The story so far of Europe's most�exciting regeneration scheme

Welcome

�

�

We’re enormously proud to have a played a supporting role as the plans have taken shape, and thrilled to be helping to bring them to fruition, since the revised scheme successfully achieved planning approval in June 2024.

This is a key milestone in a project that has already spanned more than seven years for our client Lendlease, and which will take another decade before it is fully realised as a brand-new piece of city with a long, rich heritage.

To celebrate, we invited Lendlease, urban planner Prior + Partners and architect David Kohn to share their reflections on the twists and turns of the journey so far and their aspirations for what Smithfield will become.

Smithfield is a very special project, not just because of its scale and complexity, but because of the great team that Lendlease has assembled and the open, collaborative culture that has been created. And of course, because it’s a chance to make a real difference to Britain’s second city and to bring one of its most important sites back to life.

Matthew Winn�Ridge

�

Contents

�

�

Smithfield is where Birmingham began.

Where will it take us next?

01

The opportunity

02

The evolution of the masterplan

03

Where design meets development

04

Designing a 21st century market

Today, Birmingham’s Smithfield is a 800-year-old marketplace that’s been �left behind by modern trading, a heritage site whose medieval significance �is obscured by layers of development, and an inhospitable concrete desert where no one lives and few are drawn to visit.

It’s also the most exciting development site in the UK, if not Europe.

Smithfield’s origins are the origins of Birmingham itself: in the mid-1100s, Peter de Birmingham was granted the right to hold a weekly cattle and food market in the grounds of his manor house. It grew to become the most successful market in England, and the village in which it took place a thriving town. Today, Birmingham has a population of just over 1 million and an economy that’s worth £18 billion annually.

Plans to reinvent this giant 17 hectare plot have been afoot for over a decade, and it will be another decade before they are fully realised. Developer Lendlease, working with a cast of thousands that includes Ridge as project manager, has secured planning permission for a £1.9 billion scheme with more than 3,000 homes, 9,000 new jobs, open public spaces and a reinvented market at its heart.

The scheme will bring Smithfield back to life and up to date, restoring its historic importance to the founding of the city, and setting it up for a future of enormous potential.

�

It's not often you get to work on a site of this scale, in Britain's second biggest city. It's a virtually unheard-of opportunity

SELINA MASON

Lendlease

The first planning application envisaged a new market square, homes, offices and an outdoor event space, anchored by a large new market complex where the wholesale markets building had stood.

It was submitted in 2022, but Historic England objected. Beneath the concrete slab �of wholesale markets, and beneath the Georgian market hall they had replaced, stood �the medieval manor house of the de Birmingham family – the birthplace of the city. �The historic significance to the city is enormous, Historic England argued.

So Lendlease and its design team went back to the drawing board. During a year �of intense team work and collaboration, they reconfigured the plan and many of the �key buildings.

A masterplan is always a negotiation between competing priorities and physical constraints. At Smithfield, the most important factor turned out to be something that no one could see.

01

The opportunity

02

The evolution of the masterplan

03

Where design meets development

04

Designing a 21st century market

Contents

�

�

01

The opportunity

01

The opportunity

02

The evolution of the masterplan

02

The evolution of the masterplan

03

Where design meets development

03

Where design meets development

04

Designing a 21st century market

04

Designing a 21st century market

INSIGHTS�15 minute�READ

02�How the masterplan took shape

Smithfield present

Birmingham’s original street pattern was disrupted by the construction of the wholesale markets in the 1970s. They have been relocated to the edge of the city, setting the stage for the next phase of Smithfield’s evolution.

�The heart of the city

Smithfield is hyper-connected, close to two major railway stations, a soon-to-arrive high-speed line into London and the iconic Bullring shopping centre. It’s also bounded by China Town, Gay Village and Digbeth districts.

Needs a header here

When Lendlease won the developer competition in 2017, Birmingham City Council had already consulted extensively on its own masterplan, and this became the basis for the original application. It envisaged a new market square, homes, offices and an outdoor event space, anchored by a large new building for the Bull Ring markets, where the wholesale market building had stood.

In the approved application, the event space now sits in that location, its shape reflecting the likely line of the moat. The consolidated markets building has been split into two, and the masterplan rebalanced in order to provide a similar level of residential and commercial space. It’s the fruit of a year of intense team work and collaboration, as Lendlease and the designers reconfigured the plan and completely redesigned key buildings.

Back to the drawing board

Opening up the site was an opportunity to explore some solutions in greater detail, says Sammas Ng, associate director at Prior + Partners, which led the masterplan process. For example, there will be a stepped south-facing seating area, a lawn and fountains that lead to water gardens. “The level change allowed us to incorporate a better green-blue strategy in terms of water retention, but we also explored how we could programme the space with features that would make it unique and interesting.”

The event space in the first masterplan was a slightly awkward triangular shape, requiring landscape architect Field Operations to carry out a range of options studies to understand how it would function both day to day and for different kinds of events. “The new space has a more circular layout, which creates a stronger focus, and you can see quite instinctively how it will work,” says Sammas. He also prefers the geometries of the new streets, which now point towards the spire of the church of St Martin in the Bull Ring. “That’s a key moment in terms of people identifying that they’re in Birmingham. The space becomes something that’s wedged between the icons of the city, that makes you want to come in and explore.”

A public space that spans 800 years

One of the biggest questions for the team was how to reflect the historic importance of the site, in the probable absence of any physical remains. “We think this is where the northern side of the moat might be, but it was probably never constructed other than as an earth ditch, and over time that edge would have moved a lot,” says Selina Mason, director of masterplanning and strategic design at Lendlease. “If they do find anything, it might be very difficult to interpret.” Centuries of construction have churned up the site, so that the ground beneath the concrete slab is a soup of medieval and modern relics, and much in between. “It's a classic bit of Victorian city, so what archaeologists have tended to find is that it's highly fragmented and disturbed.”

In dialogue with Historic England, the team decided the best way to preserve the archaeology, while reflecting Smithfield’s significance, was for the public realm to echo the outline of the moat, bringing people back into the centre of the moat and manor house site. “That takes the pressure off whatever is in the ground, but it also has great value for a city that has often struggled to connect to anything other than the recent past,” says David Kohn, founding director of David Kohn Architects, which won the international design competition to design the market building. “We spent a lot of time debating what it is about history that is meaningful. There are all these moments where you’re in the basement of a shopping centre, and there’s a scratchy glass surface, and you look through it and there’s some condensation and a bit of mouldy stone. There’s not much fun or pleasure in discovering that, whereas I think this will be a really great public space.”

In the revised application, the manor house is the centrepiece, with an event space reflecting the likely line of its moat. The markets building has been split into two, and the masterplan rebalanced in order to provide a similar level of residential and commercial space.

The five-year masterplanning process is itself another phase in Smithfield’s history, and the result bears the marks of many hands for future architectural historians to find. There are one or two peculiarities, where buildings were originally designed for a slightly different outlook, but Selina thinks that these help to make it more authentically urban: “The one thing that contemporary masterplans really struggle to do is to have little odd spaces and knotty bits that are not incredibly rational and simplified.”

EXPLORE�

MATTHEW WINN�Ridge

“It’s the outputs that a scheme like Smithfield brings: the economic benefit and to the quality of life for people in and around the area, and the potential for new jobs, education and skills. It’s also the domino effect: if this scheme is a success, that changes the mindset of other developers, and schemes that may not have been viable are suddenly back on the table because the area has been transformed.”

An interview with Selina Mason, Lendlease's Director of Masterplanning and Strategic Design

I want Smithfield to be the scheme that people beyond the UK are talking about too, as somewhere amazing – in the way that people were talking about HafenCity ten years ago, or Rotterdam before that.

SELINA MASON

Director of Masterplanning and Strategic Design, Lendlease

�What is Lendlease hoping to achieve �at Smithfield?

�What we want to do at Smithfield is create a place that people in Birmingham will think of as theirs, with real character and quality, and where they will feel comfortable and welcome and want to hang out. From the conversations we’ve been having, it's really clear that big swathes of the local population are not that interested in the city centre. They don't see it as relevant to them. So, we want Smithfield to be this glorious, incredible place that people will love and cherish and want to keep on coming back to. In the end, that's what fundamentally underpins development value.

How does good design contribute to �a successful regeneration project?

It’s not about the big picture all of the time – the small decisions are super important too. A lot of them are made probably years before you start to put anything on site, so the challenge on a development that will take 20 years is maintaining that consistency of vision. For example, the

Smithfield feels �like it's waiting for something to happen. This is a great opportunity to bring �the site back into use, �and to bring people �back into where the �city started.

SAMMAS NG

Prior + Partners

04�Designing a 21st century market

Smithfield is where everything comes together. We talked about the market having "a different kind of magic".

DAVID KOHN

David Kohn Architects

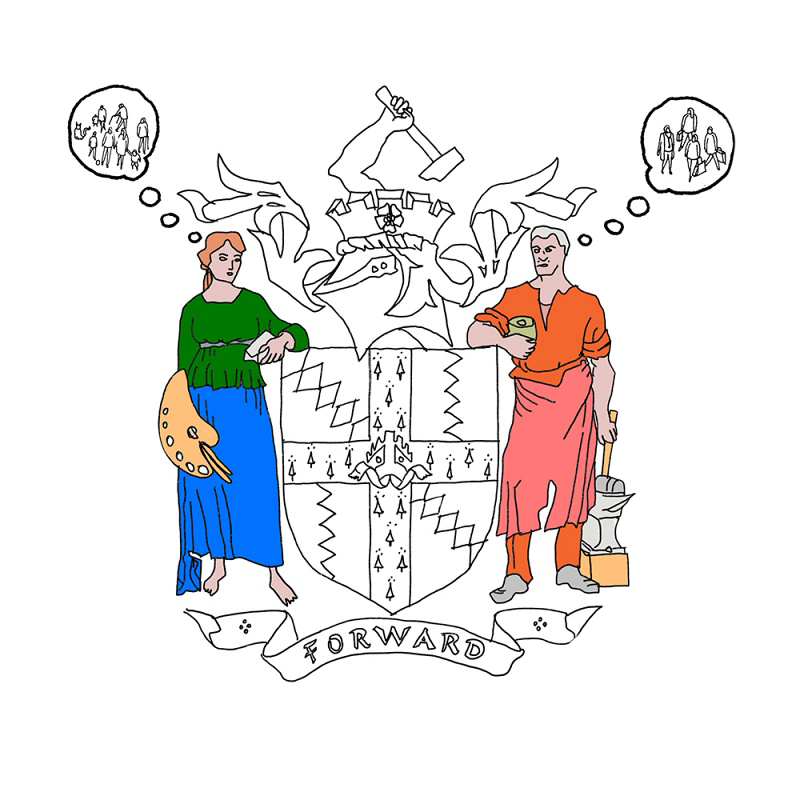

Birmingham’s famous Bull Ring markets will be the anchor of the Smithfield development, as they have been since the founding of the city. David says that one of the inspirations for the design were the two figures on the city’s coat of arms: the artist and the engineer. “The idea that these forces had shaped the city over nearly a thousand years of trade, we wanted to encourage a conversation between these different voices to play out, and somehow bring them together in a joyful convergence.”

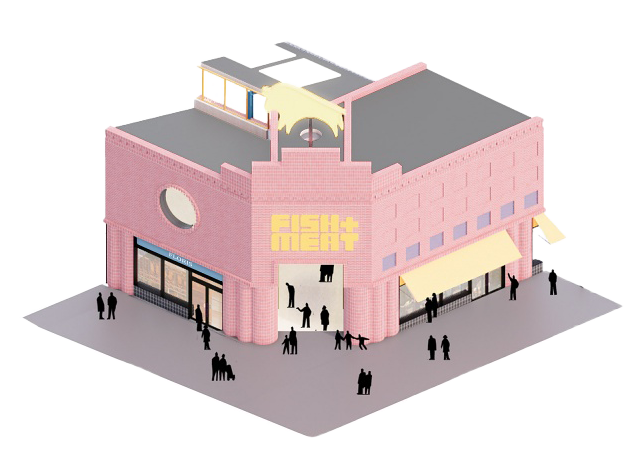

In 2019, David Kohn Architects won an international competition to design a new home for Birmingham’s famous Bull Ring markets. Their challenge was how to reinvent an 800-year-old institution for a very different age.

01�Where Birmingham began

The historic Smithfield site is only a short walk from the Ridge office in Birmingham, but its transformation will be a massive leap forward for the whole city.

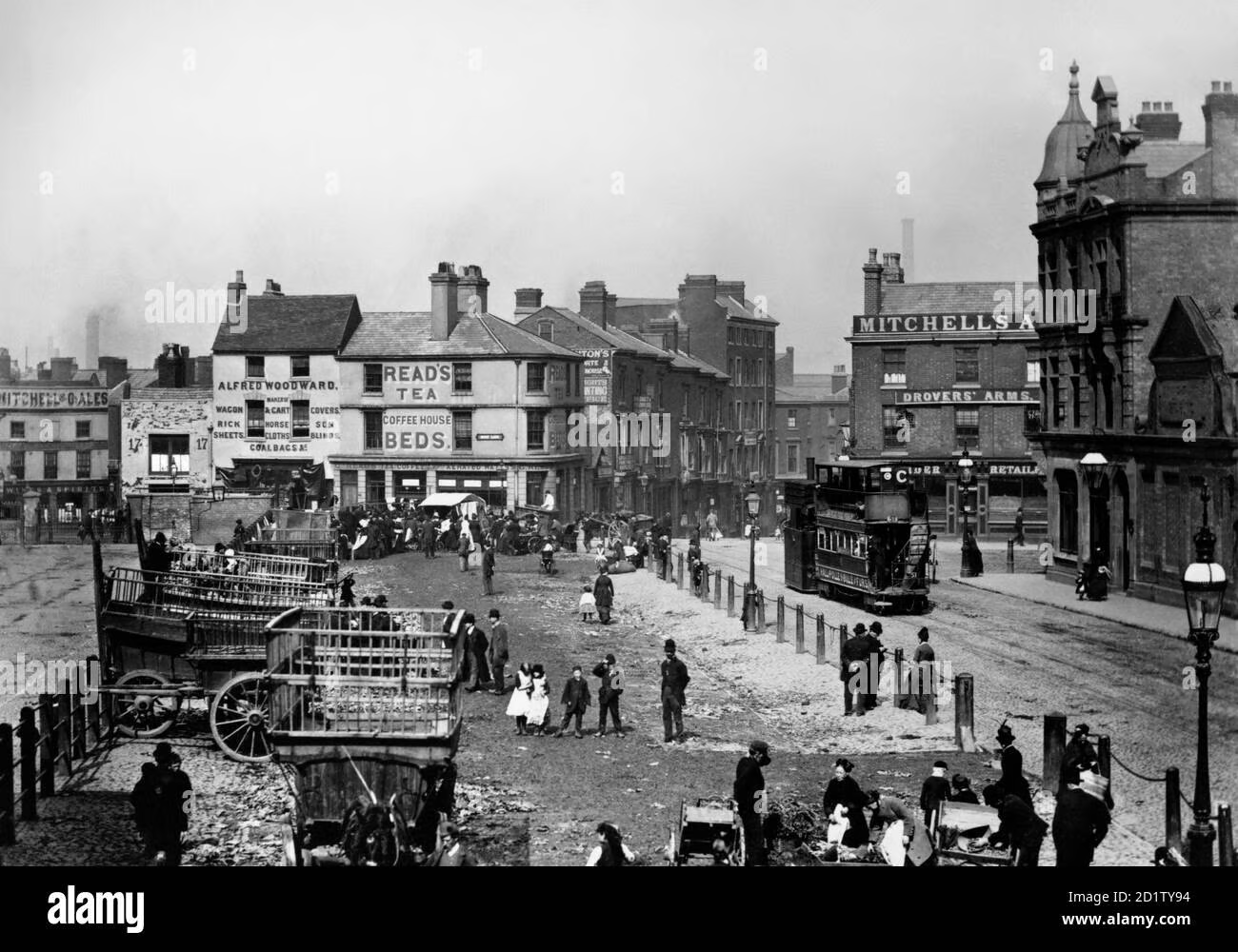

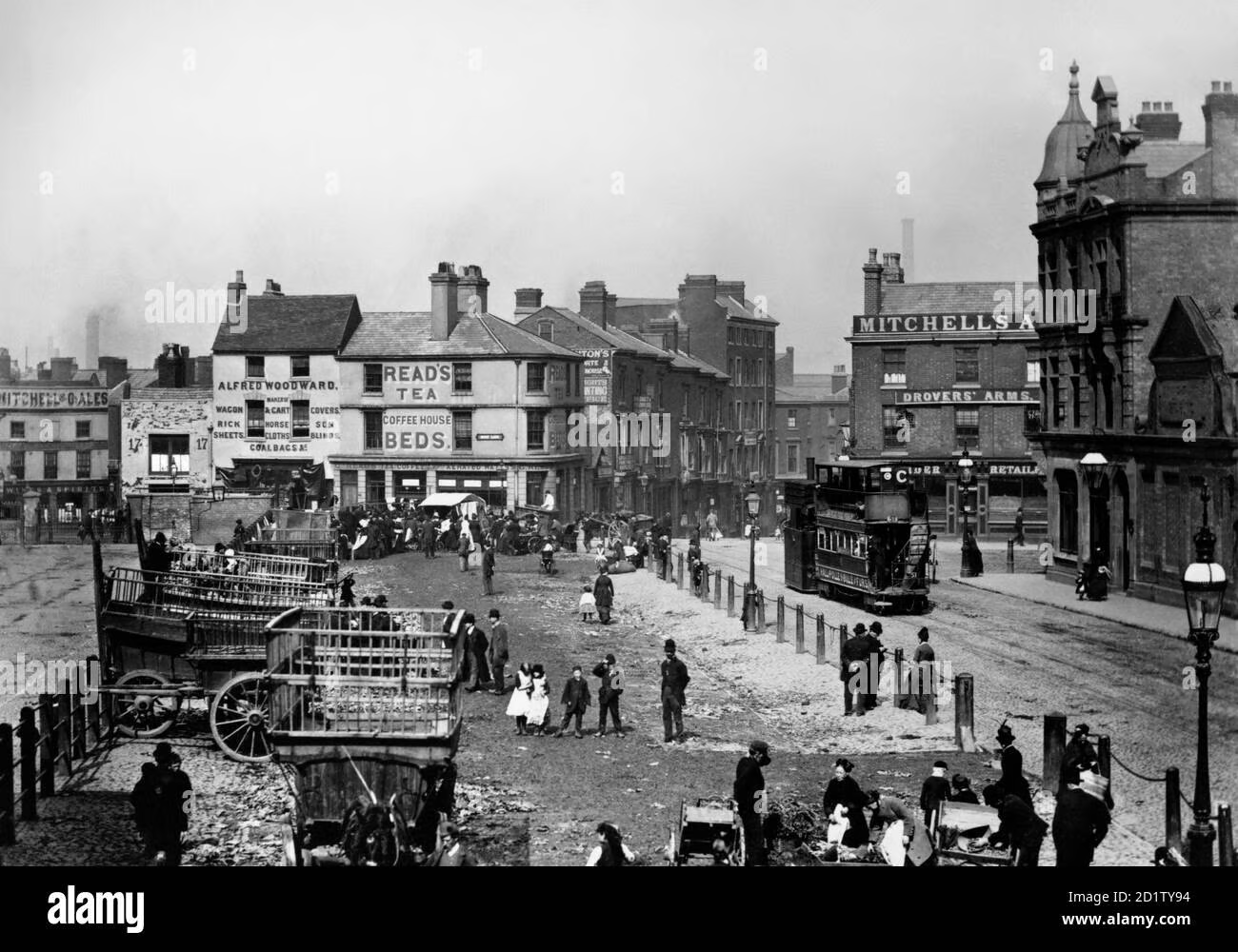

Smithfield past

There has been a market at Smithfield since the mid-1100s. In 1816, the original manor house was demolished and the moat filled in, and a new Smithfield Market opened on the site.

01

02

03

SAMMAS NG

Prior + Partners

“At Smithfield, we have this very unique, super-central location and a lot of ingredients for making a solid part of the city: the market, the cultural building, the new squares. It’s embedded into the context of Birmingham and the mix of uses that already exist, but it also introduces city centre living to really bring life back in. I think that’s an important part of how we can make it successful, thinking about the people who will be using it in the future and how, and creating spaces and ways of using them that will encourage them to come in.”

David Kohn Architects �won the design competition in 2019. One of their early inspirations was the two figures on Birmingham’s coat of arms: the artist and the engineer, says founding director David Kohn. “The idea that these forces had shaped the city over nearly a thousand years of trade, we wanted to encourage a conversation between these different voices to play out, and somehow bring them together in a joyful convergence.”

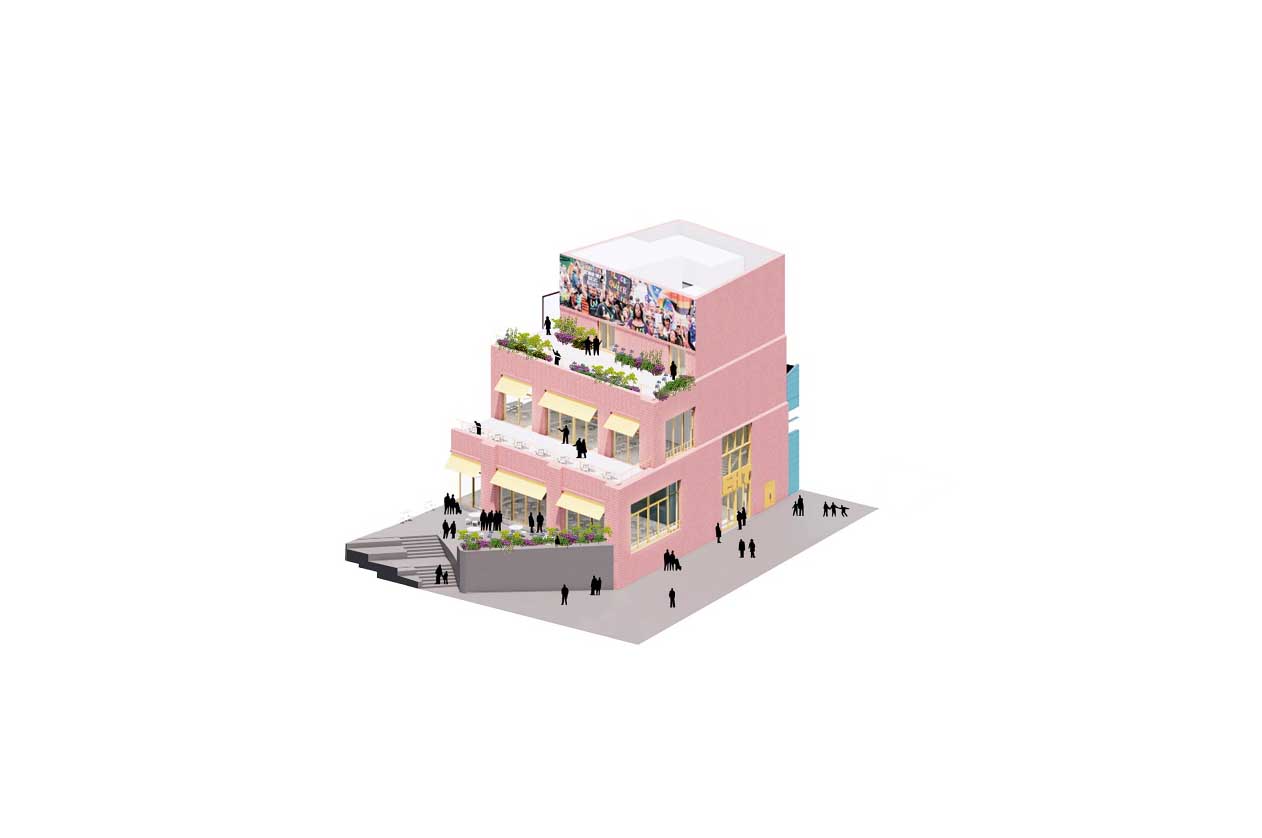

The market building has gone through several iterations. As the centrepiece of the first planning application, it combined a covered outdoor marketplace, dedicated halls for the fish, meat and rag markets, and a food hall, topped with offices and a public rooftop garden. It was conceived as a piece of city in its own right, and a cultural asset as much as a commercial one, with performance and gathering spaces throughout.

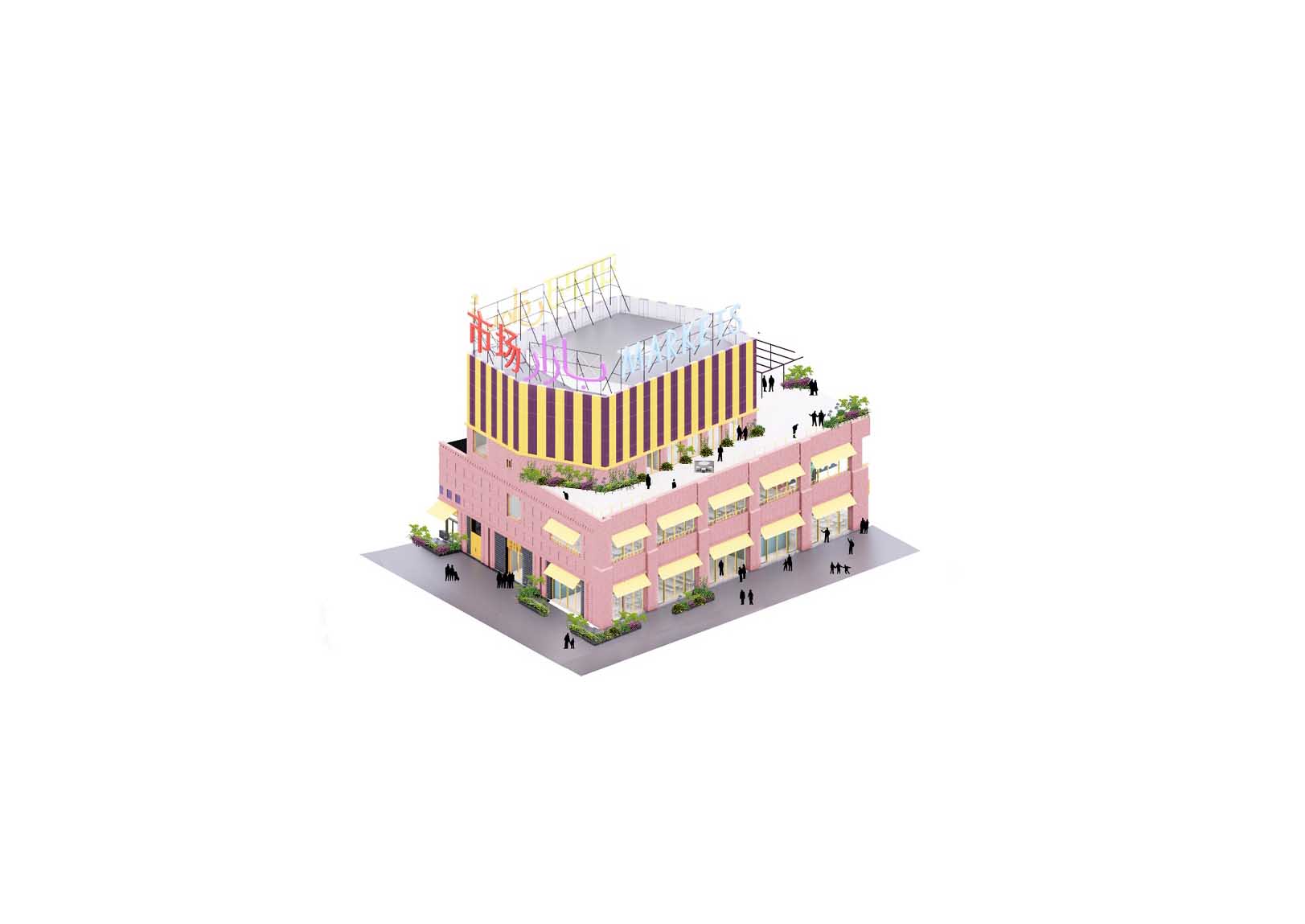

The finalised design is smaller, but no less vibrant. It will contain only the indoor food market, dining hall, restaurant and an event space, with a digital screen to increase its investment value. A second building, yet to be designed, will house the rag market, with the outdoor market taking place a new public square.

“As architects, we're always interested in the city that we're working in, and the contribution the architecture can make,” says David. “Here, I can hand-on-heart say that this building is strongly connected to the public space, and vice versa.”

SELINA MASON

Lendlease

“Regeneration by its very nature tends to be carried out via public-private partnerships. Projects are usually focused on areas where there has been market failure, so you need to galvanise the private sector. One of the hallmarks of a successful scheme is where the clarity of purpose has evolved over time with stakeholders, so that it's a shared vision both between the public and private sector, and the wider stakeholder group.”

01

02

03

01

02

03

01

02

03

04

05

01

02

03

04

05

01

02

03

04

05

01

02

03

04

05

01

02

03

04

05

�Prior + Partners

EXPLORE THE SMITHFIELD SITE

Smithfield future

In 2011, Birmingham City Council announced plans for a 20-year transformation, which will reconnect and revitalise the central core. The Smithfield development is an essential element.

Partner�Ridge and Partners

THE PROJECT MANAGER

Matthew Winn�

Founding Director�David Kohn Architects

THE ARCHITECT

David Kohn

THE MASTERPLANNER

Sammas Ng

Associate Director�Prior + Partners

Director of Masterplanning �and Strategic Design�Lendlease

THE DEVELOPER

Selina Mason

WHO'S WHO AT SMITHFIELD?

"It takes a shared �vision to galvanise the �private sector"

READ MORE

WHAT MAKES A SUCCESSFUL REGENERATION PROJECT?

put a pic of completed project with everything in it�winter wonderland

"Regeneration by its very nature tends to be carried out via public-private partnerships. Projects are usually focused on areas where there has been market failure, so you need to galvanise the private sector. One of the hallmarks of a successful scheme is where the clarity of purpose has evolved over time with stakeholders, so that it's a shared vision both between the public and private sector, and the wider stakeholder group.”

WHAT MAKES A SUCCESSFUL REGENERATION PROJECT?

“At Smithfield, we have this very unique, super-central location and a lot of ingredients for making a solid part of the city: the market, the cultural building, the new squares. It’s embedded into the context of Birmingham and the mix of uses that already exist, but it also introduces city centre living to really bring life back in. I think that’s an important part of how we can make it successful, thinking about the people who will be using it in the future and how, and creating spaces and ways of using them that will encourage them to come in.”

Sammas has led the masterplan and phase one team since 2019.

WHAT MAKES A SUCCESSFUL REGENERATION PROJECT?

“I think success depends on the quality of what’s delivered. You could almost see this planning permission as a new starting point, with many possible implementations. The one that we’d like to deliver and that would be the most successful is the one that has the most quality in how it's made, that achieves a very high quality of finish and material detailing that lasts. It’s an incredibly well-made bit of city, and that's part of the pleasure of being there. It would be amazing if Smithfield set an entirely new benchmark for Birmingham.”

David Kohn Architects won an international competition to design the new market buidling.

WHAT MAKES A SUCCESSFUL REGENERATION PROJECT?

“It’s the outputs that a scheme like Smithfield brings: the economic benefit and to the quality of life for people in and around the area, and the potential for new jobs, education and skills. It’s also the domino effect: if this scheme is a success, that changes the mindset of other developers, and schemes that may not have been viable are suddenly back on the table because the area has been transformed.”

Text for Selina hover pop-up, unless you think click would be better?

Sammas text for pop-up

David text for pop-up

Matt text for pop-up

A public space that spans 800 years

One of the biggest questions for the team was how to reflect the historic importance of the site, in the probable absence of any physical remains. Centuries of construction have churned up the site, so that the ground beneath the concrete slab is a soup of medieval and modern relics, and much in between. In dialogue with Historic England, they decided echo the outline of the moat in the public realm, bringing people back into the centre of the site. “That takes the pressure off whatever is in the ground, but it also has great value for a city that has often struggled to connect to anything other than the recent past,” says David. “We spent a lot of time debating what makes history meaningful. There’s not much fun or pleasure in discovering a bit of old stone in a basement, whereas this will be a really great public space.”

“Create a mix of uses �to encourage people back �into the centre"

READ MORE

"It's all about the �quality of what�we deliver"

READ MORE

“One successful �scheme creates a�domino effect"

READ MORE

Living in the city

The Smithfield will be a completely new residential district in the heart of the city. “From 2000 onwards, cities like Manchester and Liverpool have been completely transformed by people living in the centre,” says Selina. “Birmingham is probably about 20 years behind. There’s an almost completely untapped market.”

You are here

The new streets will point towards the spire of the church of St Martin in the Bull Ring. “That’s a key moment in terms of people identifying that they’re in Birmingham,” says Sammas. “The space becomes something that’s wedged between the icons of the city, that makes you want to come in and explore.”

Immersed within the green

There will be a stepped south-facing seating area, a lawn and fountains that lead to water gardens. “The level change allowed us to incorporate a green-blue strategy in terms of water retention, but we also explored how we could programme the space with features that would make it unique and interesting,” says Sammas.

03�Where design meets development

material palette in Birmingham is really interesting. If you go to the Jewellery Quarter, it's all black brick with pink granite curbs – very practical, very Victorian. That's in our palette too, but I had to argue the case for pink granite curbs and insist on them, because concrete is much cheaper.

You had to do a major redesign of the scheme to win planning approval – any regrets?

I think it's definitely better in terms of public realm. My one regret is that in the previous scheme, we were delivering a very high-powered, high-footfall urban street either side of the larger market building. It would

have been really interesting to have been involved in something like that – I can't think of an equivalent. We’re still delivering plenty of streets, but they're largely residential, and it’s mainly little lanes and ginnels.

It’s been more than seven years since Lendlease won the developer competition. What’s the secret of surviving such a marathon process?

One thing that’s often underappreciated is that creative thinking is really the only way through some of these difficulties. If you've got a major issue with your budget on a building, you can only get so far by chopping bits off or adjusting the materials. You have

to be prepared to think laterally because some things are insurmountable without complete recalibration. You also need to gather a team who love what they do, because it is a long, painful journey and it does get fractious at times. Choosing people who are genuinely excited by the proposition – that's really important.

WHY ARE� MARKETS SO CHALLENGING �IN THE 21ST �CENTURY?

?

HOW DO YOU�DESIGN AROUND�SOMETHING�THAT'S NO�LONGER THERE?

?

Market economics, then and now

Whether you live in a city or you’re just visiting, markets always make for a compelling destination. But they’re a tricky proposition for developers, who build assets to sell rather than to hold: markets generate footfall and memories, but not necessarily commercial value for investors. Markets can be combined with other uses such as office space, although this won’t attract the highest rents, being better suited to creatives than blue-chip corporations. Mixed-use buildings are also more complex, which adds cost. This in turn pushes up the amount of lettable space needed for viability, further increasing complexity and cost.

“If you think about the Victorian era, the great heyday of markets, somewhere between 30-50% of a household’s income would go on food. We don’t spend anywhere near that now, so market buildings don’t make as much economic sense,” says Selina.

WHAT MAKES A SUCCESSFUL REGENERATION PROJECT?

Regeneration by its very nature tends to be carried out via public-private partnerships. Projects are usually focused on areas where there has been market failure, so you need to galvanise the private sector. One of the hallmarks of a successful scheme is where the clarity of purpose has evolved over time with stakeholders, so that it's a shared vision both between the public and private sector, and the wider stakeholder group.

THE DEVELOPER

Selina Mason

At Smithfield, we have this very unique, super-central location and a lot of ingredients for making a solid part of the city: the market, the cultural building, the new squares. It’s embedded into the context of Birmingham and the mix of uses that already exist, but it also introduces city centre living to really bring life back in. I think that’s an important part of how we can make it successful, thinking about the people who will be using it in the future and how, and creating spaces and ways of using them that will encourage them to come in.”

WHAT MAKES A SUCCESSFUL REGENERATION PROJECT?

THE MASTERPLANNER

Sammas Ng

THE ARCHITECT

David Kohn

I think success depends on the quality of what’s delivered. You could almost see this planning permission as a new starting point, with many possible implementations. The one that we’d like to deliver and that would be the most successful is the one that has the most quality in how it's made, that achieves a very high quality of finish and material detailing that lasts. It’s an incredibly well-made bit of city, and that's part of the pleasure of being there. It would be amazing if Smithfield set an entirely new benchmark for Birmingham.”

WHAT MAKES A SUCCESSFUL REGENERATION PROJECT?

THE PROJECT MANAGER

Matthew Winn

It’s the outputs that a scheme like Smithfield brings: the economic benefit and to the quality of life for people in and around the area, and the potential for new jobs, education and skills. It’s also the domino effect: if this scheme is a success, that changes the mindset of other developers, and schemes that may not have been viable are suddenly back on the table because the area has been transformed.”

WHAT MAKES A SUCCESSFUL REGENERATION PROJECT?

A 'Placemaking Pioneers' project story from

FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT

FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT

FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT

FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT

FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT FINAL DRAFT

Smithfield, Birmingham

05

What makes a successful regeneration project?

05

What makes a successful regeneration project?

05

What makes a successful regeneration project?

05

What makes a successful regeneration project?

Visualisation: Lendlease

Illustrative masterplan: Prior + Partners

Photo: Historic England Archive/Heritage Images /Alamy Stock Photo

Photo: Prior + Partners and Tony Jackson

Visualisation: Lendlease

Visualisation: Lendlease

Illustrative masterplan: Prior + Partners and Field Operations

Visualisation: Lendlease

Visualisation: Lendlease

Illustration: David Kohn Architects

Illustration: David Kohn Architects

Visualisation: Lendlease

Visualisation: Lendlease

The story so far of Europe's most�exciting regeneration scheme

Welcome

�

�

We’re enormously proud to have a played a supporting role as the plans have taken shape, and thrilled to be helping to bring them to fruition, since the revised scheme successfully achieved planning approval in June.

This is a key milestone in a project that has already spanned more than seven years for our client Lendlease, and which �will take another decade before �it is fully realised as a brand-new piece of city with a long, �rich heritage.

�

Contents

�

�

06

Smithfield: the future

�

�

To celebrate, we invited Lendlease, urban planner Prior + Partners and architect David Kohn to share their reflections on the twists and turns of the journey so far and their aspirations for what Smithfield will become.

Smithfield is a very special project, not just because of its scale and complexity, but because of the great team that Lendlease has assembled and the open, collaborative culture that has been created. And of course, because it’s a chance to make a real difference to Britain’s second city and to bring one of its most important sites back to life.

Matthew Winn | Ridge

Smithfield is where Birmingham began.

Where will it take us next?

01

The opportunity

02

The evolution of the masterplan

03

Where design meets development

04

Designing a 21st century market

05

What makes a successful regeneration project

CAPTION INTERACTIVE SITE MAP

Today, Birmingham’s Smithfield is a 800-year-old marketplace that’s been left behind by modern trading, a heritage site whose medieval significance is obscured by layers of development, and an inhospitable concrete desert baked by the sun, where no one lives and few are drawn to visit.

It’s also the most exciting development site in the UK, if not Europe.

Plans to reinvent this giant 17 hectare plot have been afoot for over a decade, and it will be another decade before they are fully realised. Developer Lendlease, working with a cast of thousands that includes Ridge as project manager, has secured planning permission for a £1.9 billion scheme with more than 3,000 homes, 9,000 new jobs, open public spaces and a reinvented market at its heart. The scheme will bring Smithfield back to life and up to date, restoring its historic importance to the founding of the city, and setting it up for a future of enormous potential.

As Selina Mason, director of masterplanning and strategic design at Lendlease, says: “It’s not often you get to work on a site of this scale, in a city centre in the UK – and not just any city centre, but Britain’s second biggest city. It’s a virtually unheard-of opportunity.”

Where it all began

Smithfield’s origins are the origins of Birmingham itself: in the mid-1100s, Peter de Birmingham was granted the right to hold a weekly cattle and food market in the grounds of his manor house. It grew to become the most successful market in England, and the village in which it took place a thriving town. Today, Birmingham has a population of just over 1 million and an economy that’s worth £18 billion annually.

But its more recent history begins in 2011, when Birmingham City Council released its Big City Plan for a 20-year transformation of the city. This envisaged the removal of the ring road and much of the traffic, allowing the central core to expand by 25%, improving connectivity, diversifying the economy and foregrounding its unique heritage.

�

Smithfield, then known as the Southern Gateway, was an essential part of the plan. The development of the wholesale markets in the 1970s had disrupted Birmingham’s original street pattern, imposing what the council described as “a fortress-like building that turns it back on the surrounding area”, and blocking access through the site. They have now been relocated to a purpose-built facility on the edge of the city, setting the stage for the next phase of Smithfield’s evolution.

A new piece of city

A reimagined retail market building will be the focal point of the Smithfield development, but there will be completely new elements too. In particular, Selina sees an opportunity to create a residential area, something that’s lacking in the city centre today. Birmingham’s post-war modernist planning favoured demarcated single-function quarters, dedicated to retail or offices or entertainment with very little mixing – out of step with the urban renaissance that’s taken place over the last couple of decades, she says. “From 2000 onwards, cities like Manchester and Liverpool have been completely transformed by people living in them. Birmingham is probably about 20 years behind. People are starting to move in but there’s an almost completely untapped market.”

Smithfield is hyper-connected, she points out, close to two major railway stations, a soon-to-arrive high-speed line into London and the iconic Bullring shopping centre. It’s also bounded by China Town, Gay Village and Digbeth districts, points out Sammas Ng, associate director at urban planner Prior + Partners, who has led the masterplan team since 2019.

“They’re vibrant places in their own right, but Smithfield really feels like it’s the end of the city centre,” he says. “The site is very quiet since the markets left in 2018, and it feels like it’s waiting for something to happen. This is a great opportunity to bring the site back into use, and to bring the public back to where it all started. It’s a very exciting moment for Smithfield, and for Birmingham.”

It's a very exciting moment for Smithfield, and for Birmingham

Sammas NG

Associate Director at urban planner�Prior + Partners

02�The evolution of the masterplan

A masterplan is always a negotiation between different stakeholders, competing priorities, hard physical constraints, and economic and political viability. In the case of Birmingham’s Smithfield, the most influential factor turned out to be something that no one could see.

Beneath the concrete slab of the wholesale markets building, and beneath the Victorian market hall that had previously stood on the site, had been the medieval moat and manor house of the de Birmingham family – and the birthplace of the city.

It was the significance of the moat and manor house that to the refusal of the first planning application, submitted in December 2022, following an objection by Historic England. And it was the moat and manor house that would become the centrepiece of the revised application, which was approved in June 2024.

When Lendlease won the developer competition in 2017, Birmingham City Council had already consulted extensively on its own masterplan, and this became the basis for the original application. It envisaged a new market square, homes, offices and an outdoor event space, anchored by a large new building for the Bull Ring markets, where the wholesale market building had stood.

In the approved application, the event space now sits in that location, its shape reflecting the likely line of the moat. The consolidated markets building has been split into two, and the masterplan rebalanced in order to provide a similar level of residential and commercial space. It’s the fruit of a year of intense team work and collaboration, as Lendlease and the designers reconfigured the plan and completely redesigned key buildings.

Back to the beginning

In fact, when they went back to the drawing board, they discovered that they were back where they had started, almost five years previously.“When we started rethinking the masterplan, we took out the first presentation that we gave to the city council,” says Sammas Ng, associate director at Prior + Partners, which led the masterplan process. “There were three options, and one of them did have a public space over the moat and manor house.”

Opening up the site in this way added new constraints, but it was also an opportunity to explore some solutions in greater detail, he adds. For example, there will be a stepped south-facing seating area, a lawn and fountains that lead to water gardens. “The level change allowed us to incorporate a better green-blue strategy in terms of water retention, but we also explored how we could programme the space with features that would make it unique and interesting.”

The new arrangement makes the relationship between the public space, the market and the church much more legible

david kohn

David Kohn Architects

originally designed for a slightly different outlook, but Selina thinks that these help to make it more authentically urban, and that the scheme is better overall.

“If you were to start with the proposition that the moat and manor house would be a central square within the site, you might have had a slightly different outcome from our current masterplan,” she says. “But actually the one thing that contemporary masterplans really struggle to do is to have little odd spaces and knotty bits that are not incredibly rational and simplified.”

Sammas agrees: “A city is not a perfect place. There are always interesting moments that have come out of the sequence of development, and the way different people think.” The masterplan has been approved, as has the detailed design of the first phase of buildings, but some elements are still in outline, to be developed in the years to come, he points out. “There are pieces that probably need more time to resolve, and that’s an opportunity for future phases as new designers come onboard, and bring new perspectives.”

How the design team used collaboration and teamwork to turn challenges into�opportunities – and deliver an ever better scheme for Birmingham

03�Where design meets development

02�The evolution of the masterplan

An interview with Selina Mason, Lendlease’s Director of Masterplanning and Strategic Design

What is Lendlease hoping to achieve at Smithfield?

What we want to do at Smithfield is create a place that people in Birmingham will think of as theirs, with real character and quality, and where they will feel comfortable and welcome and want to hang out. Because from the conversations we’ve been having, it's really clear that big swathes of the local population are not that interested in the city centre. They don't see it as relevant to them. So, we want to Smithfield to be this glorious, incredible place that people will love and cherish and want to keep on coming back to – in the end, that's what fundamentally underpins development value.

What about you – what legacy would you like to leave?

Actually, for me, I want to knock King's Cross off the list as the UK's best regeneration project. It's been there too long. I want Smithfield to be the scheme that people beyond the UK are talking about too, as somewhere amazing – in the way that people were talking about HafenCity 10 years ago, or Rotterdam before that.

Does Smithfield have any similarities with your developments outside the UK?

There are two in Sydney that seem to have a lot of resonance with what we’re doing. Darling Harbour is very focused on a highly activated public space and repairing connectivity in a city, particularly relative to the impact of poor infrastructure, although it's predominantly commercial. And Barangaroo too, in terms of the activation of the ground floor. But this will be better.

How does good design contribute to a successful regeneration project?

It’s not about the big picture all of the time – the small decisions are super important too. A lot of them are made probably years before you start to put anything on site, so the challenge on a development that will take 20 years is maintaining that consistency of vision.

For example, the material palette in Birmingham is really interesting. If you go to the Jewellery Quarter, it's all black brick with pink granite curbs – very practical, very Victorian. That's in our palette too, but I had to argue the case for pink granite curbs and insist on them, because concrete is much cheaper.

That said, one of the first things I did when I joined Lendlease was tell them to get rid of all the granite in Elephant Park in London. It’s just not the London material, and it’s so impervious – it never changes. There’s a tendency among developers to specify materials that are maintenance-free and completely unweatherable, but I think the city has to be built to weather and have patina and to look lived in. Part of that is that the materials you choose should have a kind of natural life. They have to be enduring, but not to the extent that they don’t ever change.

And actually you want to see people maintaining the public realm in a city centre. It's a good thing to have some staff out and about, whether they’re cutting the grass or trimming the hedges or occasionally replacing the odd bit of sandstone that might have weathered a little bit too much.

You had to do a major redesign of the scheme to win planning approval – any regrets?

I think it's definitely better in terms of public realm. My one regret is that in the previous scheme, we were delivering a very high-powered, high-footfall urban street either side of the larger market building. It would have been really interesting to have been involved in something like that – I can't think of a equivalent. We’re still delivering plenty of streets, but they're largely residential, and it’s mainly little lanes and ginnels because the new public square has only got tiny bits of city centre streets meeting it.

It’s been more than seven years since Lendlease won the developer competition, and work onsite is only just beginning – what’s the secret of surviving such a marathon process?

One thing that’s often underappreciated is that creative thinking is really the only way through some of these difficulties. If you've got a major issue with your budget on a building, you can only get so far by chopping bits off or adjusting the materials. You have to be prepared to think again and to be lateral in your thinking. So I think creative thinkers are deeply fundamental, and we don't celebrate that enough.

We get very fixated on process and project management instead. But the best project managers are the ones that appreciate that there's a dialogue between the creative endeavour and the process. You don’t get to an outcome without unleashing creative thinking because some of the difficulties along the way are insurmountable without complete recalibration.

You also need to gather a team who enjoy what they're doing too, because it is a long, painful journey and it does get fractious at times. Being able to choose people who are excited by the proposition and genuinely love what they do – that's really important.

I want Smithfield�to be the scheme�that people �beyond the UK�are talking about�too, as somewhere�amazing

04�What makes a successful design project

Four perspectives from the Smithfield team

SELINA MASON

Lendlease

Regeneration by its very nature tends to be carried out via public-private partnerships. Projects are usually focused on areas where there has been market failure, so you need to galvanise the private sector. One of the hallmarks of a successful scheme is where the clarity of purpose has evolved over time with stakeholders, so that it's a shared vision both between the public and private sector, and the wider stakeholder group.”

05�Designing a 21st century market

Birmingham’s famous Bull Ring markets will be the anchor of the Smithfield development, as they have been for the last 800 years. On the one hand, this is a golden opportunity: whether you live in a city or you’re just visiting, markets always make for a compelling destination. But markets are a tricky proposition for developers, who build assets to sell rather than to hold: they generate footfall and memories, but not necessarily hard commercial value for investors.

That was the conundrum that Lendlease faced, explains Selina Mason, director of masterplanning and strategic design. “If you think about the Victorian era, the great heyday of markets, somewhere between 30-50% of a household’s income would go on food,” she says. “We don’t spend anywhere near that now, so market buildings don’t make as much economic sense as they used to.”

Why are markets so challenging?

To make them stack up financially, markets can be combined with other uses such as commercial offices, although the resulting space will be better geared to creatives than blue-chip corporations: “It would be quite simple, certainly not Grade A, and of course that’s going to attract lower rent.”

A mixed-use building is also more complex, which in turn adds cost and increases the amount of lettable space required for viability. “In many respects, it’s kind of arms race between complexity and economics,” she adds.

For David Kohn, founding director of David Kohn Architects, it was the multifaceted nature of the market building that made it so exciting. “The site feels like it’s many different things – there’s the historic church, the vestiges of industry, the Gay Village, the Chinese quarter – and there was this feeing that it’s where everything comes together,” he explains. “In our first proposal, we talked about the market having “a different kind of magic”, which came out of a conversation with Gavin Wade, director of Eastside Projects, a local gallery. It was Gavin’s description that really excited the team.”

Their other inspiration were the two figures on the city’s coat of arms: the artist and the engineer. “The idea that these forces had shaped the city over nearly a thousand years of trade, we wanted to encourage a conversation between these different voices to play out, and somehow bring them together in a joyful convergence.”

Two planning applications, two very different market buildings

The practice won the design competition in 2019, and the design has gone through several iterations since those early sketches, initially growing to include more office space, and then shrinking and shifting location.

The consolidated markets building that was the centrepiece of the first planning application combined a covered outdoor marketplace, dedicated halls for the fish, meat and rag markets and a food hall, topped with offices and a public rooftop garden. It was conceived as a piece of city in its own right, and cultural asset as much as a commercial one, with thoroughfares and spaces for gathering and performances throughout, and works by local artists. “It was very cosmopolitan, very ambitious and it almost made you think of somewhere like Hong Kong, where you expect things to be on different levels,” says David.

The building was also very complex, with layers of different uses. But ultimately, it wasn’t economics that prompted a rethink, but history.

The markets building was to occupy the same plot as the existing wholesale market, but this was also the site of the de Birmingham family’s moat and manor house – the birthplace of the city. When the first planning application was refused due to an objection from Historic England, the masterplan was reconfigured so that the public realm echoed the original line of the moat. The market building had to move, and to split into two.

The building that’s part of the approved masterplan is smaller, but no less vibrant, described by the practice as a “colourful and lively destination with a distinct day and night-time feel”. It will contain only the indoor food market, dining hall, restaurant and an event space. “It does sit much more comfortably in the city,” says Selina. “Now it is literally a standalone market with a dining hall – and it has a digital screen on it, which lifts it into being investable.” A second building, yet to be designed, will house the rag market, with the outdoor market in a new public square.

It’s been a long journey since that design competition win, but David is happy with the market building that’s emerged. “As architects, we're always interested in the city that we're working in, and what contribution the architecture is making. You hope to make strong connections to adjacent spaces, but you can only advocate, you can't control it directly. Here, I can hand-on-heart say that this building has a lot to do with the public space, and vice versa.”

How do you reinvent an 800-year-old institution for a very different commercial landscape? Lendlease and David Kohn Architects discuss their flagship market building for the Smithfield site

The markets are a huge opportunity to create somewhere the whole region can come together

06�Smithfield: The future

Next steps in the development, and the overall timeline for delivery

06

Smithfield: the future

�

�

01

The opportunity

02

The evolution of the masterplan

03

Where design meets development

04

Designing a 21st century market

05

What makes a successful regeneration project

Contents

�

�

06

Smithfield: the future

�

�

06

Smithfield: the future

�

�

01

The opportunity

01

The opportunity

02

The evolution of the masterplan

02

The evolution of the masterplan

03

Where design meets development

03

Where design meets development

04

Designing a 21st century market

04

Designing a 21st century market

05

What makes a successful regeneration project

05

What makes a successful regeneration project

01

02

03

01

02

03

01

02

03

Icons of the city

The event space in the first masterplan was a slightly awkward triangular shape, requiring landscape architect Field Operations to carry out a range of options studies to understand how it would function both day to day and for different kinds of events. “The new space has a more circular layout, which creates a stronger focus, and you can see quite instinctively how it will work.” He also prefers the geometries of the new streets, which now point towards the spire of the church of St Martin in the Bull Ring. “That’s a key moment in terms of people identifying that they’re in Birmingham. The space becomes something that’s wedged between the icons of the city, that makes you want to come in and explore.”

Of course, one of the biggest questions for the team was how to reflect the historic importance of the site, in the probable absence of any physical remains. “We think this is where the northern side of the moat might be, but it was probably never constructed other than as an earth ditch, and over time that edge would have moved a lot,” says Selina Mason, director of masterplanning and strategic design at Lendlease. “If they do find anything, it might be very difficult to interpret.” Centuries of construction have churned up the site, so that the ground beneath the concrete slab is a soup of medieval and modern relics, and much in between. “It's a classic bit of Victorian city, so what archaeologists have tended to find is that it's highly fragmented and disturbed.”

A public space that spans 800 years

In dialogue with Historic England, the team decided the best way to preserve the archaeology, while reflecting Smithfield’s significance, was for the public realm to echo the outline of the moat, bringing people back into the centre of the moat and manor house site. “That takes the pressure off whatever is in the ground, but it also has great value for a city that has often struggled to connect to anything other than the recent past,” says David Kohn, founding director of David Kohn Architects, which won the international design competition to design the market building. “We spent a lot of time debating what it is about history that is meaningful. There are all these moments where you’re in the basement of a shopping centre, and there’s a scratchy glass surface, and you look through it and there’s some condensation and a bit of mouldy stone. There’s not much fun or pleasure in discovering that, whereas I think this will be a really great public space.”

The five-year masterplanning process is itself another phase in Smithfield’s history, and the result bears the marks of many hands for future architectural historians to find. There are one or two peculiarities, where buildings were originally designed for a slightly different outlook, but Selina thinks that these help to make it more authentically urban, and that the scheme is better overall.

“If you were to start with the proposition that the moat and manor house would be a central square within the site, you might have had a slightly different outcome from our current masterplan,” she says. “But actually the one thing that contemporary masterplans really struggle to do is to have little odd spaces and knotty bits that are not incredibly rational and simplified.”

Sammas agrees: “A city is not a perfect place. There are always interesting moments that have come out of the sequence of development, and the way different people think.” The masterplan has been approved, as has the detailed design of the first phase of buildings, but some elements are still in outline, to be developed in the years to come, he points out. “There are pieces that probably need more time to resolve, and that’s an opportunity for future phases as new designers come onboard, and bring new perspectives.”

SELINA MASON

Lendlease

Regeneration by its very nature tends to be carried out via public-private partnerships. Projects are usually focused on areas where there has been market failure, so you need to galvanise the private sector. One of the hallmarks of a successful scheme is where the clarity of purpose has evolved over time with stakeholders, so that it's a shared vision both between the public and private sector, and the wider stakeholder group.”

SELINA MASON

Lendlease

Regeneration by its very nature tends to be carried out via public-private partnerships. Projects are usually focused on areas where there has been market failure, so you need to galvanise the private sector. One of the hallmarks of a successful scheme is where the clarity of purpose has evolved over time with stakeholders, so that it's a shared vision both between the public and private sector, and the wider stakeholder group.”

SELINA MASON

Lendlease

Regeneration by its very nature tends to be carried out via public-private partnerships. Projects are usually focused on areas where there has been market failure, so you need to galvanise the private sector. One of the hallmarks of a successful scheme is where the clarity of purpose has evolved over time with stakeholders, so that it's a shared vision both between the public and private sector, and the wider stakeholder group.”

INSIGHTS

PROJECT MILESTONES

01�The Opportunity

The historic Smithfield site� is only a short walk from the Ridge office in Birmingham, but its transformation will �be a massive leap forward

for the whole city.

Birmingham