A sea of orange trees spread north from the downtown commercial district, thinning as gray foothills climbed into the schist canyons and woody arroyos of the San Gabriel Mountains. Welcome to 1970 in Upland, California, my home town. A quaint little bedroom community lush for its citrus groves and mountain panoramas. Cozy enough, but too familiar to contain my wildness.

I’d often peer out through the busted windows of my homeroom in Upland High, daydreaming about all the mountains I would someday climb, mysterious summits obscured by clouds and ten times the size of 10,064-foot Mt. Baldy (which I’d rampaged around for years), gleaming in the distance. But I couldn’t go it alone. I needed partners and a way to get to those mountains. So I organized a high school rock climbing club for the sole purpose of enlisting a partner with a car.

The club got shut down after our first overnight field trip to Joshua Tree National Monument, when a chaperon caught several students with a fifth of Pappy Van Winkle and a foreign exchange student from Haifa was found wandering the desert in her panties. No matter, since by then I’d partnered with Eric “Ricky” Accomazzo and schooled him on the little I knew about ropework. And we’d be climbing plenty since Ricky had a car—a powder-blue Ford Pinto we drove into the junkyard over the following years, during which Ricky distinguished himself as king of the shit-your-pants runout.

Ricky—an all-everything water polo player, with a manner just as smooth as Mezzaluna—was to climbing what Sinatra was to song. From Yosemite granite to Chamonix ice, Ricky climbed the hardest new routes with a casual artistry that led our Yosemite brother Dale Bard to once ask, “What’s that guy made of?”

“He’s Italian,” I said, which didn’t explain Ricky hiking a glassy, Royal Arches slab that Dale and I had just backed off and declared un-leadable. Back in high school, Ricky and I were just two kids thrilled to get our feet off the ground. Then we were three.

Text:

John Long

One Dark and Stormy September Night

Richard, Ricky, and I were soon scratching over the boulders at Mount Rubidoux, a scruffy practice climbing area near Riverside, California. We pooled our money and bought a nylon climbing rope and a skeleton rack, and over the 1970 school year and through the summer, if we weren’t climbing, we were reading, thinking, or talking about climbing. We’d memorized quotes and immortal passages, including the mawkish book jacket copy from Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage, Starlight and Storm, even The Ascent of Rum Doodle. We’d recite the grave stuff sotto voce and then yell the gallant summit pronouncements at the top of our lungs, with faux French and German accents we learned from listening to Inspector Clouseau and watching Hogan’s Heroes. Most of this went down in Richard’s cinderblock basement bungalow, later known simply as “The Basement.”

Richard lived up in the foothills, above the citrus groves just shy of the mountains. His nearest neighbor was half a mile away. A dirt drive found his split-level lodging (kitchen and bedroom above, basement below), set back from a twisty two-lane road flanking a rocky streambed that occasionally overflowed during winter rains. You needed a compass to ever find the place, and on my first visit, Richard’s cranky old German Shepherd bit my leg. Richard’s mom, two siblings, grandparents, and twenty-odd critters, lived in Old MacDonald’s other farm, several hundred yards downhill from The Basement.

An artist friend of Richard’s had painted an exposed joist with a stylized cordillera of mountains, starting with K2 by the left wall and ending with the Matterhorn by the door on the right. In the presence of these giants, we dreamed away many evenings, recounting dazzling alpine epics, listening to Jimi Hendrix and Pink Floyd on Richard’s squeaky old tape deck, and bonging rag weed he grew in the arid gulch behind The Basement. No one ever bothered us. When you’re eighteen, that kind of privacy and the cloistered vibe of The Basement made us feel like sovereigns of a magic castle. And all the while, Richard held court with a corncob pipe.

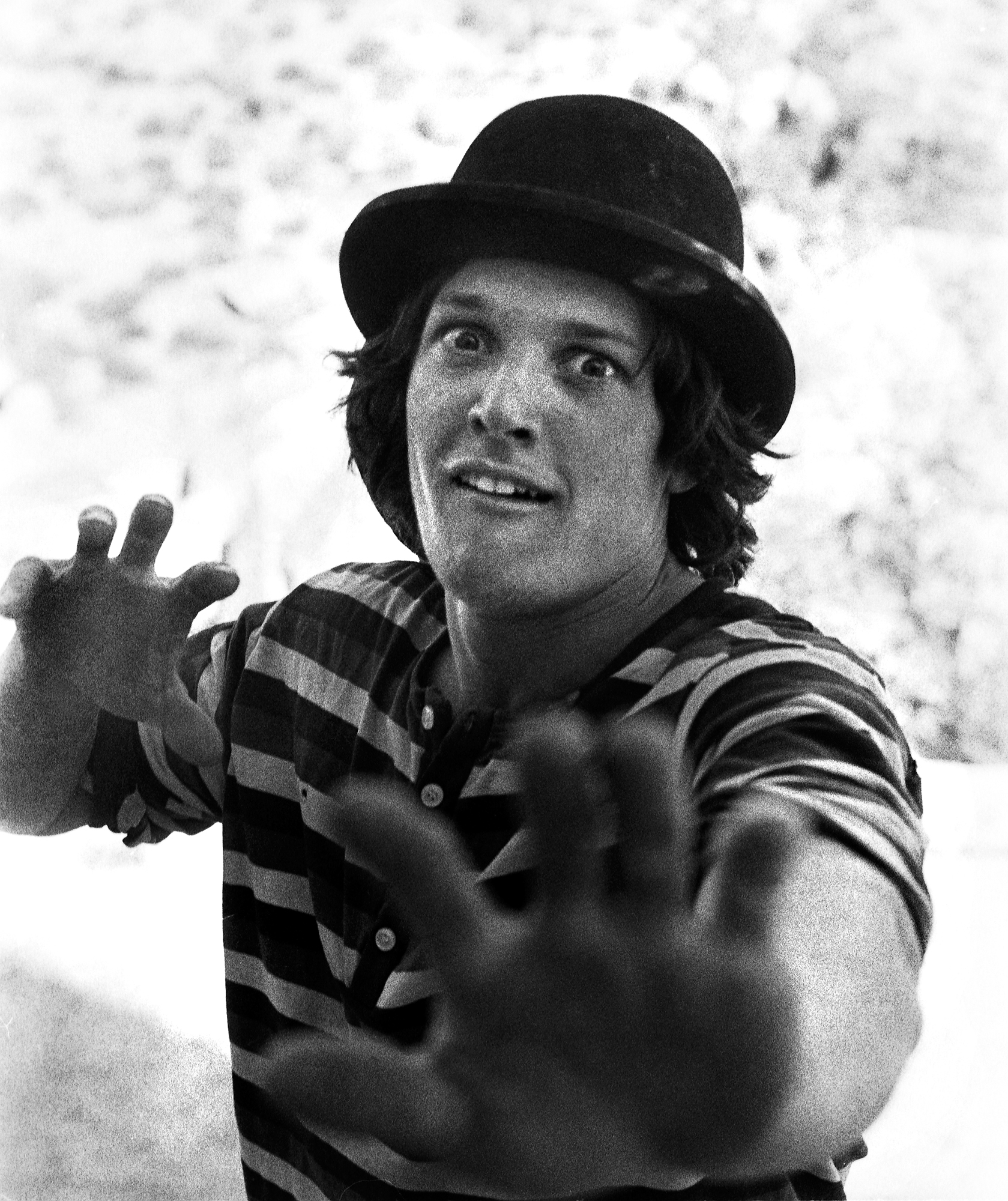

John Long

Eric "Ricky" Accomazzo

No one remembers who coined it, only that “Stonemaster” materialized in our conversation. Just mentioning the name conjured The Stonemaster himself, and his lightning struck us right between the eyes. We jumped up and started yelling over each other. Rash, reckless plans were voiced at lightspeed, and I half-expected pentagrams to appear on the rafters and horse heads to start bobbing round The Basement. Nobody cared. Bugger Herzog and Messner, and never mind the Himalayas. This was about us, and stupendous rocks, since we were rock climbers, after all. There was El Capitan and Middle Cathedral and hundreds of gallant, historical climbs at nearby Tahquitz and Suicide rocks, and we’d climb them all in a minute. All of this spewed forth the moment we realized that the only thing holding us back was the pissant size of our dreams. It felt like getting birthed out the barrel of a cannon.

Only later would I realize that the shift from reciting other people’s triumphs to striving for your own always involves battling fear of the unknown, with all that uncertainty. Fear of failure. Fear of dying horribly. Fear of fear. There’s always more fear. After months upon months, books upon books, our dream at last dashed against the unknown like a fly against a windowpane. Then The Stonemaster threw open the window.

An Unexpected Guest

down by Sentinel Bridge.

Somewhere in between, I fell down, dreaming.

Last night I picked a shooting star,

This morning, I swept petals from my tent.

As we kept marching around The Basement and babbling about the fantastic adventures sure to follow, The Stonemaster was ushering us onto the High Lonesome, where the Buhls and Terrays once roamed—and where scores of them had died. I had nothing to scale this off, no metaphor, since our quest didn’t feel like anything we’d ever experienced. Either way, we were already two rope lengths up, and had been for a while. There was no bailing now. The only thing we had was each other and a pole star we could feel but not yet see or imagine.

Around midnight, I got on my bike for the six-mile pedal back to my tiny dorm room at the University of La Verne, where I was slogging through my freshman year. From Richard’s house, a lung-busting climb found the steep and twisting road rifling down from Mt. Baldy. I could coast for a couple of miles, at what felt like Mach 1, rarely encountering cars while tracking the single white lane line that, in the dead of night, sans headlamp, was my only hope of not flying off the road. But that night, a stiff headwind held me nearly in place and I floated down the road in a trance, touched by the fragrance of orange blossoms. My life, which was all and only mine, had just begun.

Over the following months, The Stonemaster tornadoed around us, tapping his toes and scratching his balls. Grousing when we dithered at a danger. Tormenting us with the same question: Who are you, really? It sounds prosaic now, but not to teenaged misfits with no charts and little experience. We could only answer through an odyssey, so we’d need a proper crew. Fortune planted the question in the ears of Mike Graham, Robs Muir, and a handful of other young climbers scattered over Southern California, and all of us were soon on board. From the moment we first cast off, The Stonemaster shot us into action with a velocity that broke one of our backs, busted another nearly in half, killed several outright, and had the other half dozen of us pawing at sloping holds.

Suicide Rock, in Idyllwild, California, served as our training ground and cultural laboratory. East of Suicide, a mile across Strawberry Valley, rose massive Tahquitz Rock, crucible of American climbing mores and incubator of the Yosemite pioneers. Tahquitz always felt hallowed and elderly—like a famous old uncle you were proud of but never visited much because he was, well, old. Suicide felt brand-spanking-new because most of the routes had gone up in the previous half-dozen years—courtesy of Pat Callis, Charlie Raymond, and Bud Couch—and there were plenty more new ones for the taking. The rock tended toward sweeping (up to about 300 feet), high-angled slabs, faces, and arêtes, with extravagant runouts on polished granite. In an era long before sticky rubber, casting off on a Suicide test piece had the feel and jeopardy of big game hunting with your bare hands. And one of the best of the early hunters was Mike Graham, known in later years as Gramicci.

Mike had the long, lean frame of an Olympic swimmer and the insouciant dash of a surfer, which he was, having grown up in Newport Beach. With the gift of a natural and the drive of a beatnik, not once, in all the years I knew and climbed with Mike, did he ever round into top shape. He never needed to. He did everything on native skill and guts. If you were to ask Jim Bridwell to name the greatest, go-for-broke lead he’d ever seen, it was Gramicci cranking an eighty-foot, unprotected layback during the yet-unrepeated first ascent of Gold Ribbon, on Ribbon Falls, Yosemite.

Mike worked at Ski Mart, a big outdoor recreation retailer, and kept us all in the finest gear (later, Robs Muir, Ricky Accomazzo, and I would work at Ski Mart as well). Mike also fashioned the first Stonemaster logo, with the sizzling lightning bolt, forever chalked beneath the one of the world’s most famous boulder problem, Midnight Lightning. It was through Mike that we met Gib Lewis and Bill Antel.

Gib had a bottle-brush blond afro and a learning curve that never flattened out. An adventure sports generalist who later mastered windsurfing and laid down the grimmest ski descents on record, Gib started out strong and just kept getting better and better. Bill apparently stepped from the shadows straight onto world-class face climbs. I never knew where Bill came from and didn’t care because the Stonemasters were like the French Foreign Legion in that regard—your past was forgotten the moment you signed on.

Early Journeys

“You’re not going to believe this one, Johnny,” Ricky said one day after school. That morning, on a restless hunch, Ricky drove up into the foothills and started snooping around a mangy canyon for a misplaced Shiprock or Half Dome. Instead, he stumbled across a long-haired maniac running laps on a thirty-foot mud cliff.

“Another climber?” I said. “In Upland?”

“Name’s Richard,” said Ricky. “Richard Harrison. Says he dropped outta high school because it was cutting into his climbing time.” What were the odds? Nobody quit high school to go climbing back then. Not in the U.S. anyway.

Richard grew up in an artist’s culture (his father was a renowned woodworker) and he developed a shine for alternative lifestyles that seemed so daring that the rest of us wondered how anyone could pull it off and stay out of jail. Each Stonemaster (as we later styled ourselves) brought to the group ingredients that were blended into our collective gestalt. Richard brought the main course: following your own prerogative. If that squared with others—fine. If not, “Tastes differ,” he’d often say, with the coolest affect you’ve ever seen. Richard went on to climb more routes in more places than most of us combined, always so much on the down-low he might have remained anonymous but for his full-page photo in Meyers’ seminal Yosemite Climber, cranking an early ascent of Nabisco Wall with a young John Yablonski belaying. It’s curious to consider how that picture and the thousand-and-one adventures that followed all sprang from one dark and stormy September night in 1972.

The night started out like so many others: strains of Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly mingling with clouds of weed smoke and tangy incense so thick I could scarcely see the summit of Broad Peak on the joist, six feet away. Wind lashed The Basement and thunder rumbled down from the San Gabriels. For months we’d languished - reading, talking, dreaming. Gazing toward a future we wanted with all our might, where our lives would surely catch fire. The waiting was killing us, so I once again started in on Buhl’s forced bivouac on Nanga Parbat. The heat was gone. I shifted to Messner’s solo of Les Droites. The words were cold and lifeless. We sat there, in the poverty of posers, with no catalyst for our scattered energies. Who were we with no true north? No spark? So ran our first experience with unclaimed moments, where big bangs sometimes emerge. You never see them coming.

What’s more (and decades before Joe Public realized the significance), rock climbing’s provenance, always written by white males, was expansively amended by Carolyn “Lynn” Hill (future World Sport Climbing Champion), Mari Gingery (whose mother was born in Japan), and Mariah Cranor (who later ran Black Diamond Equipment), card-carrying Stonemasters, there from Day One. These three women climbed just as hard, sometimes harder, than us fellows, insuring that by the mid 1970s, the democratization of climbing outpaced all other sports by a wide margin.

So we had a name, a lightning bolt, and marching orders to peaks unknown, but as a group, we’d done little more than repeat Suicide’s standard hardman routes and shoot off our mouths. We needed some dramatic victory to assert our arrival and establish the clout of The Stonemaster. But nobody was quite sure how.

John Bachar

Tobin Sorenson

Robs Muir and Jim Hoagland were both UC Riverside students and standouts at Mt. Rubidoux and Suicide. It took the pair several tries, but they managed the first continuous ascent of Valhalla, one of America’s few 5.11s and a route that had a reputation the size of its creator, Bud Couch, a six-foot-four college professor who lived in Idyllwild and lorded over Suicide with flinty disdain.

Bud was the last, and possibly the best, of the traditional line of Idyllwild masters that ran back forty years to John Mendenhall, the father of California rock climbing. Bud had his circle of partners, whose names and photos were peppered throughout the guidebooks. We were awestruck by these guys and secretly wanted their blessing. Instead, they laughed as we tumbled all over their rock. I was too proud and insecure to roll with such ridicule, but far worse was getting dressed down by the board-certified leaders of various outing clubs that rounded out the Idyllwild climbing scene during those dog days. For ages, these clubs had floundered up the same gullies in humorless cavalcades; the very gullies we’d down-climb (unroped, of course) to return to our packs. A couple of times when we ran into a battalion of these people and the leader launched into another diatribe, barking and spitting in our faces, things nearly got ugly.

The whole shebang felt absurd. There you had a cult of illustrious has-beens mostly loafing in the shade, drinking malt liquor and tossing off snide comments, while a regular platoon, led by phobic drill sergeants, queued for their umpteenth slog up some dark and dreary ditch. One of Suicide’s most beautiful formations was called the Weeping Wall, and it was crying for good reason. For millions of years, this fantastic rock slab had drawn rain and wind upon itself to fashion resources that were largely going unused.

“Time to step it up,” Richard concluded one night in The Basement, “or we ain’t going nowhere.”

Shortly after Robs’ and Jim’s victory, we all shot for Valhalla, and we all got there. (Valhalla immediately became the prerequisite for becoming a Stonemaster, and Mike kept a journal that logged the first dozen or so ascents.) In another few months, we’d repeated every old test piece worth doing, yet the Stonemasters scarcely grew larger for our efforts, efforts that inspired no one but pissed off everybody, leaving them anxious and guarded. But while the duffers trudged up their gullies, and the old guard slowly faded to black, anyone new had a different dance to follow, and eventually, many did. The Stonemasters had arrived, the party was on, and everyone was invited.

Valhalla

was more valuable.

to gain something that

giving up something

The idea of

The season we all got liftoff saw the Stonemasters pull down dozens of new climbs and first free ascents at Suicide and Tahquitz, and out at Joshua Tree. New Generations, Iron Cross, Drain Pipe, Ten Carrot Gold, Green Arch, Ultimatum, Le Toit, The Flakes, Jumping Jack Crack, Ski Tracks, and countless others on today’s climbers' tick lists were all climbed in rapid succession. Most routes were dispatched mob-style because no one could bear missing out on the glory. Plus, it was always more laughs with a conga line five or ten strong, and far more dangerous because the Suicide climbs, in particular, were often protected by bolts, and only bolts, and a leader was obliged to run the rope halfway to Kingdom Come before breaking out the drill.

Here was the climbing equivalent of glass blowing: delicate and tricky. You were certain to get burned if the thing got away from you, and it could in a flash. This was before EBs, when the shoe of choice was either red PAs (Pierre Alan) or brown RDs (René Desmaison), which edged okay but had the friction coefficient of a shovel. The slightest misstep and you were off for the big one, and nobody took the big one as often or as dramatically as Tobin Sorenson.

Safety in Numbers

Most climbers know of Tobin Sorenson as the madman who, in blue jeans and a “Jesus Saves” sweatshirt, soloed the North Face of the Matterhorn; or who, with the late, great, British alpinist, Alex McIntyre, made the first alpine-style ascent of the Harlin Direct on the Eigerwand; or who joined Ricky Accomazzo on the germinal first ascent of the Dru Couloir Direct, in Chamonix—at that time the hardest ice climb in the Alps, and one of the first times a team bivouacked while suspended from ice screws. If you had to pick the world’s best overall climber from the 1970s, from alpine peaks to Yosemite’s big walls, few would argue if you gave the nod to Tobin. More than a friend and a partner, Tobin was a once in a lifetime experience. He answered The Stonemaster’s momentous question, Who are you, really? in ways we could never fully grasp.

Once-in-a-Lifetime Experience

Worship and veneration came naturally to Tobin, the oldest son of a Presbyterian minister. Though he would have considered it blasphemous to contrast any climber with the Almighty, Tobin would nevertheless risk your life and his own to secure his place alongside the Salathes and Pratts and Bridwells—all supreme artists in Tobin’s mind. Emily Dickinson said that art is a house that wants to be haunted. But Emily refers to how a house, inclined by history, naturally attracts the ghosts of the great ones who lived and tangled with similar challenges. Tobin seemed determined to inhabit the house with his own ghost. Why else would he follow hard cracks out at Joshua with a noose lashed round his neck, or race his sportscar on the wrong side of the road? And how was this germane to becoming a distinguished climber? All we knew for certain was that Tobin had some dreadful need to square off with his Maker every time out.

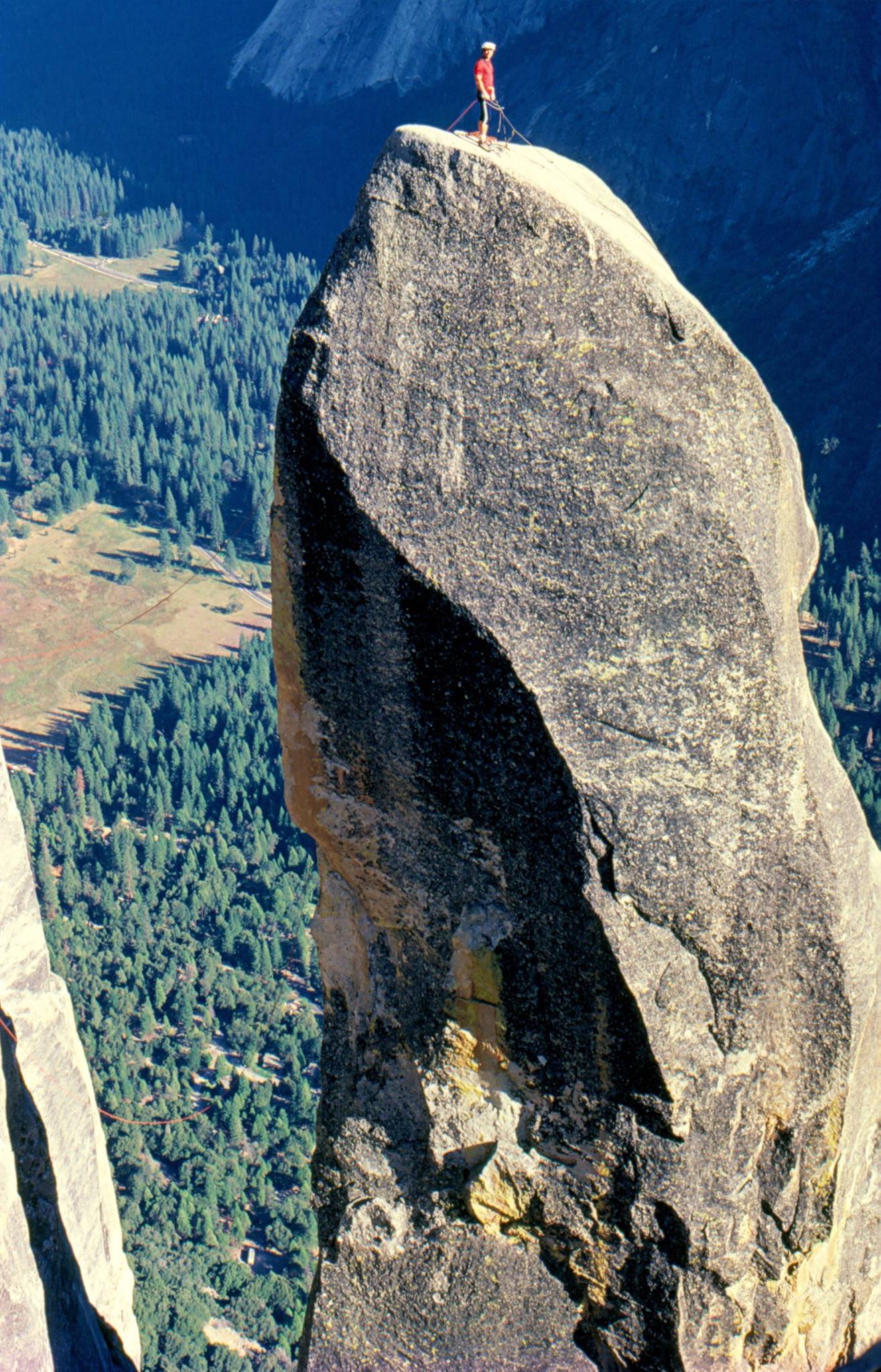

Though the rest of us could never match Tobin’s nerve and commitment, his example shifted the group’s paradigm from delinquent capers to a game of deadly seriousness—a shift accentuated by the newest Stonemaster, John Bachar, who through natural talent and obsessive dedication, transformed himself into one of the greatest figures in twentieth-century adventure sports. Though John always played his own tune—both on the rock and on the alto sax he used to torture us with—early on, he did so within the context of the group, and we all had the edgy rapture of watching John go where no climber had gone before. If ever a Stonemaster carried the name on his sleeve (and he scribbled it on his boots as well), it was John Bachar, Grand Templar of the entire movement.

John Yablonsky

Throughout 1973, the group energy arced up and found expression through several pivotal ascents. First came the Vampire, an old Royal Robbins aid route that took the boldest line up the baldest section of Tahquitz. Eight hundred feet long, with a flapjack-thin, expanding flake soaring up the glazed, southwest face, the Vampire was the closest thing we Southern Californians had to a big wall. When Ricky Accomazzo freed the A4 traverse on the third pitch, via an audacious, sideways leap to the expando flake (an improbable, though easier, traverse was later found a body length below), any notion we had about what a leader could and should do flew straight out the rain fly. With three 5.11 pitches in a row, the Vampire was, along with Yosemite’s Nabisco Wall, and Eldorado’s Naked Edge, one of America’s first multi-pitch, super free climbs.

The Vampire naturally led to Idyllwild’s most improbable free climbing prospect: Paisano Overhang, a twenty-five-foot, downturned roof crack that went free at 5.12c (the rating was not established for another decade, when Randy Leavitt and Tony Yaniro invented the climbing technique known as “Leavittation” to bag the second free ascent). The combination of grisly wide crack moves and A3 protection gave us a futuristic yardstick to measure any other crack on the face of the earth. If we could climb something as difficult and poorly protected (a fall would have likely been a backbreaker) as Paisano, what could stop us? And so, on the slipstream of these climbs, we made our summer pilgrimage to rock climbing’s grandest stage: Yosemite Valley. To that point, we’d made only brief sorties into the Valley, slowly developing our comfort level by picking off a couple of small walls and a celebrated crack or two. But in 1973, the moment the semester let out, we descended on Camp 4 en masse, determined to carve an existence out of Yosemite’s soaring expanse.

Double Trouble

The Big Valley

With Nuptse as our witness, soaring off the dusty joist, we recounted how, through sweat and fear, but the whole while laughing, we drew near The Stonemaster—not so much a being as an island in our souls. Through many epics did we find him, striving to become who we most revered, though not owing to our route-finding skills; rather, because The Stonemaster had sought us all along. By no other means could you find Wonderland, where the young and strong alight for a time and jump just as far as they can. Every old Stonemaster knows the place, still feels the wind on their faces. And in other haunts and in other ways, we might jump beyond ourselves. But only the young can live on those craggy shores, and we would land there no more.

Tobin Sorenson

Lynn Hill

In Tobin’s fierce nature, there was a touch of the feminine, as there is in every prince and pirate. But when he tied into a rope, he was all wildcat. During our early mob ascents, we never goaded Tobin, especially when he grabbed the lead. Rather, we gnashed our teeth and held our breath, because Tobin, though a great natural athlete, hadn’t technically caught up to the rest of us, but he charged as though his knickers (back then, he always wore knickers) were on fire. God must have adored him. It is the only explanation why Tobin survived the gigantic ragdoll falls he logged each and every weekend. His skill quickly approached his ambition and, praise the Lord, Tobin’s harrowing falls eventually declined. But so long as he lived, his goals outpaced his capacity—or anyone’s capacity. We were too young to appreciate where it all must lead, but from the day he first chalked up, Tobin Lee Sorenson was a dead man climbing. I believe the savage force that drove him and his magnificent sense of purpose derived, in large part, from his reverence of climbing history.

Within a few weeks of arriving in the Valley, the Stonemaster movement gained critical mass; out of necessity, we broke ranks with our small cadre of SoCal partners and teamed up with other kindred souls. Robs had already climbed the West Face of El Cap and we had some catching up to do. Richard and Kevin Worrall kickstarted the season with an early ascent of the Direct Route on Half Dome. Ricky, Gib, and future alpine hero Jay Smith climbed The Nose and I quickly followed suit, tying in with British ace Ron Fawcett. Directly on our heels climbed Richard and soulful English mountaineer Nick Estcourt (who, a few years later, perished in an avalanche, 6,500 meters up K2, during an early attempt on the West Ridge).

During those first months, the Stonemasters lived on the walls. But more pivotal than our first Grade VIs was the bond we forged with Jim Bridwell, the most practiced rock climber in the world and a carry-over from the Yosemite pioneers, most of whom fled The Ditch in the late 1960s.

If The Stonemaster himself had a right-hand man, it was Jim Bridwell, aka, “The Bird.” To recount another Bridwell story is to spin a broken record, but his influence cannot be overstated. Uncertainty, the Kryptonite of humanity, was Jim Bridwell’s daily bread. To climb with Jim, which we all did, was to embrace the boldest, newest, most outrageous adventure you could, each and every time out.

What followed were a thousand exploits that took Jim and me from El Cap in a day to Venezuela’s Angel Falls to the jungles of Borneo. Through Jim, we met Mark Chapman, Kevin Worral, Ron Kauk, Werner Braun, Billy Westbay, Ed Barry, Jim Orey, Rik Rieder, Dale Bard, and many others. During our first few seasons, we were all interchangeable partners.

But this was a many-sided posse. Nature had put a quietness in some, a ferocity in others, but all of us could best see daylight from high places. It was hard to get up high, where the margin for error is thin as a knifeblade and life is merely tolerated. More people had walked on the moon than had been on some of that granite. And all of us, when the wind picked up and the sun beat down and the rock turned into rubble, wished we’d never bothered. But we were touching life, discovering who we could be, and there’s magic in that. And so we loved the high places with devotion. And gratitude. We surrounded ourselves with people who made our hearts smile, worked ourselves into tight sports, and as Alice was promised, found Wonderland.

When the groups gusto grew too much for us Southern Californians to contain, our original group burst at the seams and The Stonemaster mojo splashed over one and all. By 1974 there were easily twenty-five Stonemasters (an ascent of Valhalla was no longer a criterion), and by 1975, most everyone in Camp Four was a charter member of the most unofficial club on the planet. Years later, French climber Laurent Dubois wrote that the Stonemasters “set a cultural standard aped by monkeys around the world.” The way it played out, the original movement diffused into the masses after a few short seasons. The touchstone was the counterculture animating the youth from many countries; but the cliffside transformed a mere ethos into a battle cry as close to something sacred as we’d ever experienced.

Our Yosemite saga was a subplot in which The Stonemaster himself played a leading role only in the beginning, when this existential experiment harmonized the needs of an entire generation of restless outcasts. It quickly assumed a life of its own, and The Stonemaster’s work was done. Knowing that the most valuable technique was the exit, none of us ever saw him go.

From the beginning, The Stonemaster provided a portal into the mysterious, a quest made ridiculous by climbing El Capitan thirty or forty times, something many climbers had now accomplished. After a dozen or so big walls, you could return to find challenge and, no doubt, danger, but you’d no longer encounter an unknown world. When we first jumped onto the Big Lonesome, our relationships, our clothes, even our language morphed to reflect the inner expedition. But over the years, the crazy clothes, lingo, and attitudes became ends in themselves, no longer predicated by jumping beyond our experience. We’d crisscrossed this particular ocean countless times, and in the process, a Stonemaster had come to mean little more than a formidable granite mariner—a rarity when we’d first attacked Suicide and Joshua Tree, but not anymore. Then Tobin died while trying to solo the North Face of Mt. Alberta (a feat later attempted by another Stonemaster, Mark Wilford). So boldly and so often had Tobin marched point for all Stonemasters, when every summit and every ending flowed into something new; but this time he’d led us into no-man’s land, where the future dead-ended with no exit and no retreat. We just hung our heads and stared at our shoes. Everything was fleeting. And when someone was gone, there was nothing left of them at all, forever, but it takes the rest of your life to ever accept it. If you ever do.

Especially early on, the Stonemasters moved freely between dreams and destruction. Because we were all forced to work on the rescue team (the only way to escape Yosemite’s seven-day camping limit), we’d handled our share of corpses. Our founding ranks had also been thinned when Bill Antel shattered his back on Rixon’s Pinnacle, and when Gib Lewis fell 100 feet to the deck—right in front of Ricky and me—while soloing the mottled ice falls in Lee Vining in the Eastern Sierras. Miraculously, Gib would return, but Tobin never could, which disgorged feelings that left us shattered, disintegrating into something that didn’t translate in human terms.

So died the last of our innocence, and innocence was the lifeblood of every Stonemaster. Our pain was nothing compared to the injustice we felt, which left us dismayed and outraged. We surely saw it coming, and Tobin essentially died by his own hand. But I hated God just then. You come into the world believing a brave heart will live forever. When you learn otherwise, you might love once more, but you’ll never again be the same person.

The Stonemasters set a cultural standard aped by monkeys around the world.

Text:

Photos and Photo Editing:

PHOTO ANIMATION/ EDITING

Art Director:

PRODUCED BY:

John Long

Dean Fidelman

Ted Distel

Tyler Hartlage

Delaney Miller

I couldn’t bring myself to attend Tobin’s funeral— something I later deeply regretted—and instead dug out an old Impressions tape and listened to a song that, years earlier, in the tent cabin of a girlfriend in Yosemite, Tobin and I used to play over and over.

People get ready, there’s a train comin’

You don’t need no baggage, you just get on board

All you need is faith to hear the diesels hummin’

You don’t need no ticket, you just thank the Lord

my heart broke.

but when I said goodbye,

free to find the rest of my life,

I was one of the lucky ones

Tobin was the only apostle among us, but this lyric summed up the come-one, come-all philosophy that spread the Stonemasters so far and wide, and saw so many people from so many places just get on board. But in time, the train got too crowded and the nuclear, personal bond that held together our passion and desires slowly unraveled. That’s when I understood that a Stonemaster, in their pure and original form, could only be a kid with a restless spirit and unrequited dreams. And I was no longer a kid with dreams, but a man with stories and skeletons. Grateful? Absolutely. I’d surfed, rather by chance, the critical juncture between cult and culture, had seen the world change before my eyes. But Yosemite and I were done with each other. Suddenly, I stared out over an emptiness so vast it put all my previous encounters with the void into the shade.

A wise friend said that once you know the nature of this emptiness, like an Atlantic squall, you can plot a course through it. Or you can play grab-ass on deck as the winds tear the sails to shreds. The only course I knew was to return to Yosemite, and it only took a few days and a few climbs to know I was playing grab-ass once more.

I went to Vanuatu, Borneo, Irian Jaya, and other places I can’t remember and could never pronounce. Once again, the great unknown provided salvation and spared me the bitterness, dread, and ennui that, following one’s first shattering letdown, drive many into the bottle and into the grave. At long last, I found myself back in The Basement with Richard. It would be our last and shortest confab in our secret castle—Richard soon moved to Red Rock in Nevada and never came back. Almost by reflex, we started in with the stories, though this time, the stories were our own.

French climber Laurent Dubois

Photos and Photo Editing:

Dean Fidelman

PHOTO ANIMATION/ EDITING:

Ted Distel

Produced by:

Delaney Miller

John Long

The slightest misstep and you were off for the big one, and nobody took the big one as often or as dramatically as Tobin Sorenson.

John Bachar, who through natural talent and obsessive dedication, transformed himself into one of the greatest figures in twentieth-century adventure sports.

Julie De Jesus

John Bachar

Presented By

This Short History was Presented By:

Text:

Photos and Photo Editing:

Photo animation/ EdITING:

Produced by:

Art Director:

John Long

Dean Fidelman

Ted Distel

Delaney Miller

Tyler Hartlage

ART DIRECTOR:

Tyler Hartlage

Richard grew up in an artist’s culture (his father was a renowned woodworker) and he developed a shine for alternative lifestyles that seemed so daring that the rest of us wondered how anyone could pull it off and stay out of jail. Each Stonemaster (as we later styled ourselves) brought to the group ingredients that were blended into our collective gestalt. Richard brought the main course: following your own prerogative. If that squared with others—fine. If not, “Tastes differ,” he’d often say, with the coolest aspect you’ve ever seen. Richard went on to climb more routes in more places than most of us combined, always so much on the down-low he might have remained anonymous but for his full-page photo in Meyers’ seminal Yosemite Climber, cranking an early ascent of Nabisco Wall with a young John Yablonski belaying. It’s curious to consider how that picture and the thousand-and-one adventures that followed all sprang from one dark and stormy September night in 1972.

"Falls Away"

"High Infatuation"