Too much ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun or sunbeds can damage skin cells, and causes most cases of skin cancer. Anywhere on the skin can be affected, but it’s typically found on areas exposed to sunlight.

How does it start?

Anyone can get sunburnt or develop skin cancer. But some people have a higher risk. This includes people with light skin, those with lots of moles or freckles, or a history of sunburn.

Who’s affected?

Non-melanoma cancers don’t usually spread and are the easiest forms to treat. Around 1,300 people died in 2016 from this form of skin cancer. Melanoma skin cancer is the most serious type of skin cancer, and can have the ability to spread down through the layers of the skin and to other organs of the body. It begins in the melanocytes cells present in the bottom layer of our epidermis. There are around 16,000 new cases of melanoma skin cancer each year in the UK, of which 86 per cent are preventable. It is most common in older people, with the highest rates in 85-89 year-olds. Over a quarter of new cases are found in those aged 75 and over. Survival varies depending on what stage the cancer has been diagnosed and the patient’s overall health history. For stage one melanoma, the least advanced stage, nearly everyone survives their disease for a year or more in England. Stage four, the most advanced stage, one year survival drops to 51 per cent in women and 48 per cent in men. However, survival is improving thanks in part to advancements in treatments funded by organisations such as Cancer Research UK and increased awareness and earlier diagnosis as a result of public health campaigns.

How serious is it?

The treatment timeline:

Charting cancer successes within living memory

1935

The perils of over-exposure

1992-1999

Flicking the immune switch

T cells are a type of immune cell that goes around the body scanning for any abnormalities, including cancer cells. But cancer cells can often trick the T cell into believing they are normal. In 1992 researchers in Japan discovered a molecule on the T cell called PD-1. Seven years later a lab in the US state of Minnesota

discovered that cancer cells have high levels of a molecule called PD-L1 which “shakes hands” with PD-1 on the T cell. This breakthrough started a race to develop drugs to interrupt the handshake between the two molecules and allow T-cells to attack tumours.

2002

Sequencing cancer genes for greater understanding

Michael Stratton, along with colleagues Richard Wooster and Andy Futreal, lead this bold experiment at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and The Institute of Cancer Research to sequence all of the human genes in cancer samples in order to identify damaged

genes. The purpose of the research was to better understand how these faulty cancer genes affect different types of cancer, and to trace the effects back in order to develop new treatments.

2009

Multiple gene mutations identified in melanoma patients

Seventy-five years on from original reports into sun and UV damage, analysis of DNA from people with advanced melanoma reveals signature genetic damage caused by UV, further underlining the crucial role of skin protection to prevent skin cancer.

The signature was found by researchers at The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK, who analysed the entire DNA from a melanoma cell, and a healthy cell in a person with melanoma.

The researchers found that the melanoma cell contained more than 33,000 mutations compared with the healthy cell and saw evidence of how the cells had tried to repair their damaged DNA. By studying the context of each individual mutation, the researchers confirmed the theory that cancer occurs when multiple key cellular processes become damaged over time, rather than any one individual incidence. These data led the way for researchers to reconstruct what led to melanoma cancer in the first place.

People slowly start to become conscious of the effects of sun exposure, with the first sunscreen created in 1928. In 1935, Cancer Research UK is among the first to issue a public warning about the

links between UV and sun exposure and skin cancer.

Treatment at this point is still limited to localised and disfiguring surgery on visibly affected areas.

My skin cancer journey

54-year-old Adrian was given a year to live following his diagnosis with stage four melanoma. That was before his oncologist suggested he try a groundbreaking new treatment

Adrian’s wife noticed a mole on his back had changed colour, so she encouraged him to visit his GP. The mole was removed and a biopsy shortly after found melanoma.

“I found out over the telephone in a phone call a week later. It was 5pm and I was on my own in my office,” Adrian explains. He was 47 at the time, and had lost his twin brother just seven years ago. “My family were hurting so badly because they had no control of the outcome. My mother was in shock, especially so soon after losing my brother, and my wife simply thought she was going to lose her husband,” he says.

Adrian was rushed to Birmingham City Hospital and within a matter of days had an eight-inch piece of skin tissue removed. Ten days later, he discovered a lump under his left armpit. Despite a 20-day radiotherapy treatment, five golf-ball sized lumps

‘I could be at home

for my children

while I was treated’

appeared on his chest months later. The diagnosis was stage four cancer in his lungs, liver, bowel, and spine. Adrian was told he had less than a year left to live. Dr Neil Stevens, a melanoma specialist, suggested an immunotherapy trial funded by Cancer Research UK.

“Because this was an early-stage trial that was trying to find out about doses and side effects, no one knew how much of the drug the body could take. At first, the dose I was given was too high, causing my pituitary gland to be stressed and expanded,” Adrian explains. Nonetheless, while immunotherapies don't work for everyone, the treatment was successful in further reducing the cancer.

The funding of the immunotherapy trial came from Cancer Research UK. “I owe them my life,” says Adrian, who is now cancer-free and has recently celebrated his 54th birthday with his family.

“This journey has variations of shock that you have to accept and overcome. My oncology team were, and still are, an amazing support to both me and my wife. I will take certain drugs all of my life. However, I’m blessed with life. I feel amazing.”

2017

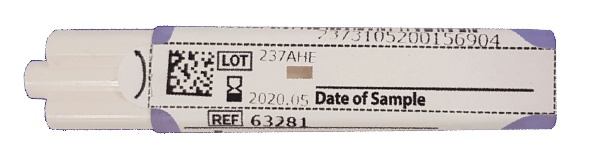

IMPROVED HOME BOWEL SCREENING TEST

The Faecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) detects the blood protein haemoglobin in a poo sample so it can show up microscopic amounts of blood, a warning sign of bowel cancer. It’s now replacing the previous home screening test for people over 60 (50 in Scotland) that was introduced in 2006.

FIT is an improvement on the previous test as it can determine the amount of blood present, rather than just detect if it’s there. It’s also specific to

human blood, so haemoglobin that comes from eating meat won’t produce a false positive. Plus, it’s much less fiddly to perform than the old test as you only need to take one poo sample rather than multiple. Cancer Research UK has played a key part in the rollout of FIT, giving guidance on how the programme should be set up, including advice on setting the thresholds for further testing.

RECEIVED ONE OF THESE IN THE POST?

WHAT IS IT?

Everyone over 60 (50 in Scotland) who is registered with a GP will receive a FIT test (Faecal Immunochemical Test) in the post.

It consists of a small plastic container with a stick attached to the lid.

WHAT DO I DO WITH IT?

Your kit will come with instructions but to put it simply, you just scrape the tip of the stick along your poo, put it back in the bottle and pop it in the freepost packaging for return to the lab.

WHAT DOES THE NHS DO WITH IT?

The sample will be tested to see if there is any blood present. If you have an abnormal result, your GP will be informed and will contact you for further tests.

SHOULD I TAKE PART IN BOWEL SCREENING?

Detecting cancer at an early stage can increase the chances

of survival, but the decision to take part in screening is a personal one. Your bowel screening kit will come with information on the benefits and harms of taking part and you can also visit the Cancer Research UK website for more information.

MY TEST DOESN’T LOOK LIKE THAT.

The new FIT test is being rolled out across the country at slightly different times, so you may have the older kit, known as the gFOBT (guaiac faecal occult blood test). This test is very similar but requires you to send multiple samples instead of one. If you want to take part in screening, don’t wait for a new test, as you won’t automatically be sent the new FIT test until your next invitation in two years time.

Diagnosis: know the symptoms

There is no need to do regular skin checks but do get to know what your skin normally looks and feels like. This means you can spot changes to your skin more easily.

Skin cancer symptoms aren’t limited to changes in moles. It can present itself as a painful or sore itchy spot, sore, ulcer, or lump. Even if you notice a change that isn’t on this list, talk to your doctor.

See your GP if you notice any changes to your skin that don’t go away. It may not be skin cancer, but another condition.

What to look for

A spot or sore

that doesn't heal

A spot or sore that hurts, is itchy, crusty, scabs over, or bleeds

Areas where the skin has broken down (an ulcer) and doesn't heal

Any other changes to your skin that aren’t normal for you

Prevention

Reduce your risk by combining each of these strategies

Cover up

Wear clothing and hats when the UV is 3 or above. From April to September in the UK, UV rays are strongest between 11am and 3pm. To protect your eyes, wear sunglasses that have UV 400 and 100 per cent UV protection.

Stay in the shade

One of the best ways to protect your skin from the sun’s UV rays is to spend some time in the shade. You can find or create shade in many ways. Take a break under trees, umbrellas, canopies or head indoors.

Use SPF

Use sunscreen on the parts of your skin that aren’t covered, but bear in mind that sunscreen will not completely protect you from UV rays and the sun. Cancer Research UK recommends that you choose a sunscreen that has an SPF of at least 15 and rated four or five stars. Remember to apply plenty of sunscreen and reapply regularly throughout the day. All sunscreens need to be reapplied after swimming.

Don't get caught out

It is easy to underestimate the strength of the UV rays in the UK, especially in coastal areas where the temperature is cooler. And remember that UV rays can still be strong on cloudy days.

Shield little ones

Take special care with babies and young children.

Donate today to help Cancer Research UK make more incredible strides forward in diagnosis, prevention and treatment of cancer. No matter how small or large, your gift will lead to dramatic changes to cancer outcomes in your lifetime.

For example:

£40 could pay for a cancer biopsy, where a tiny sample of someone’s tumour is taken for research

£250 could buy 500 plastic dishes, essential for scientists to grow and study cells in the lab

£1,000 could help fund a clinical trial of a new, more effective treatment for skin cancer

Join Cancer Research UK on its mission towards the day when all cancers are cured.

Advertiser content for

Advertisement feature for

THE FUTURE:

16,000 new cases

of melanoma

skin cancer

each year in the UK

40 years

Melanoma skin cancer survival in the UK has doubled in the last

Bowel cancer incidence is projected to fall by 11 per cent by 2035. Here are just a few examples of the work that’s going on to help achieve this, and to improve treatments for those who do develop the disease.

Smart immunotherapy

The next frontier in treatment is undoubtedly immunotherapy, explains Professor Sergio Quezada who is leading research at the UCL Cancer Institute. “We’re developing personalised T-cell therapies to target mutations only expressed by the tumour cells. We want to steer the immune response to make T-cells even more powerful to fight tumours,” he explains.

Understanding ROCK

The research into the make-up and activity of cancer cells is advancing with multiple projects across the UK. Professor Victoria Sanz-Moreno, based at Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London, has discovered how a molecule called ROCK helps cancer cells move and spread. “It may also affect the immune system,” says Sanz-Moreno, whose research has advanced the way in which we understand the biology of the disease. “It may be that using drugs to stop these molecules, alongside other drugs that interact with the immune system, is the best way to help patients whose melanoma has spread to other parts of the body.”

Precision medicine

Saving lives in our lifetime: Skin cancer

In this long read, we reveal how the connection between skin cancer and UV exposure was discovered and examine how harnessing our own immune system may hold the key to treating melanoma

JUMP TO

Timeline

Case Study

Symptoms

Prevention

Skin cancer is the abnormal, out-of-control development of cells within the skin. There are three main types, depending on which cells they affect within the outside layer of skin known as the epidermis: basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (both referred to as non-melanoma), and malignant melanoma skin cancer. Other types of non-melanoma do occur, but only rarely.

What is it?

Produced by Telegraph Media Group

Words Caroline Roberts Commissioning editor Jess Spiring

Sub editor Loveday Cuming Designer Sandra Hiralal

Digital developer Pedro Hernandez Picture editor Emma Copestake

Web producer Katherine Scott Project manager Alex Brooksbank

Advances in genetic sequencing have allowed researchers to develop new targeted cancer treatments. A team led by Professor Richard Marais at the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute are studying a molecule called BRAF, which is faulty in about 50 per cent of melanoma patients. They have worked out how BRAF’s activity is controlled by the cell, and now are trying to find out which molecules the faulty BRAF is joining forces with to cause cancer. They are also looking at why some skin cancers respond better to treatment than others, and are developing better ways to diagnose and monitor the disease. The team will use what they uncover about BRAF’s role in triggering cancer to develop new drugs that target this molecule, which can be tested in clinical trials.

Cancer Research UK recommends you tell your doctor if you have:

Diagram of skin

[Michael Stratton]

How Cancer Research UK plans to continue tackling skin cancer

Will you burn today?

The UV index indicates how strong the sun’s UV rays are and when we might be at risk of burning, depending on where you are. If the UV index is 3 or above, think about skin protection, especially if you burn easily. The UV Index measures the position of the sun, forecast cloud cover, and ozone amounts in the stratosphere. You can find it at metoffice.gov.uk/uv and on most weather forecasts.

There are

approximately

86%

In the UK

of melanoma skin cancer cases are preventable

Melanoma skin cancer makes up

5%

of the UK’s total cancer cases