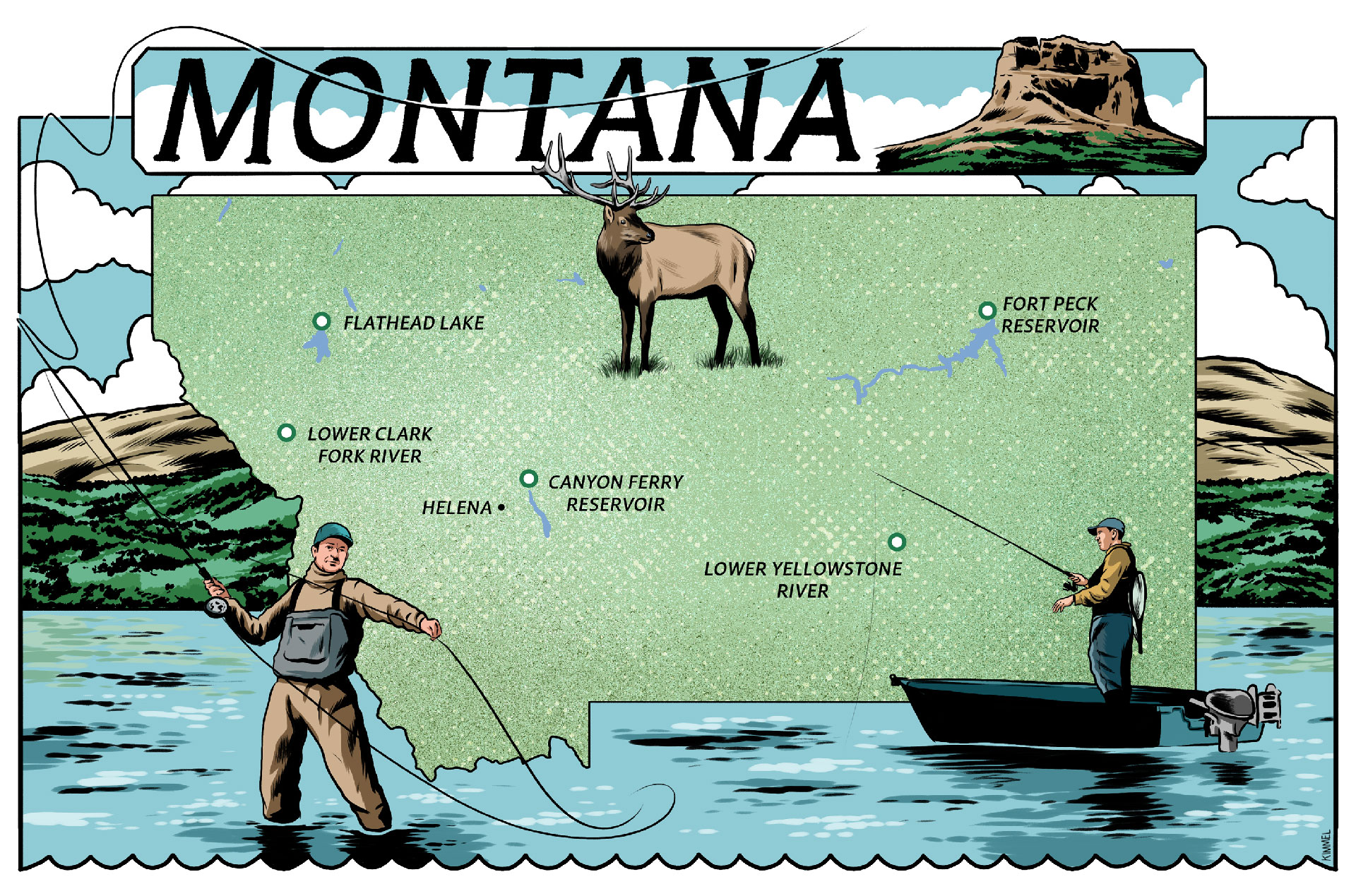

Montana’s �Warmwater �Slam

A roadmap of the Treasure State’s hidden-gem fishing spots.

Montana requires no introduction as a fly-fishing destination for legendary trout fishing. You can’t swing a double-haul floating line without hitting a fly shop or an arm-long rainbow trout.

But the Treasure State is full of lesser-known destinations for other, more overlooked, species, including world-class walleye, northern pike and smallmouth bass. Here’s your roadmap to a Montana warmwater slam, with specific waters and fishing tactics that will leave you enough time to take in some local color and non-fishing landmarks, while allowing you to scratch your trout itch.

Canyon Ferry �Reservoir

This long, narrow lake between Helena and Bozeman — it’s shaped like an elongated eggplant — is the first big impoundment of the Missouri River and was formed in 1954 by the Canyon Ferry Dam. For the first half of its 75-year lifetime, the reservoir was known as a trout destination, a place to catch 3- to 4-pound rainbows on spinning gear and jigs. But in the last 25 years, it’s become a destination walleye fishery, especially in the warmer, shallow southern end.

You’ll want a boat for the best action on eating-size walleye, but patient anglers who jig Canyon Ferry’s depths take limits of tasty yellow perch. And the lake has become a destination for fly fishers who target carp in the hot summer months, catching numbers of 15-pounders they call Rocky Mountain bonefish for their fight and tendency to snub most fly patterns.

The rainbows are still available in the deeper, cooler water of Canyon Ferry, but for numbers of 6- to 10-pound walleye for anglers pulling crankbaits and ‘crawler harnesses, it’s a productive and consistent fishery. Considering the bonus perch bite and a growing number of smallmouth bass, it’s not just for trout anglers anymore.

“

You’ll want �a boat for �the best action �on eating-size walleye...”

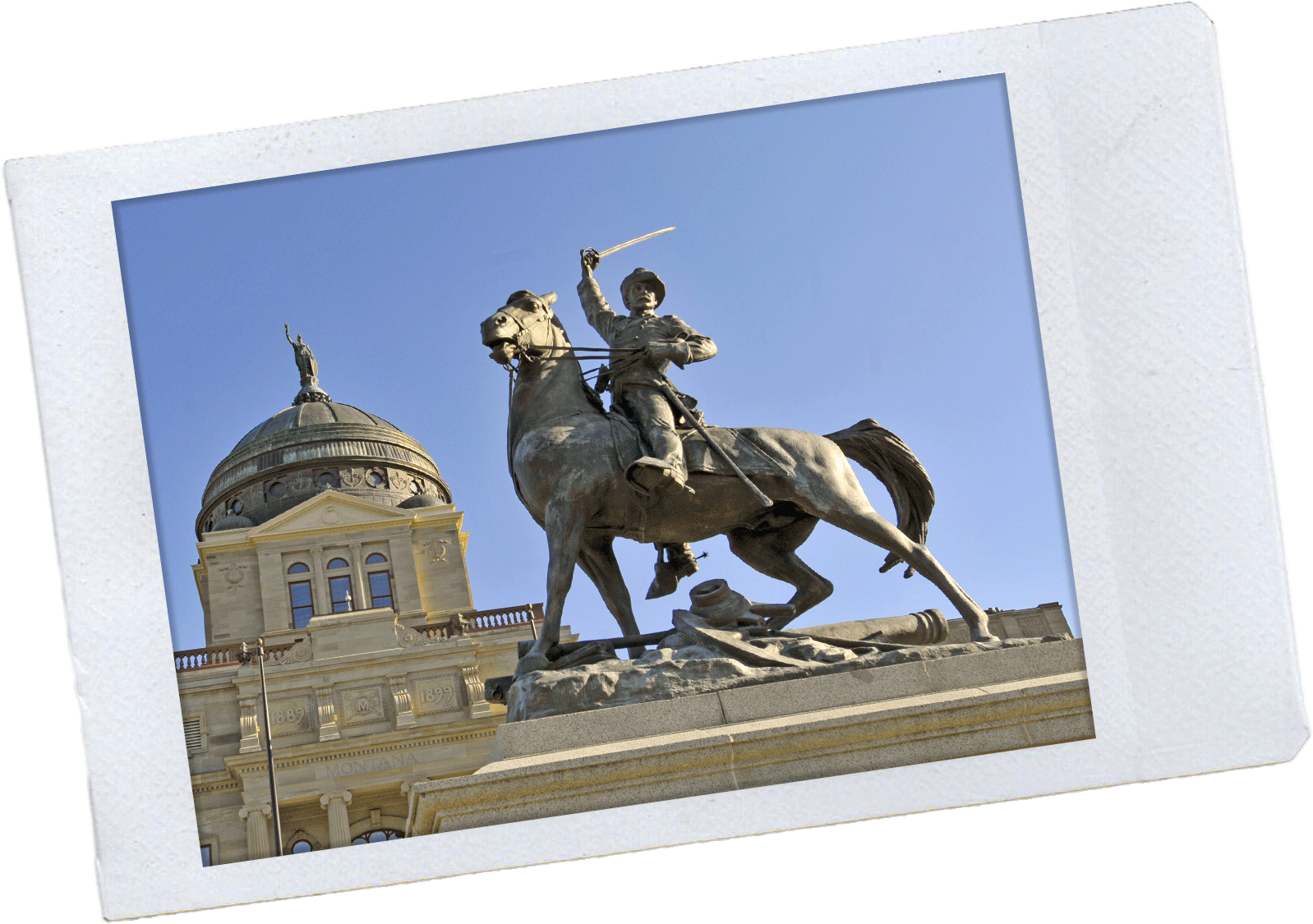

Adjacent Destination

Gates of the Mountains

Just two lakes downstream from Canyon Ferry, on serpentine Holter Reservoir, Gates of the Mountains greets and intimidates visitors just as this natural defile in the Missouri River’s canyon did Lewis and Clark when their Corps of Discovery passed here in July of 1805. The limestone “gates,” which create a sort of optical illusion of opening to admit river (and lake) travelers, are accessible on fishing boats, but also aboard a special boat that offers scenic tours of the Gates and upper Holter Lake. The concession runs late May through mid September and reservations are accepted at Gates of the Mountains.

Lower Yellowstone River

Most visitors to Montana know the Yellowstone River as a gin-clear mountain stream that drains Yellowstone National Park. But downstream of Billings to the North Dakota border, the Yellowstone becomes a roiling, muddy prairie river that’s home to a curious assemblage of fish that most anglers never encounter. The most intriguing might be paddlefish, a species that’s been making springtime spawning runs up Montana’s eastern rivers since dinosaurs walked their shores.

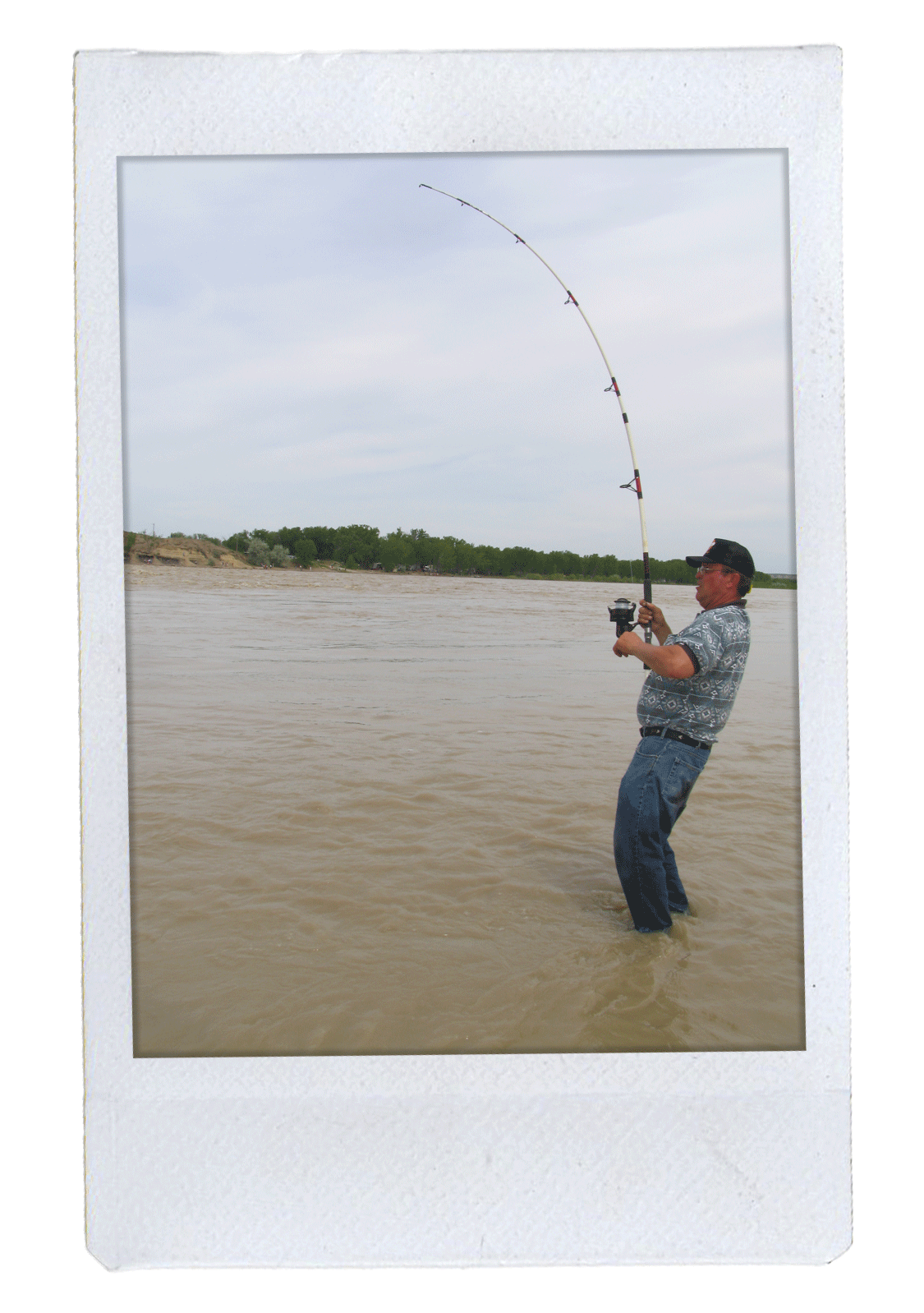

Because paddlefish are filter-straining plankton eaters — think of saltwater right and blue whales — they don’t bite at lures or bait. The only way to catch them is to snag them with big weighted treble hooks, and in the swollen spring flows that trigger their upstream spawning runs, sweeping the river with this heavy hardware is a workout, the angling equivalent of dragging a river for a body.

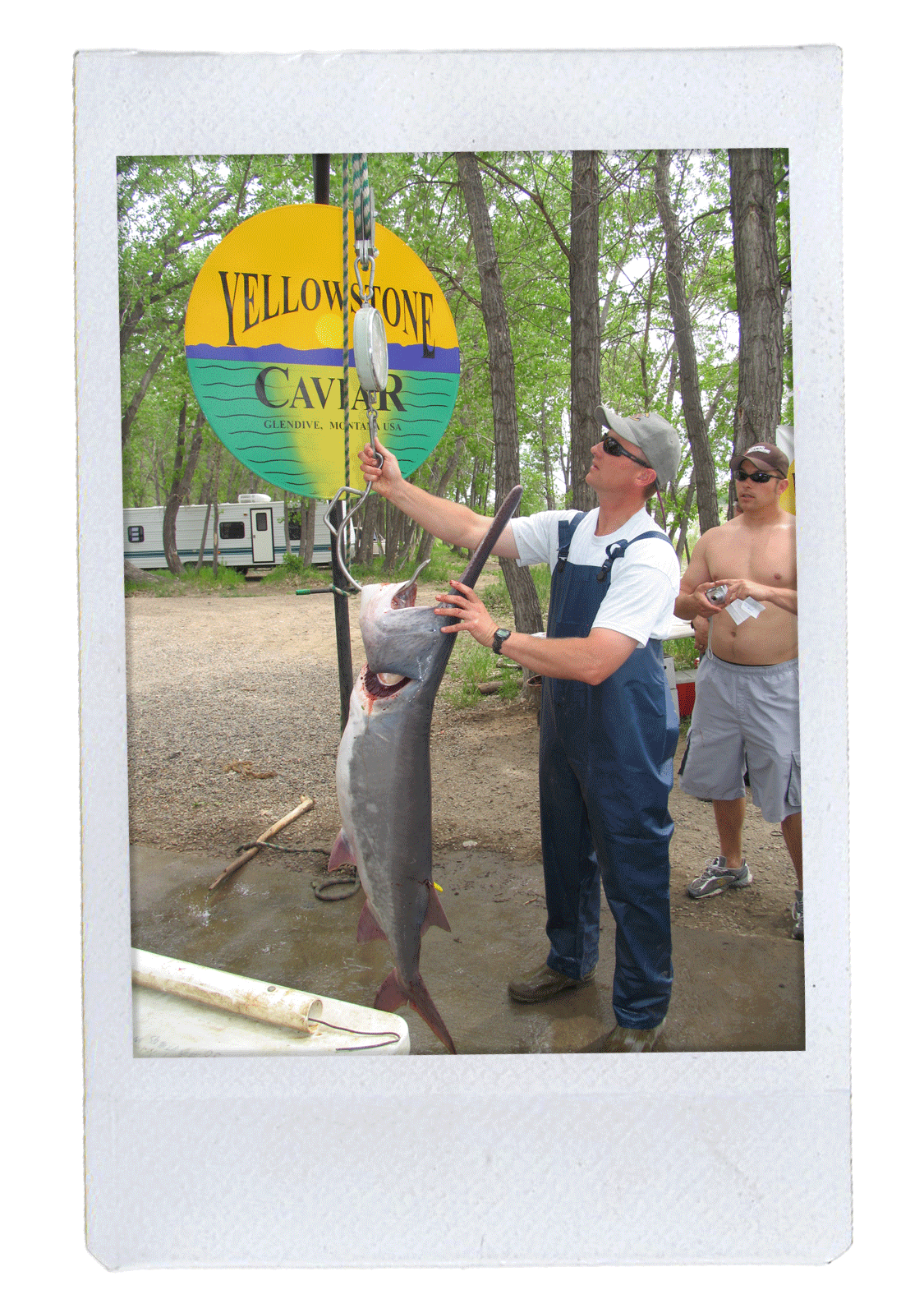

The payoff is a prehistoric fish that can weigh over 100 pounds. Female paddlefish pack pounds of black caviar prized for its culinary contributions, but paddlefish meat is also delectable, similar to cod or snapper when prepared correctly.

While the lower Yellowstone gets lots of attention during springtime paddlefish season, it has an earned reputation for producing large channel catfish, and bait fishers often catch shovelnose sturgeon and a wide variety of native suckers.

Adjacent Destination

Makoshika �State Park

Walk in the footsteps of dinosaurs in this scoured badland, timbered highlands that drop through technicolor canyons toward the river town of Glendive. The headline in this state park is its paleontological wonders, with university-led digs in most seasons, but most locals know it as a killer picnic and hiking spot.

Top: A snagger hooks into a Yellowstone River paddlefish

Bottom: A Montana fisheries biologist weighs a Yellowstone River paddlefish

Fort Peck �Reservoir

The granddaddy of all warmwater fisheries in Montana, the largest reservoir in the state is also its most diverse. Fort Peck is best known for its outrageous walleye fishing — tournament anglers with forward-facing sonar routinely boat 10-fish bags that weigh 100 pounds — but this prairie reservoir is becoming known for its smallmouth bass and northern pike. If you tire of pitching topwater plugs, big plastic creature baits, or pulling crawler rigs, you can troll downriggers for surprisingly big and plentiful lake trout and Chinook salmon. The latter is one of the few landlocked salmon fisheries in the Northern Great Plains.

You’ll want a lake-worthy boat for the best fishing, but land-lubbers can catch bass and pike off the rocks of Fort Peck Dam, and the remote upper end of the reservoir has a surprisingly good crappie population.

Adjacent Destination

Fort Peck Dam

In a part of the state better known for its Angus and hard red winter wheat, the Missouri River below Fort Peck Dam sports a surprisingly reliable rainbow trout fishery. It’s mostly productive for a few weeks in the spring, as football-sized females gather on spawning gravel, but it sustains eastern Montana fly anglers for the rest of the year. Show up on weekends for plays at the Fort Peck Summer Theatre, excellent summer stock productions staged in a Depression-era playhouse.

Trophy Fort Peck Reservoir walleye

Tony Webster from Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States, �via Wikimedia Commons

Flathead Lake

Montana’s largest natural lake, this Glacier Country jewel winks with jade-blue water and immaculate rock-and-sand shorelines. It surprises some visitors with its northern pike fishery, the rival of some Canadian destinations in terms of the size and numbers of these hard-fighting predators. Flathead Lake also has a very good yellow perch population that gets the attention of ice fishers on those rare winters when the southern bays out of Polson freeze over. For the rest of the year, Flathead’s lake whitefish, which grow to 3 and 4 pounds and are excellent smoker fare, take up the slack when the lake’s legendary lake trout aren’t biting.

Adjacent Destination

Thompson Chain of Lakes

Flathead Lake rewards anglers with bigger boats that can navigate the lake’s vast and sometimes choppy waters. If you’re a shore angler with only a rod and a desire to catch supper, head west on U.S. Highway 2 to the Thompson Chain of Lakes. This series of lakes offers the best of Montana’s warmwater fishing, with yellow perch and pumpkinseed panfish in many lakes, smaller northern pike in most and even largemouth bass in others. Thompson Chain of Lakes State Park offers camping, fire rings and lakeside access to many of the productive waters.

Lower Clark �Fork River

The college town of Missoula is a gateway of sorts to the trout-rich Blackfoot and Clark Fork rivers. Despite the best efforts of Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks to keep them out of the river, northern pike have arrived in the lower Clark Fork, and you’re as likely to hook a 25-inch brown trout as you are a 30-inch northern pike in the river from Frenchtown to Plains.

The last miles of the Clark Fork in Montana, an important tributary of the mighty Columbia River, are impounded in Noxon Rapids Reservoir, a destination for tournament anglers on the Pacific Northwest bass circuits. Noxon also has some mighty northern pike in its weedy upper reaches.

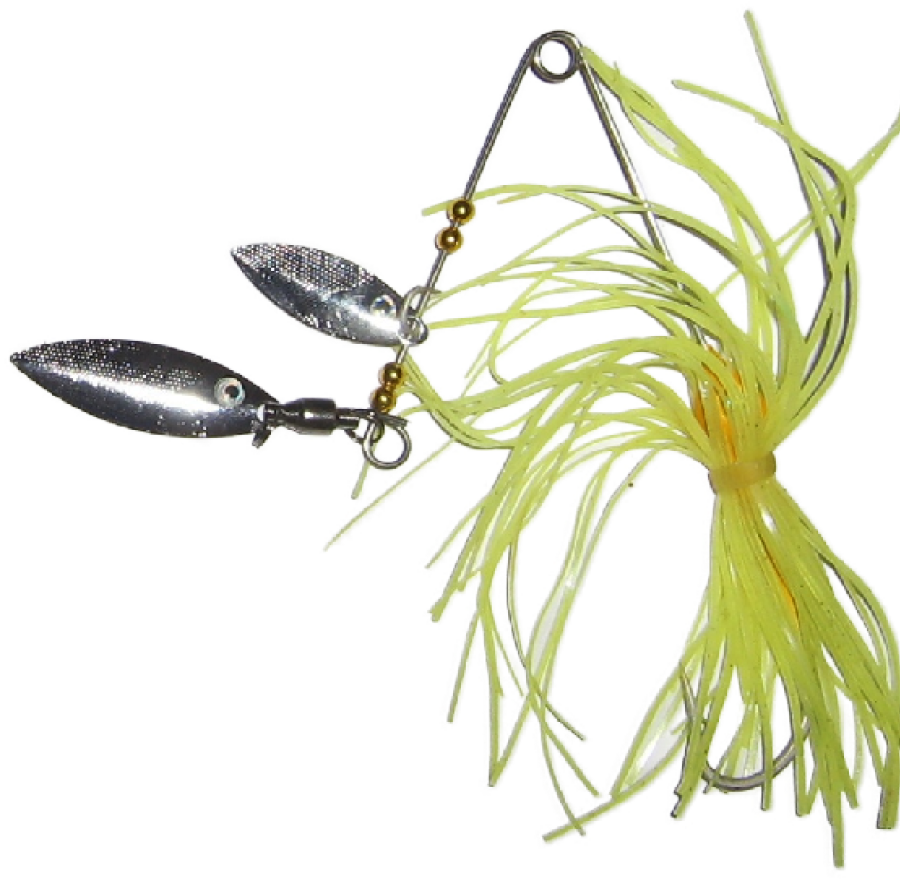

Casting crankbaits and spinnerbaits is a go-to method for northern pike. Smallies can be more selective, but dropshotting wacky worms and jigging with 3-inch plastics is a consistently good method to catch structure-oriented bass.

Adjacent Destination

The CSKT Bison Range

The CSKT Bison Range’s auto tour is a chance to reconnect with some of the West’s iconic mammals from the comfort of your car. This property, now managed by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, was set aside to conserve the remnants of the West’s great bison herds. Because hunting isn’t allowed here, it’s become a refuge for mule deer, bighorn sheep, elk and white-tailed deer, as well as being managed for buffalo.

This long, narrow lake between Helena and Bozeman — it’s shaped like an elongated eggplant — is the first big impoundment of the Missouri River and was formed in 1954 by the Canyon Ferry Dam. For the first half of its 75-year lifetime, the reservoir was known as a trout destination, a place to catch 3- to 4-pound rainbows on spinning gear and jigs. But in the last 25 years, it’s become a destination walleye fishery, especially in the warmer, shallow southern end.

You’ll want a boat for the best action on eating-size walleye, but patient anglers who jig Canyon Ferry’s depths take limits of tasty yellow perch. And the lake has become a destination for fly fishers who target carp in the hot summer months, catching numbers of 15-pounders they call Rocky Mountain bonefish for their fight and tendency to snub most fly patterns.

The rainbows are still available in the deeper, cooler water of Canyon Ferry, but for numbers of 6- to 10-pound walleye for anglers pulling crankbaits and ‘crawler harnesses, it’s a productive and consistent fishery. Considering the bonus perch bite and a growing number of smallmouth bass, it’s not just for trout anglers anymore.

Most visitors to Montana know the Yellowstone River as a gin-clear mountain stream that drains Yellowstone National Park. But downstream of Billings to the North Dakota border, the Yellowstone becomes a roiling, muddy prairie river that’s home to a curious assemblage of fish that most anglers never encounter. The most intriguing might be paddlefish, a species that’s been making springtime spawning runs up Montana’s eastern rivers since dinosaurs walked their shores.

Because paddlefish are filter-straining plankton eaters — think of saltwater right and blue whales — they don’t bite at lures or bait. The only way to catch them is to snag them with big weighted treble hooks, and in the swollen spring flows that trigger their upstream spawning runs, sweeping the river with this heavy hardware is a workout, the angling equivalent of dragging a river for a body.

The payoff is a prehistoric fish that can weigh over 100 pounds. Female paddlefish pack pounds of black caviar prized for its culinary contributions, but paddlefish meat is also delectable, similar to cod or snapper when prepared correctly.

While the lower Yellowstone gets lots of attention during springtime paddlefish season, it has an earned reputation for producing large channel catfish, and bait fishers often catch shovelnose sturgeon and a wide variety of native suckers.

The granddaddy of all warmwater fisheries in Montana, the largest reservoir in the state is also its most diverse. Fort Peck is best known for its outrageous walleye fishing — tournament anglers with forward-facing sonar routinely boat 10-fish bags that weigh 100 pounds — but this prairie reservoir is becoming known for its smallmouth bass and northern pike. If you tire of pitching topwater plugs, big plastic creature baits, or pulling crawler rigs, you can troll downriggers for surprisingly big and plentiful lake trout and Chinook salmon. The latter is one of the few landlocked salmon fisheries in the Northern Great Plains.

You’ll want a lake-worthy boat for the best fishing, but land-lubbers can catch bass and pike off the rocks of Fort Peck Dam, and the remote upper end of the reservoir has a surprisingly good crappie population.

The college town of Missoula is a gateway of sorts to the trout-rich Blackfoot and Clark Fork rivers. Despite the best efforts of Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks to keep them out of the river, northern pike have arrived in the lower Clark Fork, and you’re as likely to hook a 25-inch brown trout as you are a 30-inch northern pike in the river from Frenchtown to Plains.

The last miles of the Clark Fork in Montana, an important tributary of the mighty Columbia River, are impounded in Noxon Rapids Reservoir, a destination for tournament anglers on the Pacific Northwest bass circuits. Noxon also has some mighty northern pike in its weedy upper reaches.

Casting crankbaits and spinnerbaits is a go-to method for northern pike. Smallies can be more selective, but dropshotting wacky worms and jigging with 3-inch plastics is a consistently good method to catch structure-oriented bass.