Three Grand Slam titles. The first Black man selected to the U.S. Davis Cup team. Presidential Medal of Freedom and Emmy Award winner.

Richmond native. Arthur Ashe was all of those and much more.

We look back at the remarkable path of a legend on and off the court.

A RICHMOND LEGEND

AP Photo/Brian Horton

Ashe is 6 when his mother, Mattie, dies of complications from surgery at age 28. His father, Arthur Sr., is a caretaker of Richmond city playgrounds, and Arthur Jr., learns tennis from coaches/mentors such as Virginia Union student Ronald Charity and Lynchburg physician Robert Walter Johnson, even as racism limited where he could compete.

LEGACY ON AND OFF THE COURT

Remembering ARTHUR ASHE, civil rights activist,

Grand Slam champ and Virginia native

By David Teel - Richmond Times-Dispatch

EARLY CHALLENGES

“When I decided to leave Richmond. I left all that Richmond stood for at the time — its segregation, its conservatism, its parochial thinking, its slow progress toward equality, its lack of opportunity for talented Black people.”

— Arthur Ashe in 1981

After three years at all-Black Maggie Walker High, Ashe, for tennis purposes, relocates to St. Louis for his senior year of high school. He attends University of California, Los Angeles, where he studies business administration and leads the Bruins to the 1965 national championship.

But the sport and his social activism make him a globetrotter. Ashe wins tournaments in South Africa, Sweden, Canada, Germany, Italy, France, Australia, the Netherlands and Spain. He protests apartheid in South Africa and his native country’s treatment of Haitian refugees.

“I always think, looking back, that Arthur was kind of the forerunner to Barack Obama.”

— Donald Dell, Ashe’s agent and attorney

CITIZEN OF THE WORLD

In 1968, amid nationwide racial tensions, Ashe becomes the first Black man to win a Grand Slam singles title, capturing the U.S. Open with a grueling, five-set victory over Dutchman Tom Okker, 14-12, 5-7, 6-3, 3-6, 6-3. Ashe’s younger brother, Johnnie, helps make it happen. A Marine serving in Vietnam in 1967, Johnnie volunteers for a second tour of duty there to spare Arthur, an Army officer stationed at West Point, New York, a combat assignment. The military’s unwritten policy was that siblings not serve in combat simultaneously. Arthur does not learn of Johnnie’s gesture until much later in life.

“If I’d have talked to Arthur about it, he’d have tried to talk me out of it. I tell people without any hesitation it was a God thought.”

— Johnnie Ashe

BROTHERLY LOVE

Activism does not come naturally to Ashe, even as his public acclaim grows. Indeed, he is scolded by some for not being more assertive on matters of social justice, criticism he takes to heart. When his visa application to compete in South Africa is denied three times, Ashe plays a role in that nation being banned from the Davis Cup. Once allowed into South Africa in 1973, Ashe is greeted as a hero by Blacks, but the apartheid he witnesses reminds him of his youth and moved him to further advocacy. Years later, The New York Times’ William C. Rhoden compares Ashe to baseball’s Jackie Robinson as a sports and social pioneer.

“I guess I appreciate the fact some people take my views seriously,” Ashe tells The Times-Dispatch's Bob Lipper in 1989. “I’m in a stage of my life in which I have confidence in my opinions. I have the experience and the courage and the background to say some things about some subjects I feel I have expertise in.”

FINDING HIS VOICE

The bigotry of his youth notwithstanding, Ashe and Richmond never abandon one another. Ashe returns to the city for amateur and professional events, winning 1968 Davis Cup matches at Byrd Park, a venue closed to Black people during his childhood, and a tournament at Richmond Coliseum in 1976. In the ensuing years, VCU awards him an honorary doctorate, the city unveils an Ashe statue on Monument Avenue, and the Boulevard is renamed Arthur Ashe Boulevard.

The late Bill Millsaps, venerable sports columnist for The Times-Dispatch, calls Ashe the most interesting athlete he ever chronicled. “Arthur’s passions not only generated heat,” Millsaps writes. “They also produced light. He was a thoughtful, curious, empathetic, good-humored man of strong convictions. An intellectual, even.”

RECONCILIATION

WATCH: Arthur Ashe Boulevard unveiled

With two Grand Slam singles titles — the 1968 U.S. Open and 1970 Australian Open — on his resume, Ashe’s Hall of Fame credentials are apparent long before Wimbledon in 1975. But his upset there of Jimmy Connors in the gentlemen’s singles final is his signature tennis moment.

“The match was supposed to be a slaughter,” Ashe wrote in one of his nine books, “and I was to be the sacrificial lamb.”

'SACRIFICIAL LAMB’

Like Ashe, Connors had played collegiately at UCLA, but otherwise, the two were polar opposites and tense rivals. Ashe is 31, understated and reflective, Connors 22, brash and blunt. Moreover, tennis politics pits them against one another in legal entanglements. Atop the world rankings, Connors is heavily favored, but Ashe prevails 6-1, 6-1, 5-7, 6-4 for his third and final Grand Slam singles championship, at a venue he and others had boycotted two years earlier over the suspension of a Yugoslavian player who had declined to play Davis Cup.

Ashe’s health begins to deteriorate in 1979, when, at age 36, he suffers a heart attack and undergoes bypass surgery. Less than a year later, Ashe announces his retirement from tennis. His final competitive match is a 6-7, 6-2, 6-4 setback to Christophe Freyss in Kitzbuhel, Austria.

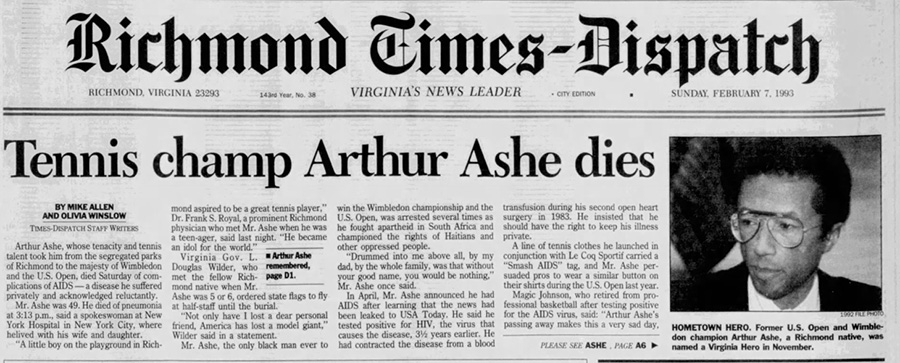

Alas, Ashe can not clear the hurdle of AIDs. He contracts the AIDs virus, HIV, likely from a blood transfusion during another heart surgery, and reveals his condition in 1992. He dies in New York City on Feb. 6, 1993, two months after speaking at the United Nations on World AIDS Day. He is 49 and buried at Woodland Cemetery in Richmond near his mother.

“I still have some health problems, some major problems,” Ashe tells The Times-Dispatch in 1989. “But I live with it. Like racism in Richmond, like heart attacks, like the wind and the sun — hey, as best you can, you try to make the most of these obstacles. They’re almost hurdles for you, and each hurdle you get over makes you stronger.”

HEALTH DECLINE

LISTEN: 1993 reception for the National Sports Awards

Like his life, Ashe's legacy and accolades transcend tennis.

He’s been enshrined in the International Tennis Hall of Fame and Virginia Sports Hall of Fame. The hub of the United States Tennis Association's venue for the U.S. Open in New York is Arthur Ashe Stadium.

The Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health, which Ashe founded in 1992, remains vibrant, and each year at its ESPY Awards, ESPN presents the Arthur Ashe Courage Award. Recipients include Muhammad Ali, Bill Russell, Pat Summitt, Pat Tillman and, most fitting, Nelson Mandela.

LEGACY AND AWARDS

Ashe won an Emmy Award in 1986 for co-writing a documentary based on his three-volume “A Hard to Glory: A History of the African-American Athlete,” and in 1993, President Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously. The United States Postal Service issued a stamp bearing Ashe's likeness in 2005, and UCLA created the Arthur Ashe Legacy Fund and Arthur Ashe Health and Wellness Center.

Arthur Robert Ashe

Jr. is born in segregated Richmond on July 10, 1943 at

St. Philip hospital.

VCU Libraries Gallery

1961

Times Dispatch file photo

Arthur Ashe Jr.

1968

U.S. Open championship

AP Photo/Marty Lederhandler

1976

At Westwood Racquet Club in Richmond

Don Rypka photo

Brother, Johnnie

Dad, Arthur, Sr.

Arthur Ashe, Jr.

1985: A handcuffed Arthur Ashe is led away from the South African Embassy by police in Washington, D.C. The retired tennis champion and 46 others were arrested near the embassy during their demonstration against apartheid policies of the South African government.

AP Photo/Lana Harris

Mixed doubles partners Jane Albert and Arthur Ashe beat Mexico's team to capture a gold medal for the United States.

AP Photo

The Arthur Ashe Monument, a bronze sculpture by Paul DiPasquale, stands on Monument Avenue in Richmond.

Mark Gormus/Times-Dispatch

1967: A statue Arthur Ashe, Jr. was presented to Maggie Walker High School, Ashe's alma mater.

Times-Dispatch file photo

AP file photo

AP file photo

1975

Wimbledon

AP Photo/Marty Lederhandler

1992

AIDS announcement

AP Photo/Manu Fernandez

Arthur Ashe Stadium

2023 ESPY Awards: U.S. Women's national soccer team accept the Arthur Ashe award for courage.

AP Photo/Mark J. Terrill

LISTEN: 2018 U.S. Open Arthur Ashe Kids Day

Pan American Games

Canada

1967

Arthur Ashe defeated Richard Crealy (Australia) in three sets to cop the Australian National Men's Singles Championship.

Australian Open

Australia

1970

AP Photo

Arthur Ashe holds the cup he won in the $50,000 World Championship Winter Finals in Rome.

World Championship Winter Finals

Italy

1972

AP Photo/Gianni Foggia

Arthur Ashe beat Tom Okker, (Netherlands) 6-2, 6-2 in the men's singles finals. Ashe picked up $12,000 in prize money and Okker cashed $6,000.

Stockholm Open Tennis Tournament

Sweden

1974

AP Photo/Reportagebild

Arthur Ashe defeated Björn Borg (Sweden) 6–4, 7–6 in men's singles finals.

Munich World Cup Tennis Tournament

Germany

1975

AP Photo

Arthur Ashe demonstrated against the Bush administration's policy on Haiti. He was later arrested during the protest.

Protest in support of Haitian refugees

Washington D.C.

1992

AP Photo

Arthur Ashe talks with Chairman Charles C. Diggs, D-Michigan, of the House Foreign Affairs subcommittee on Africa. In 1973 Ashe was granted an entry visa to compete in the South African Open.

Ashe denied a visa by South Africa

Washington D.C.

1970

AP Photo/Bob Daugherty