe a firm’s return-to-office policies are being determined by the boss’s political leanings?

That’s the situation many bosses find themselves in. With a client, the wrong step can be particularly costly. “You risk your reputation, you risk the business, and it can blow back on the organization,” says Louis Montgomery Jr., a principal at Korn Ferry’s HR Center of Expertise. Even when the boss doesn’t say a word, that doesn’t stop employees from thinking the boss cares about politics. Indeed, according to a 2024 survey from career-software company ResumeHelp, 59 percent of employees believe their manager’s political beliefs influence their management style.

Experts say the best answer is to be very nuanced around discussing politics, separating it into two situations: times when leaders should talk and times when they should gently steer away from the topic. Some light political discussion is OK, too; for example, in sectors directly impacted by immediate political moves, such as government and defense contracting. Indeed, some companies did use lobbying and other political discussions to get carve-outs from the US during the early days of the trade war. If a firm or sector is falling in or out of favor, political nuances will naturally emerge on a regular basis. “It’s discussion of administration policies as they affect future business,” says Montgomery, who navigates these conversations by sticking to the business topics at hand.

Then there are the thornier situations, when clients, employees, or other stakeholders bring up the topic. Almost a quarter of workers say they have witnessed a colleague behave aggressively or counterproductively because of their political beliefs. Leaders might feel stuck when someone else talks politics. Here, experts advise deftly pivoting. “Steer them directly back to what’s important to them and their organization,” says organizational strategist Kim Waller, a senior client partner at Korn Ferry. “Otherwise, it’s land mines.”

“

THE GENERAL ENERGY AND HOPEFULNESS AMONG LEADERS

iS LOW AND DEPRESSiVE

FEELiNGS ARE SO HiGH.

Political Issues

World’s Most Admired Companies 2025: Rebels with a Plan

VIEW THE

PODCAST

READ THE

FULL MAGAZINE

TEMPERAMENT

VIEW THE

PODCAST

READ THE

FULL MAGAZINE

By Russell Pearlman / Illustrations by Tim Ames

This spring, during a routine check-in with his manufacturing CEO client, the vendor noticed that the boss was distracted. The leader’s strategy had been upended by the new US tariff policies, impacting both the company’s day-to-day business and also a longer-term reorganization. Plus, he was getting pushback from investors over the firm’s quickly sinking stock price. The normally affable, open CEO was curt, irritable, even rude. “I felt really badly for him,” says the vendor, who asked not to be named to preserve his business relationship.�

Right now, CEO temperament is the topic of conversation in client calls, team meetings, and professional gatherings. Leadership coach Saara Haapanen was at a conference in April where the topic was ostensibly how HR departments could shape corporate culture, but the issue of how bosses are leading right now kept coming up. Managers, particularly senior-level ones, she says, are struggling because �they feel like they’re under assault. “Not everything is an emergency,” she says, “but when you’re being inundated it can be tough to figure what really is dangerous.” Indeed, Kevin Cashman, Korn Ferry’s vice chairman of CEO and enterprise leadership, agrees. “The general energy and hopefulness among leaders is low, and depressive feelings are so high,” he says.

When everything seems uncertain, it can be tempting for leaders to default to a more traditional so-called “directive,” or authoritative, approach to management. Do this. Do that. No dissent. It is a style that experts say can be valuable in the short term if everything is really on the brink. But today, many of the same experts say some perspective is in order. Even though it seems like everything is apocalyptic for the firm, it’s most likely not the case. Instead, most of today’s mounting disruptions boil down to difficult but manageable challenges around growth, expenses, technology, and people. Top bosses likely will find a combination of leadership styles—the ability to articulate a shared mission or the knack to generate consensus, for example—that will be more effective than just relying on the directive approach. “People don’t need more control; they need more clarity, care, and coaching,” Haapanen says.�

If leaders are finding themselves angry, afraid, or irritable, it can be valuable to turn to other leaders in their firm who may be feeling the same way. Pausing and identifying the emotion can help mitigate its impact and reduce stress, Haapanen says. “When a leader is grounded it helps the whole team feel steady,” she says. Most importantly, experts say, leaders should fall back on their sense of purpose and the purpose of the organization. By reminding teams, and themselves, why the work matters, leaders can not only reduce the fears of the uncertain environment, but also increase the motivation of employees.

“

STEER THEM DIRECTLY

BACK TO WHAT’S

IMPORTANT TO THEM

AND THEIR ORGANIZATION—

OTHERWISE, IT’S

LAND MINES.

Be ready to pivot.

Conditions turned quickly, but the best firms—and leaders—adapted to the circumstances. It wasn’t just getting people to work remotely, either. Leaders embraced new ways to manage, innovate, and inspire.

World’s Most Admired Companies 2025: Rebels with a Plan